Fight disinformation:

Sign up for the free

Mother Jones Daily newsletter and follow the news that matters.

When photographer Donald Weber traveled to Turkey and Syria in 2003 to document Kurds, the Iraq War was just beginning. As the United States invaded the region and the conflict escalated, Weber saw firsthand what life was like for a population that has been persecuted throughout its history.

The Kurds—a primarily Sunni Muslim group and the largest stateless people in the world—have been attacked and abused at various times by the five bordering nations they inhabit: Armenia, Syria, Turkey, Iran, and Iraq. The most infamous example occurred in Iraq in the 1980s, when Saddam Hussein unleashed a campaign of lethal biological warfare, gassing thousands and destroying nearly 4,000 Kurdish villages. Living with Kurds at the start of the Iraq War, Weber found them “jittery,” and ever fearful that “government forces would crack down on their political aspirations, as Saddam Hussein had done with his mass gassings.”

Upon returning to Kurdistan in 2011, what Weber saw was radically different. In northern Iraq, home to about 6 million Kurds, he found a bustling, functional society. In 2005, Iraq’s new constitution granted Iraqi Kurdistan substantial autonomy, and since then the state has grown rapidly: It has established a separate parliament, elected a president, and drawn hundreds of investments from dozens of countries—from the United States and Germany to Turkey and the rest of the Arab world. “An autonomous republic,” Weber says, “was born in the smoking crater of war.”

In this photo essay, Weber provides a glimpse into this new community, one still grappling with the growing pains of nation building, the balance of tradition and modernity, and the knowledge that violence—part scourge, part enabler of their prosperity—is always uncomfortably possible.

At an amusement park in Sulaimani, Iraq, located in the Kurdish semiautonomous republic.

A photo of a boy killed during a gas attack in Halabja, Iraq, in 1988 by Saddam Hussein’s forces hangs in a museum in Sulaimani, in memoriam to the more than 5,000 Kurds killed in the attacks.

A female peshmerga, or soldier, during training camp where they are learning to be combat soldiers. The first female peshmerga unit was formed in 1996, with just a few women joining. Today, there are hundreds of female peshmerga working in various capacities, from combat soldiers to bodyguards and security patrols for Kurdistan government officials and buildings.

When the Kurds created their own semiautonomous state in the north following the United States’ 2003 Iraq invasion, they created jobs, a bustling economy, the chance to educate their young, and stability, something they have not had in decades.

Another female peshmerga during training camp. Literally translated as “one who faces death,” the peshmerga began as a militia of sorts. Though still defined as such by some, most Kurds find this terminology inappropriate and consider them the official army of Iraqi Kurdistan, given the group’s formal structure.

A woman works at a call center in Sulaimani. While still very much a patriarchal society, Kurdistan is very open and liberal by Middle Eastern standards, allowing women to work in positions of influence, travel alone after dusk, and generally to be independent.

An unknown woman’s headshot sheet, picked up at a Kurdistan photo studio.

A diorama of a dead boy and girl based on photographs at a museum in Halabja, Iraq, the locale where Saddam Hussein’s regime gassed more than 5,000 Kurds in an attempt to quell their brewing rebellion.

A father and son enjoying a Friday picnic in Dukan, just outside of Sulaimani, which is the cultural and business capital of Kurdistan. Many of the rebel leaders of the last 40 years were from Sulaimani, and today it wields important influence over the state of Kurdish affairs.

