Illustration: John Hersey

a conservative president who is deeply unpopular with Americans. A country facing profound economic and security challenges. New technologies upending old media. A cohort of new immigrants and a bulging generation of young people ready to transform the political calculus.

2008? No, 1932, the tail end of the Hoover administration. And you know how that one turned out. FDR and his fellow progressives took on the challenges of their day and built the domestic programs and international institutions that ushered in an era of unrivaled prosperity and stability. They used a new medium—radio—to reach citizens, and fashioned a new majority coalition from the emergent demographic realities of their time.

Today’s progressives face a political opportunity as great as any seen since. The election of 2006 may well have marked the end of the conservative ascendancy that began with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. George W. Bush now has the potential to do what Herbert Hoover did in the 1920s—tarnish his party’s brand for a generation or more.

As in FDR‘s day, a new media is emerging, one that will ultimately replace the broadcast model of the 20th century. A new American populace is emerging, led by the arrival of the millennial generation and a new wave of immigrants, particularly Hispanics. And once again, the nation faces massive challenges—from climate change to health care in the era of biotech and preparing young people for a global economy. On the eve of the 2008 election, it’s worth raising our sights beyond what it would take for a Democrat to win the presidency, and begin thinking about what it would take to bring about deeper, more lasting changes. The stars have aligned to give progressives a chance to permanently shift the conversation about the nation’s values. The question before us now is, Do today’s progressives have what it takes to do what FDR and his allies accomplished 75 years ago—seize the new politics, take on the big challenges, and usher in a new era?

in a way, the story begins with those fireside chats of FDR‘s. As the 20th century progressed, American politics became increasingly organized around broadcast media. But now top-down, one-to-many communication is giving way to a very different kind of media—diffuse, participatory, individualized. In 1980, more than 50 million people watched the network evening news on any given night; in 2005 the number was down to 27 million. By 2010, as many as half of all voters will have the ability to skip commercials thanks to TiVo and other digital video recorders. Last year, 100 million videos a day were being downloaded from YouTube, and its owner, Google, had $10 billion in ad revenues, surpassing cbs.

This is good news for progressives. The gop‘s success in old media—think Morning in America, Pat Robertson, Willie Horton, Rush Limbaugh, Swift Boat—was essential to its ascent, while the emergent blogosphere and social networking sites play to progressive strengths. (Finally, decentralization and lack of hierarchy are an asset rather than a liability.) And though TV will be around for some time, it is going through seismic change as video migrates to cable, satellite, the Internet, and cell phones—79 million Americans will have phones capable of handling video by 2009.

These technologies have revolutionized our lives in many ways, but one of the consequences is only beginning to be understood: As media become more participatory, so can politics. In the broadcast era, a presidential campaign consisted of quick stops on an airport tarmac (for local evening TV news coverage), 200 young people in a headquarters (largely to shepherd the candidate to more TV coverage), and a constant scramble for the perfect 30-second spot.

Howard Dean’s 2003 campaign was the first to put forth a truly 21st century, post-broadcast model—one that saw people as partners in the fight, not just as couch potatoes to be convinced or donors to be solicited. It took advantage of new tools—blogs, early online video, and the kind of voter databases that Republicans had mastered decades earlier. But most important, it put at its very core the notion that average people could be trusted to take action on behalf of the campaign.

Dean lost, but his campaign model survived—and today is becoming the new norm. This year, every one of the major Democratic candidates is running an Internet-oriented campaign, relying on the web for fundraising, organizing, and messaging. And even as the new tools are changing the way political insiders do business, they are also opening the system to new players: Organizations started by people with little or no experience in politics, such as MoveOn, Daily Kos, and ActBlue, are growing as powerful as the 20th century institutions that preceded them. Last year a 26-year-old Facebook user decided to rally support for Barack Obama. Within a month he had 278,000 supporters signed up. In 2003, it took Howard Dean six months to get a little more than half that many registered on his website.

This new paradigm represents a profound threat to the politics of privilege. Funding expensive broadcast campaigns forces political leaders to raise enormous sums of money, giving large corporations and wealthy individuals disproportionate influence. Republicans and Democrats have both played this game, but the Republicans consistently won; now, using Internet fundraising, Democratic Party committees consistently out-raise Republicans. The two leading Democratic presidential candidates raised $60 million in the second quarter of 2007—60 percent more than the $38 million for the two leading Republicans. By July, Barack Obama already had 258,000 donors to his campaign, more than any presidential campaign ever had at that point. Embracing this model has allowed the progressive movement and the Democratic Party to become much more authentic champions of the middle class, dependent as they now are on the financial support of average people.

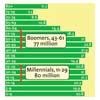

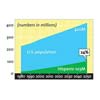

the other massive trend transforming politics is the changing composition of the electorate. Some shifts, such as the exodus to the sub- and exurbs, to the South and West, the aging of the baby boom generation, and the shift from industrial to a digital culture, have been much discussed. Others, like the emergence of the millennial generation, the boomer babies and young immigrants born from 1978 to 1996, are less well known. They number approximately 80 million, 3 million more than their parents’ generation, and we should expect to see them transform society, culture, media, and politics just as profoundly. They are the most diverse American generation ever, with nearly 40 percent from minority groups; chances are that within their lifetime, the term “majority” will become almost meaningless when applied to race.

