<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-250933261/stock-photo-gas-station-attendant-at-work.html?src=bpKmu65IxIM2LsWGe0Zrlw-1-2">Minerva Studio</a>/Shutterstock

In his State of the Union address this week, President Barack Obama gave an approving nod to the price of oil, which is now the lowest it has been in more than a decade.

“Gas under two bucks a gallon ain’t bad, either,” he said.

For motorists, that logic is unassailable. But depending on where in the country you live, the low oil price could come back to haunt you in unexpected ways. According to new federal data, half a dozen states with prominent oil drilling industries have taken heavy blows to their budgets. That could prompt a sweep of spending reductions and cuts to education, poverty programs, and other social services.

“It could be hugely problematic for some of these states,” said Michael Leachman, director of state fiscal research at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

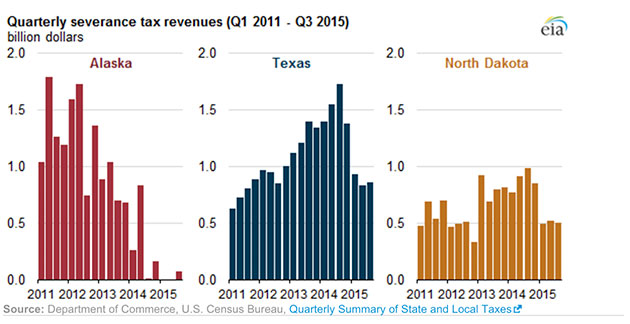

The data show a steep drop in revenue from severance taxes, which natural resource companies pay to states when they extract oil, coal, or natural gas. When oil prices drop, oil production drops next, followed by severance tax revenue. And for states such as Alaska, Wyoming, and North Dakota, which draw a majority of their income from severance taxes, that means the budget can quickly implode. Now, policymakers in those states are scrambling to make up the shortfall in other ways and decide which state programs could face the chopping block.

Alaska’s decline in revenue has been especially severe:

The Energy Information Administration report notes that Alaska’s severance tax income—which provides three-quarters of the state’s budget—went from $5 billion in 2012 to practically zero in 2015. As the New York Times reported, that drop has the state’s governor considering re-instating an income tax for the first time in 35 years. Meanwhile, legislators in North Dakota are considering cutting $100 million in spending after tax revenues came in nearly 10 percent lower than expected. Even though oil production there hasn’t changed much, the EIA found that “total severance tax revenues fell from more than $3.5 billion in 2014 to $2 billion in 2015 as oil prices declined.”

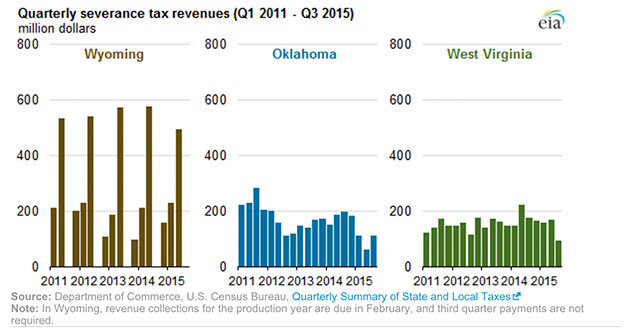

A similar story is playing out in Oklahoma, where, the EIA notes, “collections from state sales taxes and individual and corporate income taxes are also significantly affected by oil and natural gas prices”:

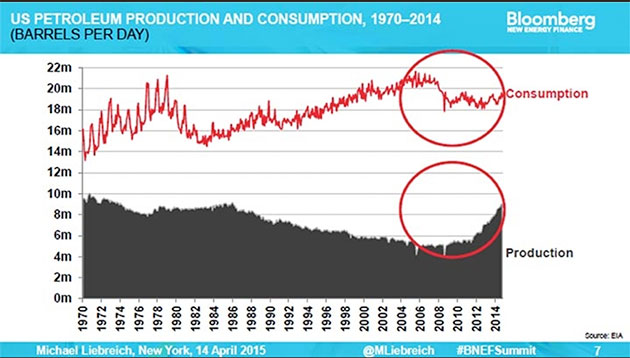

Trying to predict oil prices far out into the future is a fool’s errand, so it’s hard to say how lasting the damage to these states could be. Still, there’s reason to think that the oil market is in for a bumpy road ahead, thanks to a growing market for electric vehicles, increasing fuel efficiency standards, and high volumes of oil coming out of Saudi Arabia and other OPEC countries. According to Bloomberg, oil demand in the US is flatlining even as nationwide oil production increases:

The current tax crisis could signal an urgent need for oil-reliant states to diversify their tax base, Leachman said.

“There’s no question it’s not sustainable in Alaska,” he said. Other states are at risk of following suit. “You’re going to have to rethink your strategy for funding public services if you think oil and gas prices are going to stay really low levels.”