<a href="http://www.examiner.com/article/mitt-romney-will-win-the-presidency-with-275-electoral-votes?cid=PROD-redesign-right-next" target="_blank">Unskewed polls Dean Chambers predicts the outcome of the 2012 election.</a>

On Election Night, I tweeted that Republicans shocked about Mitt Romney’s loss Tuesday should be angry at a conservative media that misled them about the former Massachusetts’ governor’s chances.

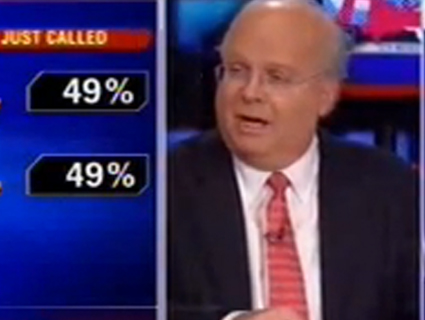

In the waning days of the race, much of this manifested in raising doubts about the polls and comical exaggerations about the possibility of a Romney landslide. Rush Limbaugh told his millions of listeners that “everything except the polls points to a Romney landslide,” but the problem went beyond mavens like Limbaugh to afflict more well-regarded political analysts like Michael Barone and George Will. The Weekly Standard‘s Jay Cost wrote, “I am not willing to take polls at face value anymore. I am more interested in connecting the polls to history and the long-run structure of American politics, and when I do that I see a Romney victory.” Analysts like Karl Rove—who through his stewardship of outside spending groups had a clear financial interest in giving upbeat assessments of Romney’s chances—were given prominent perches to hoodwink the viewers of Fox News and the readers of the Wall Street Journal. And as Media Matters‘ Simon Maloy documents, Jennifer Rubin, the Washington Post‘s pro-Romney blogger, expressed a far less sanguine view of campaign events after the election than she did when she covered them in real time.

The problem goes beyond the conservative media, however—even Republican-leaning pollsters like Rasmussen and Gravis Marketing proved poor predictors of the final outcome, while results from some Democratic-leaning firms like Public Policy Polling were actually closer to the final result than traditional powerhouses like Gallup.

All this has reopened the debate about “epistemic closure,” the term libertarian writer Julian Sanchez used* to describe the closed universe from which conservatives receive their information, in which those who deviate from the official party line are deemed apostates who are to be excommunicated. Erik Kain, writing at Mother Jones, says this is in part a business model: “There’s big money in controversy, and controversy is what the Glenn Becks of the world do best.”

Ideology can place blinders on everyone, of course—I don’t know how many liberal friends I’ve tried to talk out of their affinity for rent control—but the incentives for misleading one’s audience are not evenly distributed across the left-leaning and right-leaning media. The Romney surge after the first debate didn’t translate to a widespread liberal belief about systemic bias among polling firms, for example. Much of the conservative media is simply far more cozy with the Republican Party than its Democratic counterparts (as exemplified by the numerous Fox hosts and contributors who moonlight as Republican fundraisers), which makes necessary detachment difficult. Having an opinion isn’t an obstacle to good journalism or analysis, but no one wants to derail their own gravy train. Departing from the party line, particularly if one does so in a manner that seems favorable to Obama, would be to reveal one as an apostate, a tool of liberalism. There were independent-minded conservative analysts who diverged from this trend, but few were listening to them.

I think the business model theory works, but I would suggest that the problem lies not just with outlets like Fox but also with their audiences. That is, I think my original tweet, blaming the conservative media for misleading the readers who depend on them, doesn’t capture the fullness of the problem. Conservative media lies to its audience because much of its audience wants to be lied to. Those lies actually have far more drastic consequences for governance (think birthers and death panels) than for elections, where the results can’t be, for lack of a better word, “skewed.”

Perhaps that will change. Dean Chambers, the gay-baiting proprietor of Unskewedpolls.com, one of the alternate universes conservatives retreated to in order to reassure themselves of a Romney victory, told Business Insider that Scott Rasmussen, the owner of a Republican leaning polling firm “had a lot of explaining to do.” He’s not the only one.

*Correction: Sanchez didn’t coin the term; he was the first to use it in this context.