Already, indications are that this generation is politically engaged, votes in high numbers, and leans overwhelmingly Democratic. In 2004, people age 29 and under would have given Kerry a landslide of 372 electoral votes had they been the only ones voting. In the 2006 congressional election, that same age group went for Democrats over Republicans by 22 percent—an almost unheard-of margin. Conventional wisdom has it that if a generation votes for one party in three consecutive elections, it tends to stay with that party for life. If that’s true, the stakes are high for 2008.

But the millennials’ impact will show up beyond the ballot box. Polling data indicate that they are unusually civic minded (they volunteer at the highest level recorded for youths in 40 years, according to one study) and hold a wide range of progressive values: Large numbers of them are concerned with the environment, support gay marriage, prefer a multilateral foreign policy, and even believe in government again. (Sixty-three percent think government should do more to solve the nation’s problems.) This generation is poised to become the core of a 21st century progressive coalition.

It’s the Demographics, Stupid

(Click here to show the demographic charts)

The other critical new constituency gets a lot of attention, but not often for its potential as a voting bloc. At 15 percent of the population, Hispanics are now the nation’s largest minority group and the fastest-growing part of the electorate. By 2050, one in four Americans will be of Hispanic origin. In the border states, Hispanics already make up 30 to 45 percent of the population—and between 10 and 30 percent of the voters—but their influence extends throughout the country. Two of the states with the fastest-growing Hispanic populations are Georgia and North Carolina.

Hispanics have traditionally thrown their support to Democrats, but between 1996 and 2004 the gop doubled its share of the Hispanic presidential vote to 40 percent. Then, in what may become known as one of the great strategic mistakes in American politics, conservatives waged a national campaign to demonize immigrants. In 2006 Hispanics went nearly 70 percent for Democrats, up from 58 percent for Kerry in 2004; their share of the electorate increased by 33 percent from 2002.

This could herald a national shift akin to what happened in California in the 1990s, when Republican governor Pete Wilson backed a harsh anti-immigrant referendum, pushing many Hispanics permanently into the Democratic camp and significantly increasing the number who voted. Partly as a result, California—the home of Nixon, Reagan, and the antitax revolt—is a reliably blue state run by a very progressive legislature, and its Republican governor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, has essentially become a progressive.

today these new demographic realities are creating an opening for progressives to craft the next great electoral strategy—one that has Democrats building on deepening strongholds in the Northeast and Pacific West, while bringing together enough progressive and progressive-leaning voters throughout the rest of the country to forge a real 21st century majority.

This new strategy, as scholar Thomas Schaller has noted, is essentially the long-overdue progressive response to the gop‘s Southern Strategy, which ripped the South from Democratic control and was critical to the right’s recent ascendancy. At its heart is the recognition that the South has gone from a core Democratic area—a position it held from the time of Thomas Jefferson—to a Republican-leaning, though competitive, region. Population growth along with changing party allegiances nationwide now allow Democrats to make up the ground lost in the South in other regions, confirming that, as Howard Dean has argued, Democrats need a 50-state approach.

The good news is that this new strategy is already yielding results. Forty-one states have either a Democratic governor or senator. The gop can only claim the same in 38 states. In 2006 the Senate fell to late wins in the red states of Montana and Virginia, and the House because of crucial victories in Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Indiana, North Carolina, and Ohio.

The ultimate test of any national electoral road map is whether it can deliver the White House—and this one finally looks like it may. Let’s start with the much underappreciated fact that Democrats in each of the last four presidential elections have won 248 of the 270 votes needed for victory by sustaining a lock on 15 states in the Northeast, Midwest, and West. The gop, meanwhile, has held 16 less-populous states, for a total of 135 votes, in each of these same four elections.

Add to this reliable Democratic base the heavily Hispanic states of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Nevada, and Florida (whose Hispanic population, incidentally, is no longer majority Cuban or majority Republican), all of which went for the Democratic presidential candidate in at least one of the last four elections and are now much more Democratic because of the epic shift in the Hispanic vote. Winning the four Southwestern states would put the party at 277 Electoral College votes—more than enough for victory. Adding Florida would put it at 304. If you throw in swing states where Democrats have scored impressive wins in recent years—Iowa, New Hampshire, Ohio, Virginia, maybe even Arkansas—Democrats could construct a durable majority of 354 electoral votes: landslide territory.

The new strategy takes the same regional approach that worked to win Congress, creating a strategic alignment among Senate, House, and presidential aspirants not seen among Democrats in a long time. But it also does something else that is critical: By freeing Democrats from the need to win significant victories in the nation’s most conservative places, it will allow progressives to be progressive, to avoid some of the brutal ideological battles that can cripple a movement, and most important, to take risks and think big.

but politics is not an end in itself; what counts is what you do with the power once you have it. Democrats, from the new Congress to the presidential field, are in the early—emphasis early—stages of creating a new approach not just to strategy and tactics, but to governing as well. All the Democratic hopefuls are talking about dramatic changes—some suggest “transformational” shifts—for health care, immigration, energy, and national security. And Congress has at least begun the laborious process of orienting governance away from the myopia of the Bush era, with steps like raising the minimum wage and passing new ethics rules while launching formal discussions about globalization and climate change.

