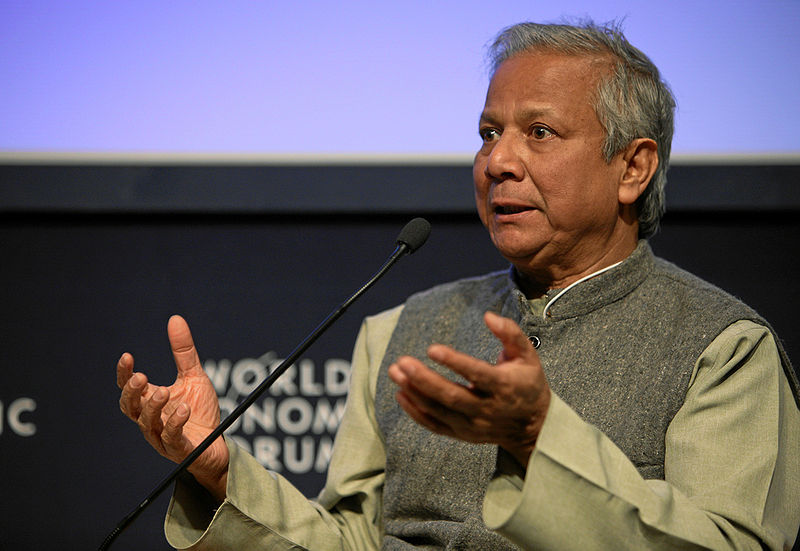

On Tuesday, Nobel Laureate Muhammed Yunus was deposed as managing director of the microcredit organization he founded 30 years ago, Grameen Bank. The reason? Bangladesh courts say the 70-year-old is too old. Yunus is now in violation of a national mandate that all citizens retire at age 60. Grameen Bank insists the issue was resolved a decade ago, when a then-59-year-old Yunus received government permission to continue [PDF].

Yunus’s removal comes just a few days prior to the English-language premier of a Danish documentary, Caught in Micro Debt, (Micro Debt in the English version), which takes aim at Yunus and Grameen. The film, which debuts in London today, is directed and produced by Tom Heinemann and has a different take on the man who has long been hailed South Asia’s savior to the poor. Indeed, Yunus has been so highly lauded by prominent people like the Clintons, President Obama, and Bono (not to mention Western humanitarian circles) that it’s only surprising a backlash to Yunus’ empire didn’t come sooner.

Heinemann—an independent, investigative journalist—interviewed scholars, humanitarians, a Grameen executive, and micro-borrowers in Bangladesh, India, and Mexico. Of the lendees who made the cut, only one debtor claimed success through Yunus’s program. The other accounts range from uncomfortable to downright horrifying. One debtor’s financial woes are compounded by a sick daughter, while another reports being bullied by hostile members of his borrowing circle (Grameen requires members borrow in groups, rather than individually). There are tales of threatening debt-collectors, usury as standard procedure, and, in one instance, a lendee’s spouse commits suicide because they cannot pay the money back.

Besides accusing Grameen of driving debtors to their graves, the documentary accuses Yunus of funneling Norwegian aid money into a partner company—which I wrote about back in December— accusations for which Yunus and Grameen have been exonerated by the Norwegian government.

David Roodman, a leading micro-finance academic, has been cautious in his response to Micro Debt, which he was interviewed for. In his Microfinance blog, he complains that:

Tom seems to have made pretty much the most negative movie he could. As I show just below, the film sensationalizes matters that have more to do with making Muhammad Yunus look bad than whether microcredit is good for the poor; exaggerates the Grameen Bank’s interest rates despite my explanations in e-mail to Tom and on this blog; and heavily favors negative voices, depriving viewers of the opportunity to glimpse the complexities of the real world and think for themselves.

While Roodman asserts personally that Heinemann tweaked interest rates to suit the film’s purposes, there are other examples as well. Two MIT economists, Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, write that in the rural Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, two-thirds of the poor have loans on which they pay an average 57% in interest. This number makes Yunus’s 17 to 24 percent interest (Roodman’s calculations) seem much more reasonable.

Banerjee and Duflo argue that “the simple fact that MFI (microfinance) lending has reached its current scale is a remarkable achievement. There are very few other programs targeted at the poor that have managed to reach so many people.” They go on to say that the structure itself is faulted and not entirely dependable as a stepping-stone to a perfect solution for the very poor.

Heinemann only touches the surface of how Yunus’s microfinace programs actually work— much-needed context crucial to a well-informed dialogue, or a documentary film that focuses on how microcredit fails the poor. And as Heinemann doesn’t always explain why exactly the lenders he interviews defaulted on their loans, the viewer is left to imagine how they got into their dire predicaments.

Local governments are taking steps to institute solutions. Government officials in Andhra Pradesh, where local women hold about 30% of the world’s micro-debt, tightened regulations after a series of suicides by lendees. And since the beginning of the year, other Indian states are planning to follow suit.

Heinemann doesn’t offer such a solution. He offers a look at the downside of microfinance, and trashes Yunus and Grameen, but doesn’t give us a convincing reason to sack the entire system. It’s certainly true that the failures of microfinance should be told; and a Nobel Prize isn’t an exemption from accountability. However, a documentary that prompts questions rather than merely emotions can act as a spark for a meaningful conversation.