Women protest Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's regime.Freedom House/Flikr

Earlier this week, the US advocacy group Women Under Siege launched an open-source crowdmapping site that tracks incidents of sexual violence in the ongoing conflict. Since the anti-regime uprising began a year ago, rape has been a common tactic used by Syrian forces against the opposition. But sexual violence in Syria largely remains an underreported topic, and the project—funded by the New York-based Women’s Media Center—hopes to change that.

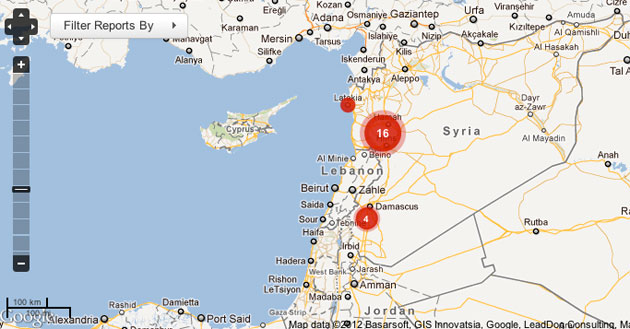

The site’s map enables users to record locations where they or someone they know was raped—becoming a real-time sexual crime tracker. The platform is notable since it gives victims and witnesses a means to anonymously report assaults with a simple tweet (#RapeInSyria), text, email, or comment on the site. Lauren Wolfe, director of Women Under Siege, hopes the map will point her team to the areas where survivor services are needed most. And once the security situation on the ground becomes more stable, she says, the group will work with researchers to verify the reports and build a database of evidence to hopefully pursue war crimes charges.

Still, there are kinks to be worked out. “The difficulty rests in people coming forward in the first place,” says Wolfe. “There are so many reasons for them not to say anything.” Her team is still building up multiple layers of precautions, like constructing a secure server and SMS number, so women don’t have to fear shame or retribution.

To preserve victim anonymity in a heavily repressed country like Syria, the group will have to roll out the map carefully, Wolfe says. As a result, she adds, the group isn’t yet promoting the site to the Syrian general public or soliciting reports from inside the country. The project is instead relying on media sources and refugee communities in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey to populate the site. The group is also working with Syrian human rights activists to get the word out to first responders. At present the site has about 20 reports, categorized by location, type of assault, and whether or not the perpetrators were government forces.

Similar crowdsourced maps in the last year or so have successfully gained traction: SyriaTracker, which charts human rights violations unrelated to sexual violence, has received over 1,500 reports since it launched last April; HarassMap, started in December 2010, records and responds to sexual harassment in Egypt (where military violence against women has been on the rise) and has logged over 600 cases.

Challenges aside, Wolfe says the effort to track rape during a conflict, as opposed to years after it ends, is a new phenomenon worth applauding. “We so often have to gather this information after the fact, after so much of it is lost, so anything we can do to get this information out can only help women.”