[For more on the WikiLeaks Afghan document dump, read posts by Kevin Drum here and Adam Weinstein here.]

WikiLeaks is making headlines again with the release of an enormous trove of secret US military documents from Afghanistan. The Afghan War Diary, as WikiLeaks has dubbed it, was first given to the New York Times, The Guardian, and Der Spiegel, which have vetted, analyzed, and packaged the 92,000 documents into what amounts to the biggest story about the war since Osama bin Laden slipped away. As Kevin Drum explains, the stories don’t seem to have many major surprises (besides the Taliban’s use of Stinger missiles) for anyone who’s been paying attention: “the basic picture is basically the one we’ve known for a long time: a difficult, chaotic battlefield that’s shown little progress since the very beginning of the war.” But considering that most Americans—and most American lawmakers—haven’t really been paying attention to Afghanistan, this could prove to be the watershed moment after which no one can honestly claim ignorance of what’s really happening over there.

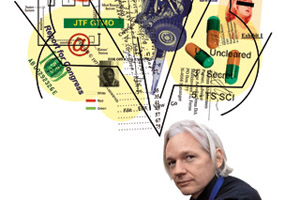

If the Afghan leaks become the next Pentagon Papers, it would be a much sought-after feather in the hat of WikiLeaks and Julian Assange, its shadowy, image-conscious mastermind. And it could mark the beginning of a new chapter for the organization, which has gone through some strange growing pains since it leaked its “Collateral Murder” video in April. That leak marked the first time that WikiLeaks, and Assange in particular, had assumed an active role in analyzing and promoting its own material—a decision that brought it more attention while opening it up to criticism that it had strayed from its original “just the leaks, ma’am” approach. The subsequent arrest of the alleged leaker of that video spawned a series of hyperbolic rumors about Assange being on the run from American intelligence and claims that WikiLeaks was sitting on thousands of leaked State Department cables, spawning competing volleys of mis- and disinformation that mostly served to burnish WikiLeaks’ mystique. In the meantime, WikiLeaks seemed busier tweeting its own horn and swatting down foes than keeping the leaks coming.

So it’s a bit unexpected to see WikLeaks emerge from the rabbit hole of intrigue to assume the the role of a fairly traditional source, stepping back and (so far) letting mainstream journalists do the analysis and presentation of its Afghan docs. It’s an interesting decision for many reasons, not least of which is the possibility that WikiLeaks may have found the perfect way to balance its remarkable ability to obtain sensitive information with its paradoxically opaque M.O. But perhaps the approach is purely pragmatic: Spend some time with the raw data in the Afghan War Diary, and you’ll probably soon want someone else to do the heavy lifting of translation, aggregation, and explanation. (As MoJo‘s Adam Weinstein, who’s spent some time with the type of classified docs released here, writes, “most of this information is tactical nuts and bolts, devoid of context, and largely useless for a war narrative.”)

There’s still plenty of questions surrounding the Afghan leak. In the weeks following the release of “Collateral Murder,” WikiLeaks said it was on the verge of releasing similarly graphic footage of an airstrike in Afghanistant that had killed scores of civilians. It hasn’t done so yet, and it’s unclear if that video is connected to this leak. It’s also unclear whether Bradley Manning, the US Army intelligence analyst who’s been accused of leaking the Iraq video, also leaked the Afghan docs. And there’s still the enigma of what the heck Assange was referring to a month ago when he said the subject of his next project was analgous to “mass spying that had affected many, many people and organisations.” Maybe that’s a leak for another day, and maybe it’s one he’s keeping just for WikiLeaks.