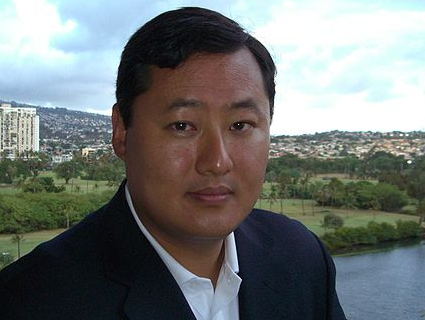

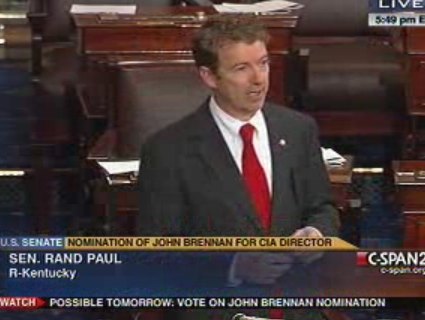

Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.).<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/circulating/4364735824/">circulating</a>/Flickr

Some supporters of Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) think he got a bum rap from critics of his speech at historically black Howard University this week. Andrew Sullivan wrote that “the sheer lack of any grace among some liberal commenters on what was an obvious outreach to African-Americans depresses me.” Others, like National Journal‘s Josh Kraushaar, who gave Paul a hearty pat on the back for “showing up to make a case,” were impressed that Paul went to Howard in the first place.

We can count Paul among the people impressed that Paul showed up. “Some people have asked if I’m nervous about speaking at Howard,” Paul joked. “They say ‘You know, some of the students and faculty may be Democrats.'” That landed like a brick on a concrete slab. After that, as though Paul had spent no time learning about Howard itself, Paul proceeded to lecture his audience on the history of black voters and the Republican Party, using the abridged version preferred by Fox News pundits: Lincoln freed the slaves, Democrats were the party of the Jim Crow, so black people should vote Republican. Paul mangled the name of one of the only elected black senators and a Howard alum, Massachusetts Republican Edward Brooke, calling him “Edwin Brooks,” and then asked the audience if they knew that the founders of the NAACP were Republicans. The people in the audience replied, laughing and incredulous, that they did. Later he tried to whitewash his position on the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and an audience member pointed out that Paul’s opposition to a key provision of the act was “on tape.”

From his first lame joke, Paul condescended to his audience by repeatedly underestimating their knowledge of a subject they almost certainly understand better than he does. Institutions like Howard exist in part because much of America once refused to educate blacks and whites together. Paul might as well go to NASA to lecture the scientists on astrophysics.

Also strange is the presumption that somehow Paul was doing something risky or brave by speaking at a historically black college. Howard University is not a Greyhound bus station at midnight. It is way past time for pundits to retire the notion that white politicians deserve extra credit for being willing to talk to a room full of black people. This is, as one Republican once put it, the soft bigotry of low expectations. The history of Republican politics and the conservative movement means that a black audience has every right to be skeptical of the GOP, and that the burden is rightfully on that party to reconcile with black voters. Politicians are supposed to reach out to voters, not the other way around. No more gold stars for attendance.

The official Republican history of race in America should no longer ignore the fact that Republicans abandoned black people after Reconstruction in the name of “reconciliation” between North and South or elide the party’s post-1964 embrace of the politics of white racial resentment. That the party that was once the party of Jim Crow now gets upwards of 90 percent of the black vote is not an indictment of the Democratic Party. It is an indictment of the Republican Party.

Some of Paul’s defenders, such as The Atlantic‘s Conor Friedersdorf, have complained that Paul was unfairly mocked as being “hilariously backward about race,” even though Paul’s positions on war and drug enforcement are much more progressive than other politicians, including many Democrats. Aside from the fact that the Howard audience was quite receptive to Paul on those issues, it’s beside the point. In college, I used to hear all the time from liberals that simply being liberals somehow meant that they couldn’t do or say anything racist. Paul wasn’t being unfairly mocked for his positions on America’s various wars against abstract concepts. He was justifiably mocked for dishonestly condescending to his audience. Having the “correct” politics no more absolves him of that than they would the annoying campus liberals I encountered as a college student.

Paul’s unorthodox (for a Republican) positions on drug enforcement and national security, and even his recent shift on immigration, make him a better messenger to minority voters than most for Republicans. They reflect an admirable empathy for the marginalized and less powerful that the Republican party in general rarely expresses. Despite its misses, during Paul’s Howard speech you could hear the beginnings of a small-government message that might appeal to minorities. But if that message is delivered with a comical underestimation of those who are meant to receive it, then don’t be surprised if they toss the envelope in the trash without opening it.