Female peshmerga during training camp

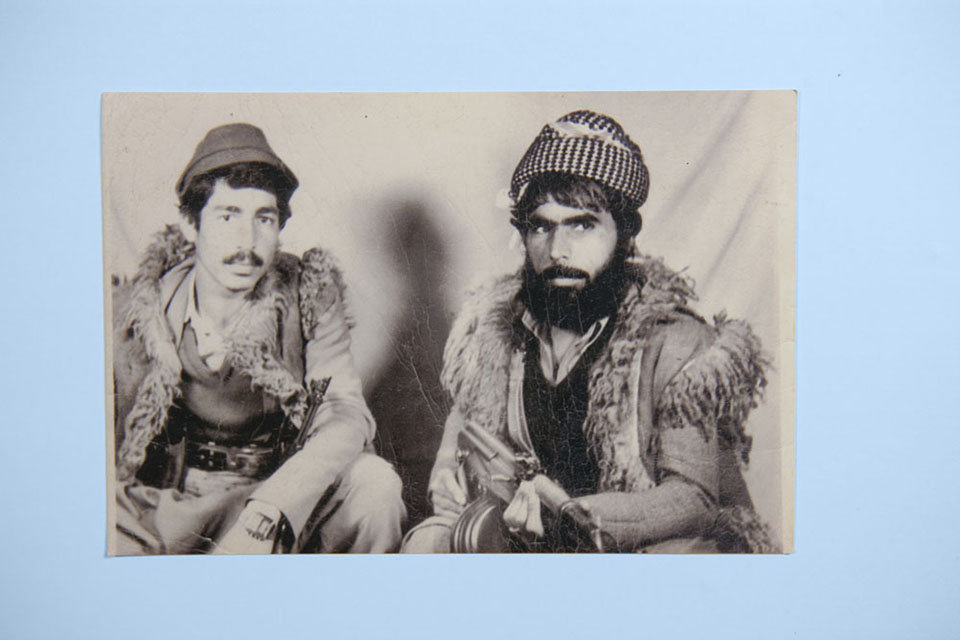

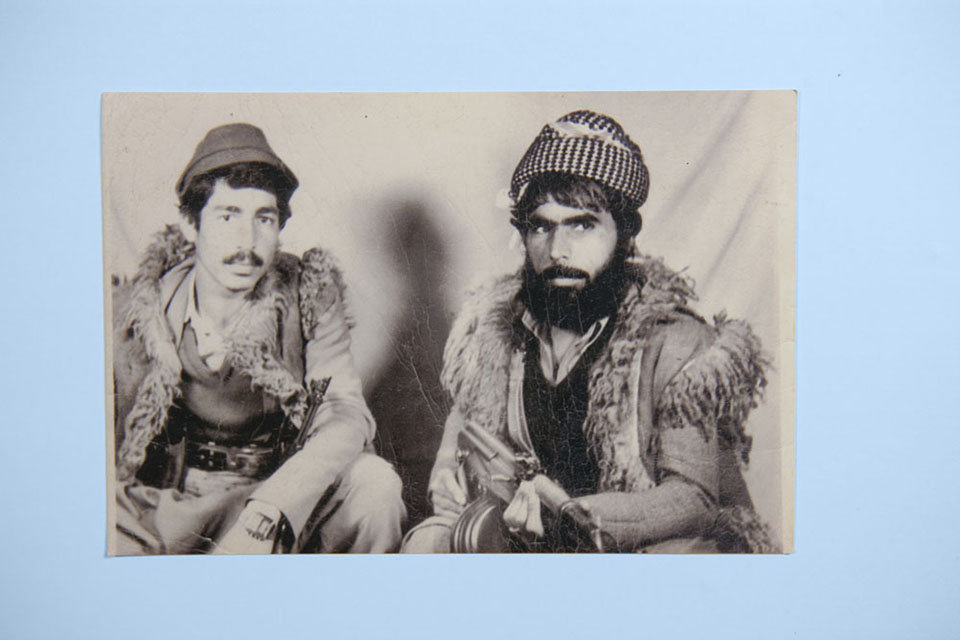

An old photograph of two peshmerga from Kurdish Iraq. The rebel movement that began in earnest in the late 1960’s and 1970’s, saw new momentum with the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003.

Kurds celebrate their traditional new year, Newroz, long informally prohibited under Saddam Hussein and now the biggest holiday of the year. In Kurdish legend, the day celebrates the deliverance of the Kurds from the tyrant King Zuhak, a monster with two serpents growing from his shoulder who feeds on small children’s brains. For many, this holiday has become a symbol of Kurdish national struggle, and the legend a metaphor for the Kurd’s deliverance from Saddam Hussein, a latter-day King Zuhak.

The Ahmed family from Sulaimani enjoys a picnic on the day after Newroz, the Kurdish new year. Many of the family’s members emigrated to Canada, the United States, and Germany for safety and opportunity 20 years ago; today, many emigrants are returning to their homeland to open businesses, get in touch with long lost family, or just finally come home.

A boy climbs on top of a tank at a museum housed in a former prison and military barracks in Sulaimani. Upon entering the museum, an inscription reads: “We neither manufactured these weapons, nor feel proud exhibiting them. In fact, these were used by those who threatened our very existence. We also admit that these very weapons helped us achieve our freedom.”

Tourists atop a miniature village in Sulaimani. The Kurds are a traditional mountain people, with more than 30 million of them spread throughout Iran, Iraq, Turkey, Syria, and Central Asia.

A woman at a shooting gallery in Sulaimani.

