I happen to know this guy who knows a lot about mental-health policy. And, well, okay, he happens to be my father. So my ears perked up recently when my dad mentioned that the DSM-5, the latest in a series of diagnostic manuals soon to be published by the American Psychiatric Association, is something of a disaster.

Indeed, at the end of April, the National Institute of Mental Health (the branch of the NIH that funds mental-health research) took the drastic step of renouncing the latest DSM (short for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) in advance of its publication—renouncing the whole DSM system, really—and replacing it with something called Research Domain Criteria.

“Basically, they said they would no longer use it as a main test in grant requests,” explains psychiatrist Allen Frances, who chaired the task force that produced the prior version, DSM-IV (past editions used roman numerals), during the 1990s. “They made it sound like DSM-5 and all the DSMs were invalid, and that we should wait for the new discoveries that were going to come from scientific endeavors.”

Frances considers the NIMH’s move misguided, but he’s no fan of the DSM either. That much is clear from his new book, Saving Normal: An Insider’s Revolt Against Out-of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life. (The New York Times reviews it here.) Given the current upheaval in psychiatry, and the impending release of the new diagnostic manual, Frances seemed like the man to bring us up to speed on how the DSM got so bloated, and why so many Americans are popping uppers and antidepressants that we don’t need.

Mother Jones: What you mean by “saving normal”?

Allen Frances: There’s been a rapid diagnostic inflation over the course of the last 35 years, turning problems of everyday life into mental disorders resulting in excessive treatment with medication. Pretty soon everyone’s going to have a mental disorder or two or three, and it’s time we reconsider how we want to define this and whether the definitions should be in the hands of the drug companies, which is very much what’s happened in recent years.

MJ: To what degree has this trend accelerated lately?

AF: We were very, very conservative in doing DSM-IV, which came out in 1994. Despite our efforts to tame diagnostic inflation, the rates of attention deficit disorder (ADD and ADHD) have tripled, the rate of autism increased by almost 40 times. The rate of childhood bipolar disorder increased by 40 times. And the rate of adult bipolar disorder doubled. A lot of this was driven by the drug companies. They had new products on patent—very expensive; it gave them the means and the methods to spread the message to doctors and patients that mental disorders were easily diagnosed, often missed, caused by chemical imbalance, and treated with an expensive pill.

MJ: How do they assert themselves in the DSM process?

AF: They don’t assert themselves at all in the DSM process. They have absolutely no contact with anyone. But they wait on the sidelines, and if something can possibly be misused in DSM, it will be misused. The drug companies have marketed heavily to primary-care doctors, who now prescribe 80 percent of psychiatric medication. That is amazing. Most psychiatric diagnosis is being done in seven-minute sessions with doctors who are not very interested or well trained in psychiatry.

MJ: By now, overtreatment of things like ADHD has become a cultural meme. What’s an example we might not have heard of?

AF: Well, probably the most overtreated is depression. The DSM system has lumped together really severe depressions that are totally incapacitating and definitely require medication with mild depressions that may just be an expectable reaction to everyday life. The mild depressions have a tremendously high placebo response rate—over 50 percent. The severe depressions don’t respond to a placebo.

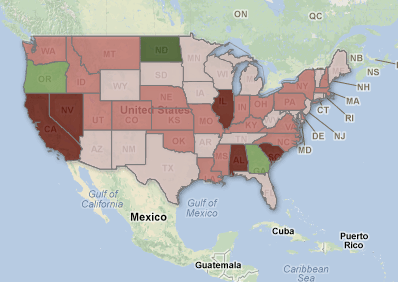

We have a terrific misallocation of resources in this country, with the severe depressions being very much undertreated; only one-third of people with severe depression get treated for it. At the same time, we’re terribly overtreating the mild depressions with medication. Eleven percent of the population takes an antidepressant. In the female 40-to-50 group, it’s 23 percent.

Studies show that probably about two-thirds of the people taking an antidepressant don’t need it. If you get an antidepressant after a seven-minute visit with a doctor on the worst day of your life, you’re going to get better—the placebo response and just time. But if you’ve taken the pill, you’ll assume the pill made you better, and so you’ll tend to stay on the pill. So you have lots of people taking medicine they don’t need for problems that will take care of themselves, and people who really do need medicine don’t have access to treatment.

MJ: Why not?

AF: The budgets have been cut dramatically for mental health. We now have a million psychiatric patients in prison for nuisance crimes because they weren’t given adequate care as outpatients and a decent place to live. As Obama put it, it’s easier now for someone who’s mentally ill to get a gun than to get an outpatient appointment.

MJ: Who is most to blame for the larding up of the DSM-5 with dubious diagnostic criteria?

AF: A lot of the blame falls on experts being given too much freedom to expand their pet diagnoses and areas of interest. I’ve been working in this area for 45 years and I’ve never met an expert who said, “Let’s shrink my area.” They always want to expand it. They always worry about missed patients. They don’t consider the risks to mislabeled patients. They imagine the suggestions they’re making will be done in the best possible way in their own research clinics. They don’t realize that most of psychiatry is being practiced in primary care. So they’re pure at heart but they’re remarkably naive.

MJ: In recent years, thanks to the work of researchers at Dartmouth and journalists like Shannon Brownlee and Atul Gawande, there’s been a blossoming of awareness about overtreatment in general medicine, and how doctors are susceptible to it even though they may think they aren’t. How does any of this apply to the psychiatric community?

AF: Psychiatry got on the bandwagon just as the band stopped playing. Part of the justification for these diagnoses that otherwise made no sense at all is, “We’re going to be like the rest of medicine. We going to diagnose you early and do preventative treatment to prevent the birth of illness,” just at the time when the rest of medicine was realizing that that was, with a few isolated exceptions, causing more harm than good.

