Dan Herrick/ZumaPressAs a service to our readers, every day we are delivering a classic moment from the political life of Newt Gingrich—until he either clinches the nomination or bows out.

Dan Herrick/ZumaPressAs a service to our readers, every day we are delivering a classic moment from the political life of Newt Gingrich—until he either clinches the nomination or bows out.

After being sworn in as Speaker of the House in 1995 on a promise to tear down the welfare state, Newt Gingrich needed just one day to propose a new, $40 billion entitlement program to allow poor Americans to buy laptops. As he told the House Ways and Means Committee:

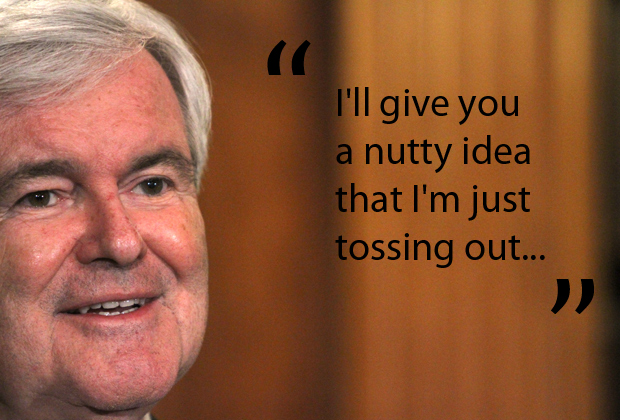

I’ll give you a nutty idea that I’m just tossing out because I want to start getting you to think beyond the norm. Maybe we need a tax credit for the poorest Americans to buy a laptop. Now, maybe that’s wrong, maybe it’s expensive, maybe we can’t do it. But I’ll tell you, any signal we can send to the poorest Americans that says “We’re going into the 21st century, third-wave information age, and so are you, and we want to carry you with us,” begins to change the game.

It was not the first time he’d floated the concept. Elizabeth Drew reported that Gingrich had “made a similar proposal several years [earlier], to an executive of a major technology company, and had been told it wasn’t feasible.” And in his 1984 book Window of Opportunity, Gingrich had heralded France’s move to put a telephone in every house as “an investment in the future and one which may make France the leading information-processing society in the world by the end of the century.”

Because poor Americans don’t pay income taxes, though, the tax credit wouldn’t do much good—unless it was a refundable tax credit, in which case it would basically be an entitlement by another name. (It was also a bit incongruous to propose giving away laptops while simultaneously trying to eliminate food stamps, but we all have our indiosyncrasies.) The Speaker backtracked shortly thereafter. As Michael Kinsley put it in the New Yorker:

Gingrich conceded that the laptop tax-credit idea was not merely “nutty” but “dumb” and added, “I shouldn’t have said it.” He even revealed that he had called up George Will to apologize—apparently what one does in such circumstances—though he did not reveal whether Will had given him absolution.