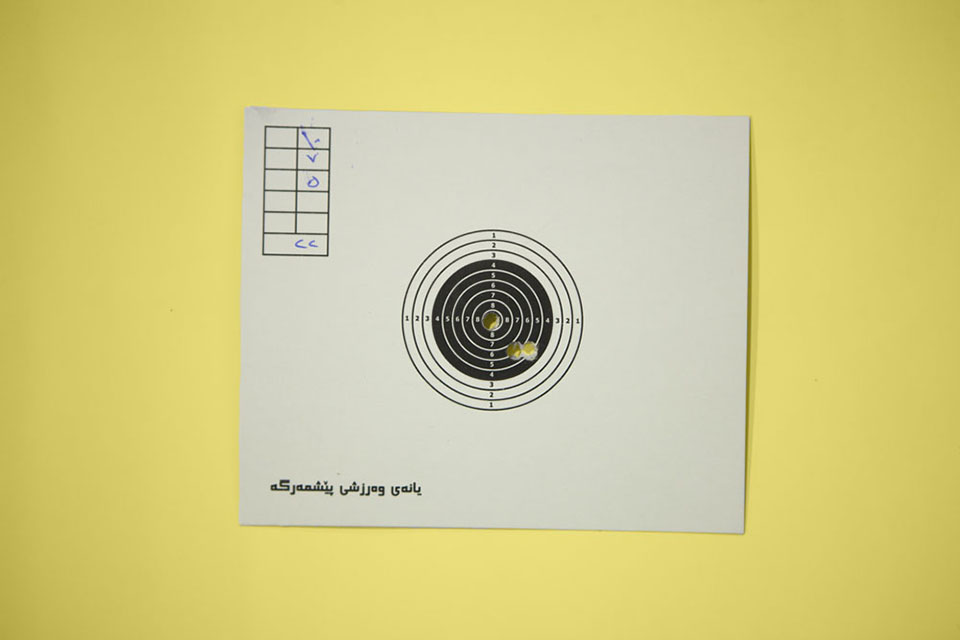

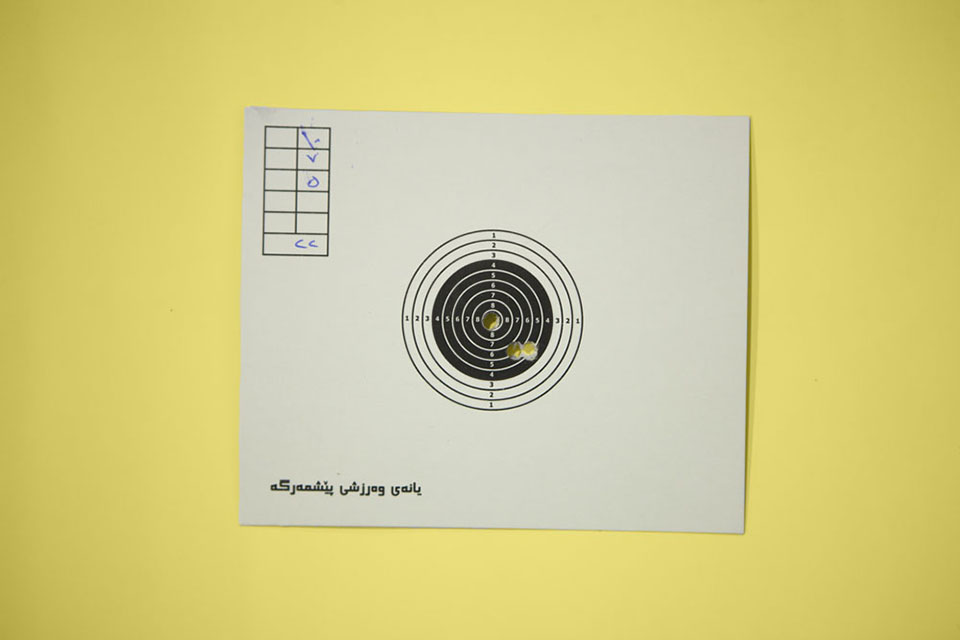

A target as shot at by a female member of the local target shooting club. While still very much a patriarchal society, Kurdistan is very open and liberal by middle eastern families, allowing the women to work in positions of influence, be on their own after dusk and generally be independent women.

In the central Erbil market as the day ends, a man stands all dressed up with nowhere to go. Although great gains have been made in the new, semi-independent Kurdistan since 2003, there is still a long way to go in developing the infrastructure, both economic and social, to secure the autonomy and success of the Kurdish state.

This project was developed with support from the Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund, in partnership with Mother Jones. The Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund supports experienced photographers with a commitment to documenting social issues, working long-term, and engaging with an issue over time.