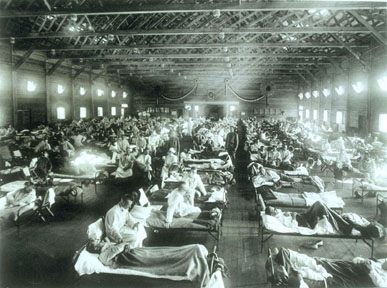

A new study in Emerging Infectious Diseases concludes that bacteria not influenza killed most people in the 1918 flu epidemic. The lesson: stock up on antibiotics for the next flu pandemic—bird flu, horse flu, or otherwise.

A new study in Emerging Infectious Diseases concludes that bacteria not influenza killed most people in the 1918 flu epidemic. The lesson: stock up on antibiotics for the next flu pandemic—bird flu, horse flu, or otherwise.

New Scientist reports that researchers sifted through first-hand accounts, medical records, and infection patterns from 1918 and 1919.

They found that bacterial pneumonia piggybacked on surprisingly mild flu cases. And the victims didn’t die fast. A supervirus would have likely killed them in three days.

Instead, most people lasted more than a week and some survived two weeks—classic hallmarks of pneumonia.

Most compelling: medical experts of the day identified pneumonia as the cause of most of the 100 million deaths—the most lethal natural event in recent human history.

Other research suggests the brutal mechanism. Influenza killed cells in the respiratory tract, which became food and home for invading bacteria that overwhelmed overstressed immune systems.

Ten years later, penicillin overpowered bacteria in subsequent influenza epidemics. But nowadays we’re having those nagging antibiotic problems.

So health authorities are increasingly interested in the role bacteria will likely play in the next pandemic. Yet little action has been taken. “They are just starting to get to the recognition stage,” says Jonathan McCullers, infectious disease expert. “There’s this collective amnesia about 1918.”

Julia Whitty is Mother Jones’ environmental correspondent, lecturer, and 2008 winner of the Kiriyama Prize and the John Burroughs Medal Award.