A post-Newtown candlelight vigil.Michael Mcandrews/MCT/ZUMA Press

Garen Wintemute, an emergency physician and director of the Violence Prevention Research Program at the University of California-Davis, is a pioneer in the study of gun violence as a public health issue. In his latest report, he argues that background checks should be required not just for licensed dealers, but for the roughly 40 percent of firearms sales that take place via private parties. That would mean requiring background checks for purchases at gun shows as well as for all sales between individuals.

Closing the “gun show loophole” alone isn’t enough, Wintemute says, because the shows account for only a small percentage of private sales. Universal background checks are among the measures being considered by Congress in the wake of the Newtown massacre. Other proposals would ban assault weapons, impose tougher penalties for people who buy guns illegally for others, and give schools money to beef up safety and security. (A Senate panel has approved proposals involving several of these items.) I spoke with Wintermute about internet gun sales, whether something tough might actually make it through Congress, and how it is that a guy can look for all the world like a major gun dealer yet claim he isn’t one.

Lilly Fowler: How did you get interested in gun violence?

Garen Wintemute: I was an ER doctor in the Sacramento area and was interested in preventing the sorts of injuries that I was seeing. I was aware of the fact that the vast majority of people who die from gunshot wounds die where they are shot. It doesn’t matter how good the medical care is. So if I as a clinician want to make the biggest inroads, I need to work on preventing them from being shot in the first place.

The disparity between the size of the problem and the number of people researching it is unique. Here is a health problem that causes more than 30,000 deaths a year. There are probably somewhere between double and triple that number of permanently disabling injuries. And yet in the entire country, counting all academic disciplines together, there are fewer than a dozen experienced, active researchers in the field trying to figure out what to do about it. If we were talking about any other health problem, that simply would not be a tolerable situation.

LF: Will you briefly describe your recent report and its recommendations?

GW: We work very hard to prevent prohibited people, most of whom are thought to be at high risk for doing crime, from acquiring firearms. Everybody thinks that it is a good idea. But we do that only when the firearm is being acquired from a licensed retailer. We know based on several studies that something like 40 percent of all firearm acquisitions in the United States, and at an absolute minimum 80 percent of acquisitions made with criminal intent, are made from private parties.

If I buy a gun from a licensed retailer I have to show my identification. I have to fill out a lengthy form and certify that I’m not a prohibited person and I’m buying a gun for myself. The retailer has to initiate a background check. And obviously I can’t acquire that gun if I fail. But [in most states] I can buy that same gun from a private party and none of those safeguards applies. If I am prohibited person, the private parties who sell me a gun commit a crime only if, at the time they sell it to me, they have reasonable cause to believe that I’m a prohibited person.

I have done field research at close to 80 gun shows all over the country. A private party vendor might have a table with 50 guns on it and a little sign that simply says, “private sale.” And everybody knows exactly what that means. It means there will be no record keeping, no background check. But it also means, “I won’t ask questions and don’t you volunteer any incriminating information.” That’s how the system works.

Gun shows are where you can see it happening, but if you ask people where they buy their guns, it’s clear that gun shows themselves account for a relatively small percentage [between 4 percent and 8 percent] of private party gun sales. I bring all this up, because people talk about closing the gun show loophole as an approach to this whole problem—and closing the gun show loophole by itself would just be a waste of time.

LF: What’s the difference between the guy with the “private sale” sign and a retail outlet?

GW: If you are engaged in the business of buying and selling firearms, then you have to have a license. But in the mid-1980s Congress passed, and President Reagan signed, a piece of legislation known as the Firearm Owners Protection Act that specifically made as ambiguous as possible the definition of what it meant to be engaged in the business. The upshot was that you could go to a gun show and see people who have elaborate displays and hundreds of guns, and they could claim just to be collectors or hobbyists, and get away with it.

LF: Some states have already adopted the background checks you’re recommending. What’s happened in those states?

GW: There are six states that require a background check and a permanent record for essentially all transfers of firearms. [California, Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island—on March 15, New York becomes the seventh.]

In California, we’ve had a comprehensive policy in place for more than 20 years. It does not paralyze commerce in firearms. We move more than 600,000 guns a year through that system. The state’s rates of firearm violence are below average. I can’t say what that’s attributable to, but we do know this policy clearly interferes with the movement of firearms from the legal market to the illegal market. There’s a yardstick that’s called “time to crime”—the time between a gun’s retail sale and its recovery by law enforcement after it’s been used in a crime. In most states, guns that are less than three years old account for a very large percentage of guns used in crime. Here in California that is much less true. It’s not perfect, it doesn’t work all the time, but there’s a clear net effect in disrupting criminal gun commerce.

The new development here is the internet. I can sit at my own breakfast table and go shopping for guns, and I don’t have to go to a gun show. We can arrange to meet at someone’s house, or a McDonald’s parking lot—it doesn’t matter. That’s completely off the radar.

LF: What do you say to people who argue that these kinds of regulations don’t work, that criminals will always find some way to get guns?

