<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/soukup/5160027836/sizes/l/in/photostream/" target="_blank">soukup's photostream</a>/Flickr

In the mainstream political press, the standard practices of neutrality and balance carry with them an implicit assumption: that Democrats and Republicans are separate but equal in their ideological biases, with each group just as inclined to support its own team and attack the other side. The trouble is, data from psychologists and political scientists suggest that this might be a naive approach. At worst, it may fundamentally misunderstand the nature of American politics.

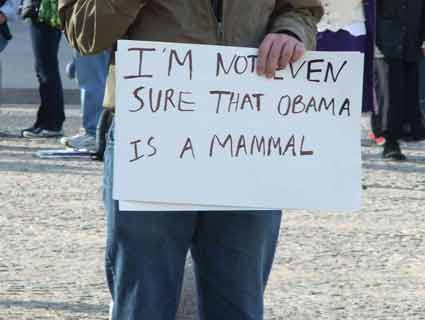

The latest evidence on this head comes from pollster and political scientist Dan Cassino of Fairleigh Dickinson University. In a national survey, Cassino examined belief in political conspiracy theories on both the left and also the right. He did so by asking Americans about two “liberal” conspiracy beliefs—the 9/11 “Truther” conspiracy, and the idea that George W. Bush stole the 2004 election—and two conservative ones: the “Birther” theory that Barack Obama was born in Kenya, and the claim that he stole the 2012 vote.

The results were hardly symmetrical. First, 75 percent of Republicans, but only 56 percent of Democrats, believed in at least one political conspiracy theory. But even more intriguing was the relationship between one’s level of political knowledge and one’s conspiratorial political beliefs. Among Democrats and independents, having a higher level of political knowledge was correlated with decreased belief in conspiracies. But precisely the opposite was the case for Republicans, where knowledge actually made the problem worse. For each political knowledge question that they answered correctly, Republicans’ belief in at least one conspiracy theory tended to increase by 2 percentage points.

What’s up with this? Cassino views these data as just one more indicator of an “asymmetry” in how Democrats and Republicans, or liberals and conservatives, respond to politics—with Republicans tending to be more partisan and tribal (and in this particular case, more willing to believe conspiracies about their political opponents), and Democrats less so. And while Cassino admits that his latest study wouldn’t, in and of itself, constitute definitive proof of ideological asymmetry, he thinks it fits into a bigger body of evidence.

Consider: Over the last 50 years, partisan “crossover”— voting for a presidential candidate of the other party—has been anything but equal or symmetrical. Crunching the data, Cassino found that since 1952, on average Democrats were almost twice as likely as Republicans to vote for the other side’s presidential candidate.

Then there’s presidential approval ratings. Going back over the last half century, Cassino has found that Republicans rate presidents of their own party considerably higher than Democrats do, showing stronger party loyalty. More specifically: In a 2007 paper with his colleague Matthew Lebo, Cassino found that Republicans had shown 90 percent approval for Republican presidents much more frequently over the past half century than Democrats had for Democratic presidents. Eisenhower had 28 months of this intense support, and George W. Bush had 38 months of it, followed by George H.W. Bush (14), Reagan (13), and Nixon (2). By contrast, Democrats only showed the same level of support during 12 months of the Clinton years and 5 months of the John F. Kennedy years. At the same time, note Cassino and Lebo, Republicans were also tougher on Democratic presidents than Democrats were on Republican ones.

Finally, consider how Republicans and Democrats respond to performance of presidents from the opposite party on the economy. In the same paper, Cassino and Lebo found that while Democrats respond to Republican presidents who decrease unemployment by increasing their support, Republican support decreased when Democratic presidents created jobs (or saw jobs created on their watch). “There’s very little a Democratic president can do to get Republican approval,” Cassino says.

What’s behind all of this? There are probably multiple factors—ranging from psychological to sociological. For instance—and as I wrote about in my book The Republican Brain—conservatives are known to have a higher need for cognitive closure—the desire to have a fixed belief, an unwavering sense of certainty, about politics and all aspects of life. If belonging to their party or group confers such a sense of closure, then it makes sense that conservatives would be more likely to interpret the world in partisan, black-and-white terms, believing negative conspiracy theories about the other side and refusing to support its leaders. Indeed, the noted moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt has found that Republicans are simply more tribal about politics, more loyal and favoring of their in-group (see Figure 1).

Plus, there’s little doubt that the rise of partisan media helps fuel partisan animosity and divergent realities. But whatever the ultimate cause, the idea that everybody is equally biased, but in different directions, continues to have a key weakness—namely, the data. And if these results—and they’re not the only ones of this ilk, see for instance here and here—are really true, then it may not be a good thing for democracy to perpetuate this idea that everyone has equal biases. As Obama begins a second term after four years of implacable resistance, that’s something to ponder.