Whitebark pine trees dying from pine beetle infestation in Bridger-Teton National ForestDavid Gonzales/<a href="http://www.treefight.org/">TreeFight.org</a>

Mountain pine beetles have spent the last decade decimating more than 4 million acres of forest in the Rocky Mountain West. Beetles are a natural part of the forest ecology, picking off old or unhealthy trees and keeping the healthy ones resilient. But a warming planet—2012 was the hottest year on record—means not enough beetles die off in cold snaps. Instead, they produce more quickly, boring under bark, laying eggs, and weakening trees until they die.

And now, the continuously warm weather has emboldened these creatures to flourish in forests of whitebark pines—stately old trees that survive at high elevations—as well. In a new report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team of University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers describe the beetles’ deadly effect on whitebarks in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

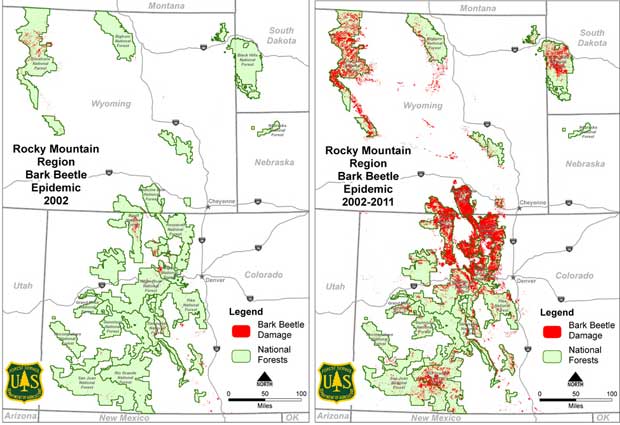

2002 2011

Photographer and activist David Gonzales has spent much of the last four years poking around that ecosystem, venturing into the high-altitude whitebark pine stands of Wyoming’s Bridger-Teton National Forest to attempt to defend these ancient trees from the explosive beetle epidemic, a practice he’s deemed “treefighting.” Along with volunteers and students, Gonzales spent three years tacking pouches of pheromones onto individual trees to try and trick beetles into thinking they were already inhabited, though he has mixed feelings about guiding beetles from one tree on to another. This past year, Gonzales’ group planted 3,000 young whitebark saplings, which if they survive the planting process, can live for a millenium.

Ecologists consider hearty whitebark pines to be a keystone species of the northern Rocky Mountains: The trees’ nutrient-rich seed cones provide sustenance for grizzly and black bears, several bird species, and squirrels; their roots prevent erosion in thinly soiled peaks; their branches serve as wind barriers and shade snowpack at high elevations, meaning snow sticks around longer and less water evaporates before summer months. “They pick the places that other plants can’t survive—bad soils, really dry,” says GIS specialist Wally MacFarlane in Gonzales’ 2011 documentary Seeing Red, about beetlekill in the Yellowstone area. “You kind of appreciate them for that—their ruggedness.” Gonzales certainly does. “They live in the absolute worst conditions, yet they produce the best plant-based fat and protein in the ecosystem, and are paragons of energy efficiency,” he says. “They are showing us that we can do a much better job of dealing with our own energy.”

But unlike neighboring lodgepole pines, which co-evolved with the pine beetle and developed defenses against the bug, whitebark pines are very vulnerable to beetle attacks, since they haven’t evolved to create enough of the compounds (like resin) that repel or kill bugs or disrupt their communication systems, according to the Wisconsin study.

The research did reveal one hopeful sign: When the beetles entered areas mixed with lodgepoles and whitebark pines, the critters were more likely to choose lodgepoles over whitebarks.

A mountain lover and avid skier, Gonzales has watched mountain pine beetles spread through 95 percent of the whitebark forests in greater Yellowstone, leaving many mountainsides a rusty grey color from dead trees. The hard part, he says, is that given that the trees already grow at the highest altitudes, “there’s nowhere else for them to go; they can’t find higher ground.”

Gonzales says around 75 percent of the whitebarks he planted with his crew in June seemed to have survived when they checked back on the saplings in September, and he plans to try and plant even more in the summer of 2013. And treefighting seems to be catching on: Student groups from as far away as Brooklyn and Hanover, New Hampshire, came to plant trees and document changes in whitebark stands this past year. Gonzales celebrates the growing attention and involvement, but remains pessimistic about the forests’ susceptibility to beetles and climate change: “I think we’re going to see more tree species affected. Unfortunately, treefighting is going to become a growth industry in the coming years.”

Trees dying from beetle infestation often turn a reddish color, like these in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. David Gonzales/TreeFight.org