GW: All of the research evidence shows that increasing regulation of firearms—whether the firearms themselves, the people who are allowed to have them, or the conditions under which they are bought and sold—makes a difference. I think it can be hard to prove that any one law makes a difference because laws are enacted in groups, or one right after the other, but there’s just no question in my mind, looking at the hundreds of studies that have been done, that regulating commerce and use of firearms prevents violence.

LF: Who are the “prohibited people”?

GW: We prohibit felons and people who are under felony indictment. A paradox: The only misdemeanors we prohibit people for are domestic violence misdemeanors, at least under federal law. Other than in California and a few other states, I could have a record of misdemeanor violence as long as my arm and still purchase as many firearms as the law otherwise allows: That’s nuts.

LF: Federal background checks have been in place only since 1994. I imagine they have had some kind of impact?

GW: Yes. In 2009, state and federal agencies ran 10.7 million checks, although not all of them were for firearm purchases. Some of them were for permits to carry concealed weapons. And generally about 1.5 percent of those led to denials. That sounds like a small percentage, but 1.5 percent of almost 11 million is a lot of people. And that’s a good thing. Most of the denials are for people who have been convicted of crimes. So one can make the simple, intuitive case that the system is preventing high-risk people from acquiring guns.

LF: Can you talk about the gun industry’s influence on the regulatory landscape?

GW: The role of the NRA as a political force is relatively recent. Up until the late 1960s, the NRA was not particularly interested in politics. But over a series of developments they became very much involved and worked hard on campaigns and worked hard on legislation. The NRA simply did not have, at least not across-the-board, the power to call the outcome of an election the way people think. They got a boost from their opponents who ceded to the NRA more electoral power than it actually had.

The Democrats were looking for a scapegoat to explain some of their own poor performance, so the gun issue got blamed for Al Gore’s defeat when there’s good polling data to show that simply wasn’t the case. And in other instances I think the NRA’s reputation was inflated not just by them but by their opponents, who were looking to get themselves off the hook.

What’s happened more recently is this. Beginning in 2012, Michael Bloomberg, to identify one person, recognized the need for a long-term financial counterweight to the NRA. The NRA has not had a financial opponent in the game. Bloomberg committed money to several races in the 2012 cycle.

And then Sandy Hook came along, I think we are now seeing not just Bloomberg’s organization, but a new organization headed by Gabby Giffords and Mark Kelly, Americans for Responsible Solutions. Elected officials concerned about their own political futures don’t have just one voice to listen to now, but they probably have several, all of them backed by substantial pocketbooks. I think that’s going to change the game.

LF: There is a sense of urgency about gun control. Do you attribute it mainly to Sandy Hook?

GW: I’ve been doing this for 30 years. I’ve never seen this much interest in doing something about firearms. I think people probably, in their minds, simply cannot walk away from that event without doing something about it. But it’s not just Sandy Hook. The week before Sandy Hook, kids waiting in line to see Santa Claus at a shopping center in Portland had to run for cover. It hadn’t been long before that that people going to temple in Wisconsin were shot. Not long before that there was the Aurora shooting. So Sandy Hook reminded people of the tragedies about which nothing had been done.

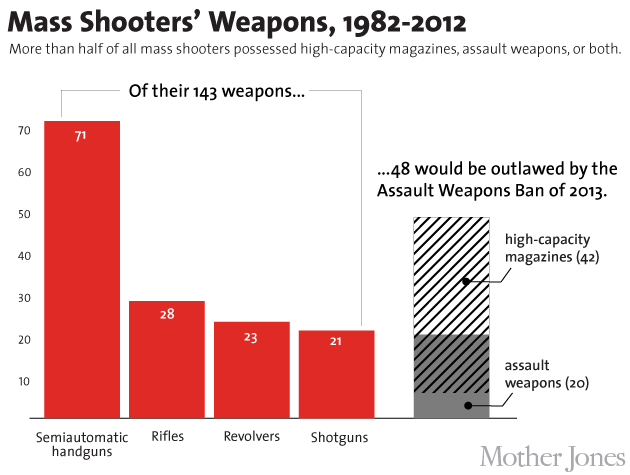

Take Sandy Hook and the Oak Creek temple shootings and Aurora and Virginia Tech and Columbine—all of them together killed 95 people. That is a lot of people, but we lose on average 88 people every day to gun violence. We have another more than 200 seriously injured every day. And people got that—that if we focus on mass shootings, we’re setting ourselves up to lose on two grounds. Number one, they are all different and we can’t tailor-make a solution. And number two, we recognize that, as horrific and riveting as these events are, the bigger problem is the endemic violence that we don’t notice unless it somehow touches close to home.

LF: Do you think Congress and state legislators are going to do anything significant this time around?

GW: I think there’s a better than 50 percent chance that we will get something that looks like comprehensive background checks, and that will be an important change, probably more important even than people realize. I keep thinking about how 80 percent of guns that are acquired with criminal intent are acquired from private parties. I think we should do everything we can to make that harder to do. I have eaten, breathed, slept this issue for 30 years, and it was clear to me by the Friday afternoon [of the Sandy Hook shootings] that this was the moment I had spent those 30 years getting ready for.

FairWarning is a nonprofit investigative news organization based in Los Angeles that focuses on public health and safety issues.