<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/jduf4/8202240718/sizes/c/in/photostream/">Duffernutter</a>/Flickr

Environmentalists waging an ongoing fight against the Keystone XL pipeline were dealt a major setback this week when Nebraska Governor Dave Heineman signed off on the pipe’s route through his state. Now all that stands between TransCanada, the company behind the pipeline, and broken ground is a signature from the State Department, the final decision about which is expected this spring.

Between now and then, the sprawling unofficial coalition of green individuals and groups that have bonded in the last two years over opposition to the pipeline is gearing up for a final push. It’s certain to be an uphill battle: Yesterday a letter signed by 53 senators put renewed pressure on Obama to say yes, and other than the rare rhetorical nod to climate action there are few clues that he’ll nix the project*. So the rhetoric of the next couple months could make or break the pipeline.

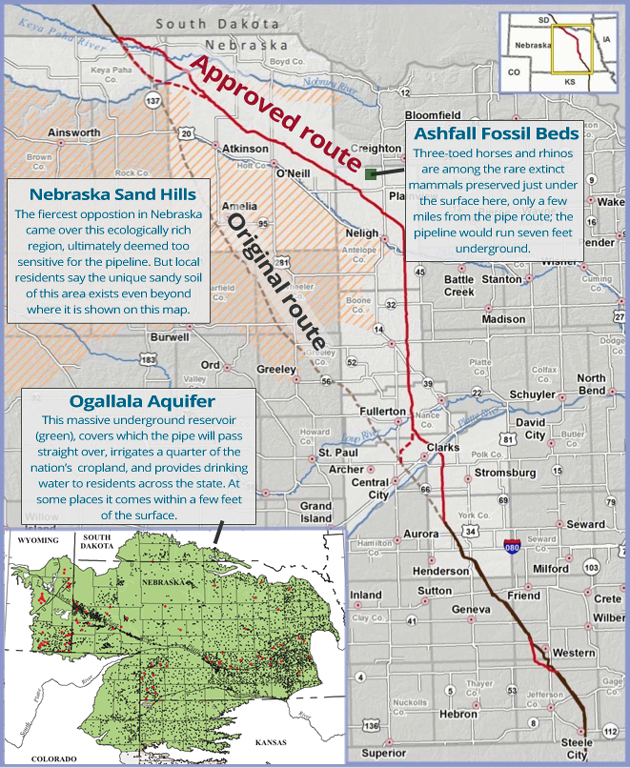

Opposition to the Keystone XL has tended to coalesce around two different arguments, the tools in the anti-Keystone toolbelt: The first is that the pipe could deal a deadly blow to the global climate by raising the floodgates for oil from Canada’s tar sands, believed by scientists to be one of Earth’s dirtiest fuel sources; the second is that the pipe could pose a slew of localized threats on its path from Alberta to the Gulf of Mexico, from potential leaks contaminating groundwater to careless work crews plowing through fragile dinosaur fossil beds. Governor Heineman’s decision seems to close the book on the state-level fight and steal some thunder from the localized argument, but leading Nebraska activist Jane Kleeb says local landowners aren’t ready to cede their home turf quite yet.

“Oh yeah, it’s far from over. We have landowners asking us to train them in civil disobedience,” Kleeb said. “These folks are not joking around. They homesteaded this land. They don’t trust this company. And they don’t want [the pipeline]. So they’re going to do everything they can to keep it from crossing their lines.”

Kleeb says although she’s made the global climate case to Nebraskans, in her experience the strongest battle strategy focuses on localized issues. She still has one ace in that hole: a lawsuit in Nebraska Supreme Court brought by a trio of landowners against Gov. Heineman, challenging the constitutionality of the state law that allows him to green-light the pipeline. So far the suit hasn’t slowed the governor down, but Kleeb is hopeful that if the case falls in her favor it could throw a wrench in the works, regardless of the State Dept.’s decision. And she continues to trumpet the risk the pipeline poses to water and ecological resources in her state, arguing that the state’s official map of the pipeline route misrepresents the size of the Sand Hills, a delicate Nebraska ecosystem that the pipe’s original route cut straight through but that the approved route purports to make a point of avoiding (see map).

But David Loope, a geologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, says perceived threats to the Sand Hills and Nebraska’s Ogallala Aquifer, which the pipe is still plotted to cut across, are overblown.

“I’m conflicted,” he says. “I think the pipeline is a terrible idea for global reasons. But the hew and cry coming from Nebraska is pure NIMBYism.”

Loope says the global climate change argument against the pipeline is far more honest, and he hopes to see that prevail as the leading opposition rallying cry in Washington, DC. There’s a good chance it will: Bill McKibben, the environmentalist who’s become the Keystone XL’s most public opponent, said in an email that while he’d love to help save Nebraska, putting climate front and center is the best way to save the rest of the world, too: “The fight has always been about whether the president actually means what he says about about fighting climate change. We’ll find out.”

Correction: The original version of this article stated that there were few clues that Obama will approve the project. In fact, the opposite is true. Climate Desk regrets the error.