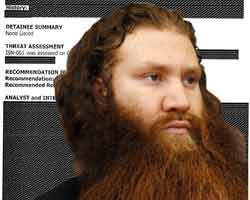

Murat Kurnaz, a young Turkish citizen born and raised in Germany, traveled to Pakistan to learn more about Islam in October 2001, weeks after the September 11 terrorist attacks against the United States. In short order, arrested and held by US forces in Kandahar, and then shipped off to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Bad timing was his only crime. (See here for MoJo’s coverage of Kurnaz’s plight, based on interviews with German intelligence officials and exclusive documents. See here for a timeline of Kurnaz’s Kafkaesque odyssey.)

Murat Kurnaz, a young Turkish citizen born and raised in Germany, traveled to Pakistan to learn more about Islam in October 2001, weeks after the September 11 terrorist attacks against the United States. In short order, arrested and held by US forces in Kandahar, and then shipped off to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Bad timing was his only crime. (See here for MoJo’s coverage of Kurnaz’s plight, based on interviews with German intelligence officials and exclusive documents. See here for a timeline of Kurnaz’s Kafkaesque odyssey.)

By 2002, according to documents obtained by his attorneys, both the US and German governments had determined conclusively that Kurnaz was neither a terrorist, nor a terrorist sympathizer or supporter, but American military officials nonetheless refused to release him and instead held him in solitary confinement for five years. For much of that time, he was unaware that anybody in his family knew where he was or if he was alive. And for the entire stretch he was subjected to torture.

In his account before the House Foreign Affairs’ Oversight Subcommittee on Tuesday, Kurnaz detailed a technique visited upon him in Kandahar called “water treatment”—a perverse twist on a more widely known technique called waterboarding—wherein the victim’s head is forced into a bucket of water while he’s punched repeatedly in the stomach, causing him to inhale water.

Additionally, he said, he was subjected to religious and sexual humiliation, administered unknown drugs against his will, and electrocuted via wires attached to his feet.

In a bitter irony, Kurnaz’s innocence became the rationale for his continued incarceration. He was told repeatedly that he’d be held forever unless he signed a statement admitting his role in a suicide bombing that was alleged to have happened in 2003. Kurnaz was, of course, in prison in 2003, and the suicide bombing he supposedly helped to orchestrate turned out to be a fiction.

“America’s adherence to the rule of law… and American values [have been] ignored. The treatment of these detainees—both in Gitmo and elsewhere—has been appalling,” said William Delahunt, the subcommittee chairman.

The two committee Republicans to attend the hearing were sympathetic to Kurnaz’s plight, but ranking member Dana Rohrbacher remained incredulous that the treatment he faced was anything other than an aberration. “I don’t believe it,” Rohrbacher intoned, suggesting that torture is not part of the military’s detainee treatment policy. To support his contention, Rohrbacher noted that none of the congressmen who have visited Guantanamo—Democrat or Republican—has returned with any evidence that torture is a systemic problem.

Rep. Jerrold Nadler, who sits on the House Judiciary committee scolded Rohrbacher, noting that American politicians are not allowed access to prisoners when they visit the installation, and have no other way of ascertaining how endemic the torture problem really is.

Rohrbacher’s disbelief also flies in the face of scores of media and watchdog reports, which show that prisoner abuse has been a matter of policy at Guantanamo and other U.S.-operated facilities around the world for years. And on the same day as the hearing, the FBI’s inspector general released a report praising the Bureau for not participating in the abusive interrogations conducted by other agencies—a direct insinuation that other agencies do indeed torture prisoners.

For his part, Kurnaz says stories like his are common among the prisoners who’ve been held at Guantanamo, 250 of whom remain in captivity. “Often people were released because their countries demanded it,” he said. “Others remain because their countries do not.”