MJ: How is DSM-5 worse than DSM-IV?

AF: With DSM-IV, we were determined to be as modest as possible in ambition and as careful as possible in methodology. We had a very high threshold for change; people had to jump through hoops to convince us. And we rejected 92 of 94 proposed diagnoses. We told the experts, “You’re not going to get anything in here unless the data grabs you by the throat.”

MJ: And DSM-5?

AF: They were ambitious. They started out with a grand design to introduce biology into psychiatry, and it was way premature. When that ambition was frustrated, they went to the idea of introducing milder disorders, within the boundaries of normal, because this would be preventative psychiatry. They gave the experts free rein. They said, “This is a blank check.” They way they put it is, “Everything’s on the table.”

MJ: Who are these “experts”?

AF: Well-meaning researchers in a given area who know everything about that area but nothing about how [their recommendations] will be misused in the real world.

MJ: What’s your position on the NIMH debacle?

AF: The problem is that both the American Psychiatric Association and the NIMH have lost sight of what really matters, which is taking care of patients. The APA, in pushing these new categories, is going to divert attention and resources from the people who really need it: the truly ill. And the NIMH, by renouncing current psychiatric systems without having any promising alternative—it must be going after the Obama research dollars that have been suggested to Congress for brain mapping—is disparaging current psychiatric care. I think it’s dangerous and harmful to patients who may lose faith, stop their medicine, and get really sick. We have to get back to treating patients. We can’t wait for brain-mapping and the future, because the brain is the most complicated thing in the universe, and it reveals its secrets very slowly. There are going to be no breakthrough answers.

MJ: So what do we do with DSM-5?

AF: You don’t buy it. You don’t use it. You don’t teach it. There’s nothing official about it.

MJ: But how can you roll it back to the DSM-IV?

AF: I don’t think DSM-IV is perfect. I’m actually not the slightest bit proud of it. At the time, we thought we had done a pretty good job of containing diagnostic inflation, but subsequent events proved that we didn’t. Three years after the publication of DSM-IV, the drug companies wangled Washington for the right to advertise to consumers. We’re the only country in the world that allows that aside from New Zealand. And so they’ve been given this tremendous power to influence the rhetoric and actually to Shanghai psychiatric care.

I think the answer at this point is that everyone should be well informed. Nobody should lose faith in psychiatric treatment, because it’s been shown to be very effective for the people who need it. If you’re a patient, you should know a lot and ask lots of questions and make sure you get sensible answers. No one should ever accept a diagnosis or a medication after a seven-minute session. It’s better to watch and wait, unless the problem is really severe.

MJ: Do you think we can expect any further backlash against diagnostic inflation?

AF: It’s a David and Goliath issue. However, the DSM-5, the NIMH response to it, and the fact that pharma has so far overshot—if 20 percent of teenage boys get a diagnosis of ADD and 10 percent are on medication! The top-selling drugs in the country are antipsychotics and antidepressants and stimulants. We’re spending a fortune on treating kids who don’t have ADD with drugs rather than taking care of the schools.

I think the best hope is the example of tobacco. They were all-powerful 25 years ago and they’ve been trimmed down to size. It’s important that the diagnostic system be taken away from the American Psychiatric Association. It needs to be in safer hands—something like an FDA equivalent—because new diagnoses can be as dangerous as new drugs. And pharma should not be allowed to advertise, just as tobacco isn’t allowed to advertise. There’s also a huge problem in the insurance industry: A doctor doesn’t get paid unless he makes a diagnosis on the first visit. Doctors should be paid for five sessions of evaluation. That would be much better for patients and much cheaper in the long run, because once you get a diagnosis, you may get a lifetime treatment.

The 11 Most Harmful Changes in DSM-5

(According to psychiatrist Allen Frances)

1. Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder: DSM-5 turns temper tantrums into a mental disorder—a puzzling decision based on the work of only one research group.

2. Normal grief will become Major Depressive Disorder, thus medicalizing and trivializing our expectable and necessary emotional reactions to the loss of a loved one.

3. The forgetfulness of old age will now be misdiagnosed as Minor Neurocognitive Disorder, creating a huge false positive population of people who are not at special risk for dementia.

4. DSM-5 will likely trigger a fad of Adult Attention Deficit Disorder, contributing to the already large illegal secondary market in diverted prescription drugs.

5. Excessive eating 12 times in three months is no longer just a manifestation of gluttony. Now it’s a psychiatric illness called Binge Eating Disorder.

6. Changes in the definition of autism will result in lowered rates—10 percent according to estimates by the DSM-5 work group, perhaps 50 percent according to outside research groups. This may be seen as beneficial, but advocates fear a disruption in needed school services.

7. First-time substance abusers will be lumped in by definition with hardcore addicts, despite their very different treatment needs.

8. DSM-5 creates a slippery slope by introducing the concept of behavioral addictions that eventually can spread to make a mental disorder of everything we like to do a lot.

9. DSM-5 obscures the already fuzzy boundary between Generalized Anxiety Disorder and the worries of everyday life. Small changes in definition can create millions of anxious new “patients.”

10. DSM-5 opens the gate further to the existing problem of misdiagnosis of PTSD in forensic settings.

11. Somatic Symptom Disorder makes worrying about your medical illness a psychiatric problem. It would affect 25 percent of chronic pain patients and 15 percent of cancer patients, who may be stigmatized as a result.

The first 10 items are excerpted from a list Frances put together previously for Psychology Today.