UNH Photo Services

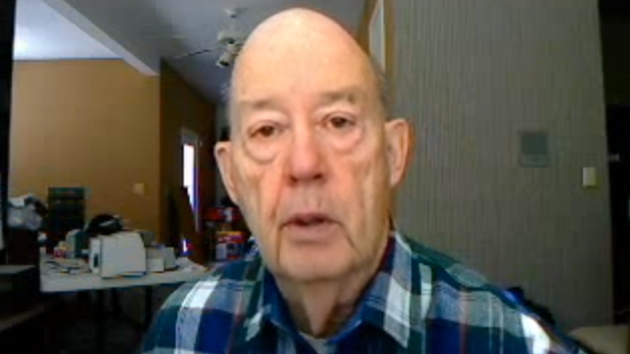

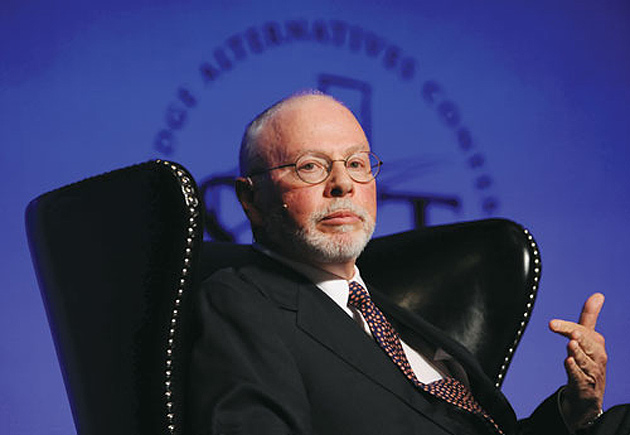

If New Hampshire Republican Dan Innis wins his congressional race, he knows where to send the fruit basket: to the home of mortgage giant Peter T. Paul.

Before running for Congress, Innis served as dean of the University of New Hampshire’s business school, which was renamed for Paul after he donated $25 million. His campaign website touts major building projects he oversaw as dean—projects financed by Paul’s contribution. And Innis’ congressional run is getting a big-time boost from a brand new super-PAC founded and financed by Paul.

“Dan’s a friend,” says Paul, who lives in California. Paul is an alumnus of the University of New Hampshire, and he met Innis through his UNH philanthropy. “He’s the better candidate. He needs to get known.”

Innis, who is one of four candidates running in the Republican primary on September 9 to challenge Democratic Rep. Carol Shea Porter, is socially liberal and favors shrinking the government—exactly the type of politician Paul says he would like to see in Congress. In order to make that happen, Paul created a super-PAC, New Hampshire Priorities PAC, and financed it with $562,000. So far, $376,000 of that has gone into radio and TV ads supporting his friend. Innis himself has raised a little more than $338,000—about $150,000 less than his closest Republican opponent. With Paul in the mix, Innis is head and shoulders over his GOP competitors.

But Paul’s support is somewhat controversial. Paul made his millions as a mortgage wholesaler—a middleman who sells mortgages to homeowners and then sells the homeowner’s application for a loan to the bank or lender that will underwrite the loan. Mortgage wholesalers don’t set the terms of a loan—but they aren’t obligated to get a homeowner the best rate. Wholesalers, many argue, helped fuel the housing bubble because they work on commission and face incentives to push as many mortgages as possible. Paul in particular spearheaded the use of Alt-A loans—a marginally less risky cousin of subprime loans, which require sparse documentation to obtain. These loans helped inflate the real estate market in 2004 and 2005. And Paul is credited with helping spread easy credit to Americans by pioneering new ways to package mortgage debt for investors. When he closed his company, Paul Financial, at the height of the housing crisis, his firm held $3.1 billion in total loan applications.

Armed with these facts, Democrats have tied Paul to the financial crash in 2008. “Paul helped push us to the financial edge,” fumed Arnie Arnesen, a liberal talk radio host in New Hampshire.

But Paul stresses that he didn’t sell subprime loans. He describes himself as more of a go-between who merely peddled the kinds of loans requested by banks. It was banks, he says, who bore the burden of making sure they sold a responsible product.

“What am I to do?” he says. “I make stuff to specifications. If they say, ‘I want a purple shirt,’ it’s an awful color, but we say, ‘Sell it to them.’ We don’t make judgments.”

