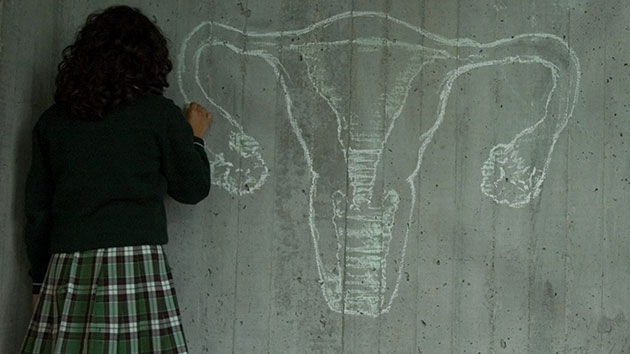

A reproductive health class in Bogotá, Colombia. Joana Toro/ZUMA

People in the United States have been going to Planned Parenthood for nearly a century, ever since Margaret Sanger opened her first birth control clinic in Brooklyn in 1916. But it wasn’t until 1977, after the US had already celebrated Roe v. Wade, that Colombian women had any equivalent organization to turn to. That was the year Dr. Jorge Villarreal started Oriéntame, a women’s reproductive health clinic now credited with inspiring more than 600 outposts across Latin America “and for reshaping abortion politics across the continent,” writes Joshua Lang in a story about the Villarreal family, out today in California Sunday.

Jorge Villarreal Mejía graduated from medical school in 1952 and soon took the reigns of the obstetrics department at Colombia’s national university. During that time, botched abortions caused nearly 40 percent of the country’s maternal deaths. “Women in slum areas were putting the sonda (catheter) inside of them without any sonography,” his daughter Cristina Villarreal told Lang. “They used ganchas de ropa (coat hangers), anything.” When these women showed up at general hospitals, they were shamed and quickly given basic medical attention at most.

So in 1977, Jorge opened a stand-alone health clinic in Bogotá called Oriéntame. Abortions were illegal, so Oriéntame had to focus on helping women who were already suffering from bad abortion attempts, or “incomplete abortions.” Colombians had to wait another thirty years before their mostly Catholic country legalized abortion, under pressure from a coalition that included Cristina Villarreal. (Abortion is now legal in Colombia when a mother’s physical or emotional health is in danger.) In the meantime, Oriéntame continued its mission to heal and empower women, using a sliding-scale payment model in order to reach poorer clients. In 1994, Cristina assumed leadership of the organization, which had grown to include a second nonprofit to help doctors around Latin America open their own Oriéntame clinics.

Lang’s story, an eye-opening and educational read, details the Villarreals’ persistence in the face of police and priests, health administration raids, legal battles, money troubles, and social stigma. Not unlike the volatile abortion politics in the US, across Latin America, writes Lang, “for every political action, there seems to be an equal but opposite reaction,” making Oriéntame’s success “all the more unlikely.” Today, the organization continues to struggle for funding. But fortunately for the estimated 4.5 million women seeking abortions every year across Latin America, and countless others looking for reproductive guidance, Oriéntame’s network has already laced together a much-needed safety net that will be difficult to undo.