Flickr/<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/tylerhowarth/2231251437/" target="_blank">Tyler Howarth</a>

At one of my first jobs ever, there was a guy who would print out every single email he received. Then, to make matters worse, he would forget about his printed emails and leave them on the printer. Occasionally, just to give him a hard time, we would hand deliver his emails to him and announce their contents. “Your wife says pork chops for dinner and she loves you!”

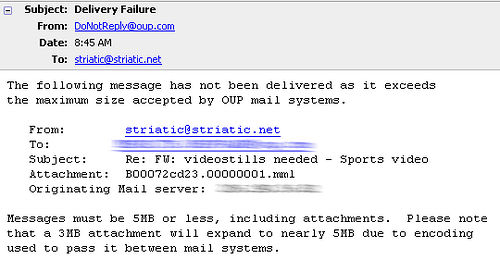

I haven’t encountered anyone with that irksome habit since, probably because most people now understand that printing something doesn’t make it more real. But according to Matthew Yeager, a data storage expert who works for the UK data services and solutions company Computacenter, emails—especially those with attachments—still use energy and create greenhouse gas emissions, even if you don’t print them. Last month, Yeager told the BBC that sending an email attachment of 4.7 megabytes—the equivalent of about 4 photos taken on a point-and-shoot digital camera—creates as much greenhouse gas as boiling your tea kettle 17.5 times. I called Yeager to find out the whole story.

What I ended up getting was a very brief introduction to the strange world of data storage. According to Yeager, at some point in the coming year, the world will have a grand total of 1.2 zettabytes of stored data, requiring equipment with a mass equivalent to that of 20 percent of the island of Manhattan. Wonder how much data 1.2 zettabytes actually is? “If you took all the content in all the US’s academic libraries and multiplied it by half a million, that would be 1.2 zettabytes,” says Yeager.*

Part of the reason we have so much data has to do with redundancy: Let’s say you take a picture and send it to 20 people. Each of those people then have to download it, which requires equipment—personal computers, servers, and storage centers. Steve Duplessie, a senior analyst at the Massachusetts-based data storage company Enterprise Strategy Group, explained it this way. “Ten years ago, a movie studio would physically make a certain amount of copies and then ship them off to the movie theater. Today every kid you know can create the equivalent amount of data in two minutes with an iPhone. We keep making data easier to create, so people do it. And data is not sedentary. It is shipped everywhere, usually over email. All of a sudden there are 7,000 copies, and because of that there are 7,000 devices that are being run to support that data.”

Yeager didn’t go into the details of how he arrived at the 17.5 kettle-boils figure, and Duplessie told me he wonders how anyone could come up with a data-storage figure that precise. Still, Duplessie says, the important lesson is, “Data is physical. When you have a million copies of the same thing, that’s a big problem.”

The good news is that we are getting better at sharing data more efficiently. Many email programs are beginning to make use of a concept called virtualization, or spreading the workload of transmitting data across many different servers, thereby making the whole process more efficient. “Virtualization is like the carpool lane,” says Yeager. “Your email is carpooling. The more people you stick in that car the better.” Equipment is getting more efficient, too. According to Yeager, the newest servers are about 1/20th the size of old servers, and as many as 50 times more powerful. Yeager notes that a few email servers—for example, Google—have already made these improvements (meaning that if you’re a Gmail user, you’re probably doing significantly better than the 17.5 boils figure).

The bottom line: Avoid sending giant attachments if you can. “In the last five or ten years a lot of people have added these ‘think before you print’ signatures to their emails,” says Yeager. “Well we should all have ‘think before you attach.'” Luckily, there are easy ways to share your data without attachments: Instead of sending photos directly to all your friends and family members, upload them to central locations like Flickr or Facebook. “It’s much more efficient to send a link to a place where everything is stored,” says Yeager. For audio and video files, I often use hosting sites like Sendspace or MediaFire.

*- This sentence originally misquoted Matthew Yeager that 1.2 zettabytes was equal to the data in all the world’s academic libraries multiplied by half a million. 1.2 zettabytes is actually only equal to the data in all the US’s academic libraries multiplied by half a million.