“There’s plenty of blame to go around” for the crash, Paul adds. But as a mortgage banker, he says, “you either lent by the standards set by larger entities up the food chain, or you exited the business.”

But Paul may be downplaying his role in peddling risky mortgages. In 1998, he sold a company he founded in the late 1980s, Headlands Mortgage, to GreenPoint. The sale made GreenPoint a lending behemoth. It went on to be one of the largest subprime lenders in the country.

Paul says was pushed out of day-to-day operations before GreenPoint became heavily involved with subprime lending. “Basically, I had a little company. I made a couple hundred million dollars,” he says. “And then I sold it, and later, the company that I sold it to had lawsuits.”

A reporter for New Hampshire Business Review dug up Securities and Exchange Commission documents showing Paul left in the summer of 2003, around the time GreenPoint was getting into the subprime game. But Paul stuck around long enough to conceive of some dubious GreenPoint products. In a recent conversation with Paul, the New Hampshire Business Review reporter brought up a 1999 press release in which Paul announced GreenPoint’s new 103 percent mortgage. The product lent borrowers more than the value of the home they planned to buy. “It may sound very horrendous, but it was maybe a tenth of one percent of what we did,” Paul told the reporter. “I probably put slick literature out, because you know, it had sex.”

After resigning from GreenPoint in 2003, Paul started Paul Financial. A 2007 class action lawsuit accused the company of flouting the Truth in Lending Act. The lawsuit paints a picture of Paul Financial as a typical predatory lender, claiming that the company signed-up unwitting borrowers for adjustable rate mortgages that started at a 1 or 2 percent interest rate but shot up after just a few months.

The lawsuit also alleged that Paul Financial gave borrowers repayment plans that resulted in negative amortization—when a borrower pays off less of the total interest owed that month, leading the interest he owes to balloon while the price of his home stays put. Negative amortization was a prime tool utilized during the housing crisis by mortgage bankers looking to loan to individuals who probably couldn’t afford to be homeowners.

Paul Financial closed its door during the housing crisis, before the lawsuit could settle. The Royal Bank of Scotland, which held the loan debt after Paul Financial closed, settled the lawsuit for $1.75 million in late 2013.

“Of course some of the loans went down,” Paul says, when I ask about the lawsuit. “Not many.” Overall, he says, the lawsuits targeted a small portion of loans made by his company.

Tough times followed the crash. Shortly after closing his business, Paul had to fulfill the $25 million pledge he made to the University of New Hampshire. It “hurt a little bit,” Paul told the New Hampshire Business Review. But Paul is back on his feet now with a new business, Headlands Asset Management, for which he teamed up with a Bear Stearns refugee to buy distressed home loans, fix them, and flip them.

Paul is party of the new breed of political donors that have risen up in the wake of Citizens United v. FEC who are dropping money bombs into individual races rather than spreading their wealth around. In 2013, John Jordan, a roguish California vintner, spent $1.4 million on Gabriel Gomez’s failed bid for the Senate in a Massachusetts special election. This year, an Oklahoma mother spent more than $225,000 supporting her 27-year-old son’s failed campaign for Congress. In her bid for Senate, Oregon GOP candidate Monica Wehby has received the support of a super-PAC primarily funded by two people: a Las Vegas sex hypnotherapist and her ex-boyfriend.

Paul is an especially hands-on donor, who approves the super-PAC’s budget for new ad campaigns and signs off on the finished product. “I’m putting money into it, so I pay attention.” New Hampshire Priorities announced at its founding that it would spend about $500,000 before the September primary. (American Unity PAC, a group started by hedge fund billionaire Paul Singer to encourage the GOP to embrace same-sex marriage, has donated $65,000 to the PAC.) “Maybe I’ll do another $100,000 or $200,000,” Paul says. “If it looks like it’ll be effective, I’ll probably just spend it.”

Shea-Porter and Innis’ campaigns did not respond to requests for comment.

“I like the scale of New Hampshire,” Paul adds. “It’s much more manageable.”

Innis’ most serious competition is former congressman Frank Guinta, who defeated Shea-Porter in 2010. Shea-Porter regained her seat in the next election. Given Guinta’s name recognition in the district, Paul hopes his contributions will help get Innis’ name out there. If Innis wins, Paul is open to spending in the general election, too. But he has set a ceiling on what he will spend on this race overall.

“It won’t be more than one,” he tells me.

Meaning $1 million?

“Yes.”