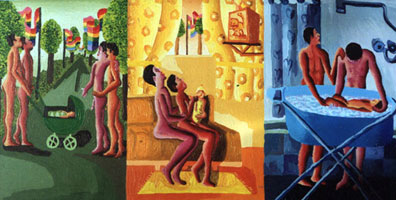

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

What’s Loving v. Virginia all about? Or Romer v. Evans? During last week’s closing arguments in the closely-watched legal challenge to California’s Prop. 8, attorney Ted Olson referenced these and a string of other US Supreme Court rulings in support of same-sex marriage. SCOTUS will most likely cite these same cases in determining the (un)constitutionality of Prop. 8 and other state laws banning gay marriage. Here’s a quick breakdown of these and other cases that challenged some popular yet discriminatory laws.

Loving v. Virginia

In 1958, Mildred Jeter and Richard Loving, an interracial couple that married in Washington DC, were arrested when they returned home to Virginia. Their crime: violating the state’s ban on interracial marriage. Their one-year jail sentence was suspended on the condition that they leave the state and not return for 25 years. The Lovings left, but took their case to multiple courts, including Virginia’s Supreme Court of Appeals (now called the Virginia Court of Appeals), which ruled in favor of the state’s right to ban and penalize interracial marriages. In 1967, SCOTUS overturned the decision, ruling that the interracial marriage ban violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s protection of individual liberties.

Wait. Why couldn’t they get married?

The law’s supporters said it was “God’s will” that people of different races not be married—which sounds familiar. At the Lovings trial, a judge actually said: “Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.”

What’s this got to do with gay marriage?

Swap gender for race, and the injustice is evident. SCOTUS also noted that “the freedom to marry has long been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.” (My emphasis.) Nowhere in the ruling does it say, “This applies only to heterosexuals.”

Romer v. Evans

In 1992, Colorado voters barred state and local governments from protecting people’s civil rights based on their sexual orientation. But SCOTUS ruled that this voter-approved amendment to the state constitution sneakily violated the Fourteenth Amendment, which promises that no person shall be denied equal protection under the laws.

What’s it got to do with gay marriage?

Prop. 8 denies people’s civil rights based on sexual orientation.

Lawrence v. Texas

In 1998, Houston police officers entered John Lawrence’s apartment after gettting a disturbance call from his neighbor, and found him having sex with another man—a crime in Texas. The men were arrested and convicted of “deviate sexual intercourse.” Five years later, SCOTUS overturned this state’s anti-sodomy law.

What’s this got to do with gay marriage?

From the Supreme Court’s ruling (emphasis added): “Our laws and our tradition afford constitutional protection to personal decisions relating to marriage, procreation, contraception, family relationship, child rearing, and education. Persons in a homosexual relationship may seek autonomy for these purposes just as heterosexual persons do.” As Olson argued last week, Prop. 8 “takes away the fundamental right to marry from a class of persons based upon their practice of something that’s been decided to be a fundamental constitutional right of liberty, privacy, association.”

Sweatt v. Painter

Heman Marion Sweatt was denied admission to the University of Texas Law School, the Supreme Court noted, “solely because he is a Negro and state law forbids the admission of Negroes to that Law School.” During the trial, Texas created a separate law school for blacks and offered Sweatt admission, but we all know how the “separate-but-equal” thing played out. In 1950, SCOTUS ruled in Sweatt’s favor, again based on the Fourteenth Amendment.

What’s this got to do with gay marriage?

Separate ain’t equal. And domestic partnerships aren’t equal (PDF) to marriage.

So there you have it folks. True, California voters approved Prop. 8. But if a public poll were taken in the 1800s, or even the 1950s, to decide the fate of interracial marriage, an unjust outcome would have been predictable, too.