But pushing through the changes that made up the New Deal and the Great Society required big ideas—and also big majorities, the kind that often need to be built over time. Here too there is reason for optimism. Going into this election, the Democrats have the wind at their backs; polls find that voters prefer a Democratic president by a 12- to 24-point margin, a gap bigger than at any time since Watergate. Dems picked up 31 House seats, 6 governorships, and 6 Senate seats, plus more than 300 statehouse seats across the nation in 2006. If the Democratic advantage holds for this coming election, there is a chance to not only solidify those gains, but expand on them, especially via an unusual opening in the Senate, where no fewer than 21 Republicans are up compared to only 12 Democrats. This presents a chance to significantly improve on the current 1-vote margin—toward the magic 60 that can break filibusters?

Ultimately, a real movement would achieve something broader than just an electoral majority—a permanent shift in the ideological orientation of the country. Before the New Deal, more than 50 percent of the elderly lived in poverty. Social Security changed that, and despite talk of privatization, eliminating it altogether is off the table. The political and societal changes of the ’60s couldn’t be rolled back either: Nixon expanded the Great Society and even launched the Environmental Protection Agency.

There’s a progressive strain of Republicanism that reaches back to Teddy Roosevelt and to Abraham Lincoln before him. It has been recessive for the last quarter century, but with the right sequence of events could express itself once more. Already there are some early signs: Arnold Schwarzenegger in California and New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, who recently relabeled himself an independent. Goodbye gridlock—hello bipartisan cooperation?

at the time of his election in 1932, FDR had offered very few concrete ideas on what his administration would do about the collapsing economy that he faced. However, he more than made up for that with entrepreneurial panache. In the famous first 100 days after his inaugural, he pulled together a “brain trust” of experts from many fields and had them hammer out practical solutions, drawing on decades of progressive thinking and borrowing from many political ideologies—from socialists all the way to his Republican antagonists. They adopted a routine of constant, rapid trial and error, with a clear bias toward what worked.

With time, the country stabilized and the New Deal took shape. With the Depression vanquished, President Roosevelt went on to become the global leader who shook hands with Churchill and Stalin at Yalta and helped reshape the world’s political and economic architecture, laying the foundation for what would become the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the Bretton Woods Accord on global currencies. And progressive innovation did not stop with FDR: From the GI Bill to the Peace Corps to Medicare, from the labor movement to civil and women’s rights, it continued for the better part of a century, transforming America and the world.

FDR and his cohorts mastered the new politics of their time: used the new tools, built a new coalition, created a new agenda. They developed a grand strategy to take on the challenges of the moment, and built the foundation for a long era of progressive dominance.

The time is right for 21st century progressives to do the same. Our moment may be analogous to 1932, or it might be closer to 1900, the start of the classic Progressive Era that brought us women’s suffrage and the income tax. In either case, we need to think about the current opportunity not just as the span of one presidency, but as the possible beginning of an era measured in decades. That’s what it will take to begin to deal with the planet’s changing climate, restore America’s standing in the world, raise people out of global poverty, stabilize a shifting global economic order, incorporate the best and mitigate the worst of biotech, and so much more that needs to be done.

This is not any old moment in history. It has the potential to definitively mark the end of a conservative period and the start of a progressive one. It’s not inevitable. It will take real leadership on many fronts for many years to come. But for the first time in a very long while, it’s truly possible.

We’ve done it before. We can do it again. Let the new progressive era begin.

Kids Today: Millennials on Government, Gays, And Getting Ahead

|

GENERAL |

YOUTH |

ISSUE |

|---|---|---|

|

37% |

56% (18-29) |

support gay marriage |

|

77% |

95% (18-29) |

approve of interracial relationships |

|

58% |

32% (18-25) |

agree that the federal government “is usually inefficient and wasteful” |

|

52% |

40% (18-25) |

say regulating business “does more harm than good” |

|

38% |

52% (18-25) |

agree that corporations “generally strike a fair balance between profits and private interest” |

|

62% |

81% (18-25) |

say their generation’s most important goal in life is to get rich |

|

49% |

68% (18-24) |

say protecting the environment is at least as important as protecting jobs |

|

47% |

62% (17-29) |

favor tax-financed, government-administered universal health care |

|

38% |

52% (18-25) |

think immigrants “strengthen the country with their hard work and talents” |

|

58% |

74% (18-29) |

say “people’s will” should have more influence on U.S. laws than the Bible |

|

41% |

29% (18-25) |

say overwhelming force is the best way to defeat terrorism |

|

18% |

26% (18-25) |

describe selves as “liberal” |

|

62% |

42% (18-25) |

say “I feel it’s my duty as a citizen to always vote” |

Compiled by Jen Phillips. Sources: motherjones.com/50-year-strategy.