Two questions: How much do you spend each month on rent or a mortgage payment? And how much do you spend each month on transportation?

Chances are you can answer the first question instantly. But the second? Hmm … Transportation costs are trickier, since you don’t pay them all at once or all to the same place, and they can vary month to month. But they’re a significant expense for most households, and a seriously overlooked one.

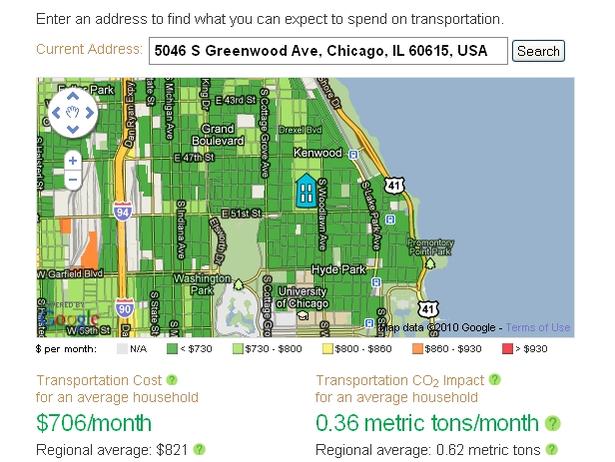

Chicago’s Center for Neighborhood Technology offers an easy way to get a rough estimate with Abogo, a new website that measures what an average household in a neighborhood spends on getting around—including car ownership, car use, and transit use. Plug in an address and the site brings up a color-coded map. For example, Barack and Michelle Obama’s old block in Chicago’s Kenwood neighborhood has an average transportation cost of $706 a month, compared with $821 for the metro region. abogo.cnt.org

abogo.cnt.org

The site draws on nine data sets, mostly from the US census, that include density, average commute time, commuters per household, and a transit connectivity index. It also calculates greenhouse-gas emissions from transportation—Kenwood residents average 0.36 metric tons per month, about half the metro average.

CNT’s hope is that the information nudges homebuyers and renters toward more compact, walkable places—or at least gives them a more realistic picture of what it costs to live in auto-dependent neighborhoods.

“When you choose a home, you’re choosing a location and everything that has to do with that location,” said Stefanie Shull, a CNT policy analyst. “That location determines how much you’re going to have to drive to take care of your daily needs.” The Atlanta area is a sea of high-transport-cost red.

The Atlanta area is a sea of high-transport-cost red.

Abogo—the word is a combination of “abode” and “go”—is a consumer-facing extension of CNT’s Housing + Affordability Index, which tries to inject transportation costs into discussions about housing.

For years the standard rule of thumb, validated by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, has held that housing is affordable if it costs 30 percent or less of a family’s income. There are obvious flaws with this method (Roger Valdez at Sightline has a good overview). For one, 30 percent for a family making $20,000 leaves far less to spend on groceries, clothes, day care, and whatnot than 30 percent for a family making $100,000. From an environmental standpoint, the 30-percent rule misses two important expenses: home energy use (more on that in a post soon) and transportation.

CNT’s index takes a more holistic approach, proposing that housing and transportation costs together shouldn’t exceed 45 percent of a family’s monthly income.

By that standard, the nation’s “affordable” housing pool is a lot smaller than previously assumed. When CNT analyzed 337 metro areas that include 80 percent of the nation’s population, it found that 69 percent of neighborhoods are considered affordable under the conventional definition. But just 39 percent are affordable under the 45 percent H+T standard. Concentric rings of higher costs surround Houston.

Concentric rings of higher costs surround Houston.

Not surprisingly, “drive to qualify” outer-ring suburbs accounted for much for the housing with higher-than-average transportation costs. CNT President Scott Bernstein suggested the gas-price surge in summer 2008 contributed to higher foreclosure rates in those areas. (Research sponsored by NRDC reached similar conclusions.)

“I’m not saying transportation costs caused the foreclosure crisis. I’m saying that once the economic crisis happened, people with higher transportation costs were more exposed,” Bernstein said.

Putting it to work

Mortgages that reward “location efficiency” are one promising but unproven tool that would use the H+T index to encourage people to buy homes in walkable, transit-oriented areas. CNT sees broader ways policymakers could use the index in evaluating housing, road, transit, and economic-development projects.

The big goal is convincing HUD, with its $47 billion annual budget, to redefine housing affordability to include transportation spending, says CNT’s Shull.

HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan has expressed support for the idea. “For the first time in the history of federal grant competitions, I want to announce today that HUD will be using location efficiency to score our grant applications,” he said at the Congress for the New Urbanism in Atlanta this spring.

But the department hasn’t made an across-the-board change. It’s starting by considering location efficiency for $140 million in funding it will make available largely through the Partnership for Sustainable Communities, a joint project with the Department of Transportation and the EPA. But even with that, it’s not clear how much location counts for compared to other factors.

“We’re not privy to what those formulas are,” said Shull. “We’d love to know how much weight they give this.”

Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.), chair of the Livable Communities Task Force, has introduced a bill that would require HUD to use the H+T index in all its grant scoring. And last month, Illinois Gov. Pat Quinn (D) signed a law directing state planning agencies to do the same.

Those small steps are encouraging, but John McIlwain, senior fellow for housing at the Urban Land Institute, suggests that shifting consumer preferences toward walkable urbanism will have a bigger effect. And Abogo can help those buyers and renters make better-informed decisions.

“I think it’s less a policy change and more a market change,” he said. “It’s about educating people that there are these tradeoffs, and what you’re looking for is not the cost of the house but the cost of the place.

“You’re going to find more and more people who want to live closer in. They know it’s more expensive to buy a house closer in. But when they do the total calculation they realize it’s going to be pretty much the same.”

This post was produced by Grist for the Climate Desk collaboration.