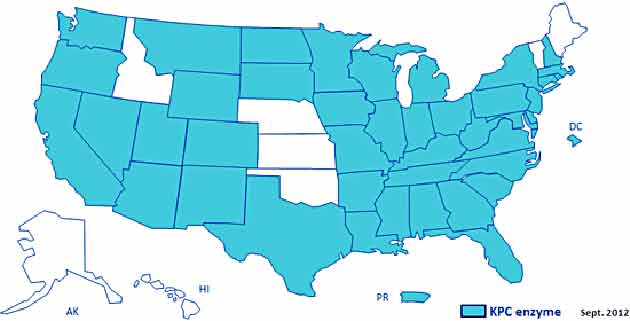

States with confirmed CRE cases.CDC

The news on antibiotics just keeps getting worse. In the past decade, methicillin-resistant staph aureus—better-known as MRSA—and clostridium difficile (“C. diff” for short) emerged as poster-bugs for antibiotic-resistance. This week, the Centers for Disease Control trumpeted alarming findings about another group of lethal, antibiotic-resistant microbes that has spread in recent years to hospitals across the country.

These “nightmare bacteria”—as CDC director Dr. Tom Frieden dubbed them this week—are called “carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae,” or CRE. In healthy people, dozens of enterobacteria species live in the digestive system and pose no threat. In hospital patients with weak immune systems, however, they can cause devastating infections, especially when they acquire resistance to the antibiotics known as carbapenems. These drugs have long served as the treatment of last resort for enterobacterial infections resistant to other antibiotics.

Between 2001 and 2011, according to the CDC’s new report, the proportion of resistant cases of enterobacterial infection more than tripled, from 1.2 to 4.2 percent. And a 2012 survey of acute-care hospitals found that almost one in twenty reported at least one CRE case during a six-month period. The agency did not report the number of deaths from these cases; however, earlier studies found mortality rates of up to 50 percent.

What alarms health care experts is how easily this resistance trait can spread. In bacteria, resistance often arises from genetic mutations. In contrast, CRE carry genes for enzymes that deactivate the carbapenems. These gene packets can be passed along whole to bacteria of the same or even different species–a highly efficient method of disseminating antibiotic resistance. In hospitals, the bacteria are transmitted through hand contact and infected equipment.

An outbreak of klebsiella pneumoniae, an enterobacteria species, swept through a National Institutes of Health research hospital in Bethesda in 2011, infecting 18 patients and killing six. The six-month outbreak began in June that year with the transfer to the NIH hospital of a 43-year-old New York patient with a history of persistent infections.

The incident demonstrated that standard procedures at even the most prestigious medical centers were not sufficient to stem an outbreak of these pathogens. Although CRE infections still remain relatively uncommon in the United States, the CDC warned in its report that the bacteria “have the potential to move from their current niche among health-care–exposed patients into the community” and urged health-care facilities to intensify infection control efforts.