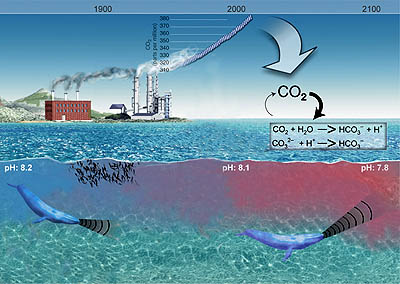

Increasing atmospheric CO2 increases the acidity of seawater, which allows sounds, like whale calls, to travel farther.

Image: (c) 2008 MBARI (Base image courtesy of David Fierstein)

The acidification of seawater due to absorption of atmospheric CO2 is also enabling sound waves to travel farther. That’s bad news for marine life, including whales and dolphins, who rely on sound for hunting and communication and who are already stressed by noisy ship traffic and military sonar.

A team from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute predicts that underwater sounds will travel up to 70 percent farther in some areas in 2050 than they do today. Whales could be heavily impacted. Military sonar already disrupt whale behavior more than 300 miles away. Dolphins and fish that use sound to locate prey, to avoid predators, and to defend their territories, will also be affected.

Think of it as our world suddenly getting way, way brighter, blindingly bright, with no sunglasses anywhere. The study, published in Geophysical Research Letters, used IPCC projections that ocean pH will drop by 0.3 units by 2050—four times faster than the the past 250 years. The researchers also conducted field and lab experiments testing sound conductivity while estimating increases in ocean temperature and reductions in oxygen content, conditions also affecting underwater acoustics.

Julia Whitty is Mother Jones’ environmental correspondent, lecturer, and 2008 winner of the Kiriyama Prize and the John Burroughs Medal Award.