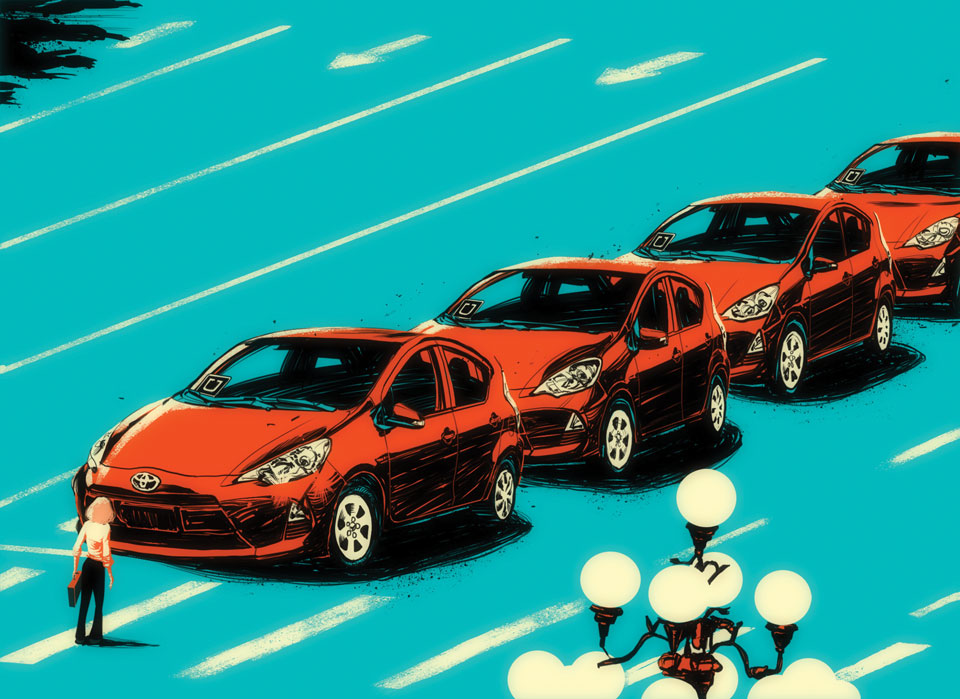

<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-314177504/stock-photo-new-york-us-august-uber-car-service-on-the-streets-of-new-york.html?src=TnXietmkXLMcrVrFiWgrFg-1-0">MikeDotta</a>/Shutterstock

For any Uber user waiting for a pickup in Kalamazoo, Michigan, on Saturday night, Jason Brian Dalton and his Chevy SUV would have looked like a safe ride across town. Dalton, a 45-year-old insurance adjustor, had racked up an average passenger rating of 4.73 stars out of 5 in a month of driving for the ride-sharing service. His reviews, Uber officials say, were favorable.

But shortly after midnight, Dalton was arrested following what police describe as a five-hour “random” shooting spree across Kalamazoo, leaving six people dead and others injured. On Monday, he was charged with six counts of murder, two counts of assault with intent to murder, and eight weapons offenses.

Although Uber chief security officer Joe Sullivan said Monday there was no way to have predicted the violence (Dalton, according to Kalamazoo Public Safety Chief Jeff Hadley, had no criminal record), the incident has drawn new attention to how the company claims to keep riders safe before, during, and after they climb into one of its drivers’ vehicles.

Before the ride: Uber screens new drivers by putting them through a background check process, looking for a criminal record or motor vehicle violations. When someone applies to be a driver, Uber collects the applicant’s personal data, including their full name, address, Social Security number, vehicle registration, insurance, and a copy of their driver’s license, Sullivan wrote on Uber’s website last July. That information is then sent to a third-party background check company called Checkr. According to Sullivan, the company uses the applicant’s Social Security number to gather information on any associated addresses in the past seven years—the maximum permitted under California law—then checks local, state, and national databases for criminal and sex offense records.

If a potential match turns up, a Checkr employee reviews documents in person or online to verify that there was a felony conviction. Uber also checks each applicant’s motor vehicle registration file. Applicants can be disqualified for DUIs, violent crime, misdemeanor theft, or a host of other offenses.

These databases aren’t perfect, and if the person registers to drive using a fraudulent Social Security number, Uber admits that its background check won’t pick up on the discrepancy since the company does not collect fingerprints. Two weeks ago, Uber agreed to settle two class-action lawsuits in which customers alleged that the company falsely called its background checks “industry-leading,” despite not using a national fingerprint identification system. Uber—which maintains that background checks using fingerprints are faulty and discriminate against people who were arrested but never charged—”expressly denied the allegations” but settled for $28.5 million.

During a press call Monday, Uber officials repeatedly stressed the limitations of the background check system in the Kalamazoo case, given the suspect’s clean criminal record. “If there’s nothing on someone’s record, then no background check is going to raise a flag,” Sullivan told reporters.

During the ride: In the event of an emergency during an Uber ride, passengers have few options to keep themselves safe—one of the reasons the company has drawn criticism for numerous reports of crimes, including sexual violence, committed during rides over the past few years. Passengers can send details of their trip to contacts, but there is no obvious, built-in way to contact the company or law enforcement in the midst of a dangerous ride.

Last February, Uber officials told reporters that the company intended to roll out an “SOS button” or “panic button” in US cities that riders could tap to alert police if they felt threatened. The feature, which the company introduced in India last spring after a woman alleged that she was raped by an Uber driver, immediately connects a rider to law enforcement and sends GPS data with the vehicle’s exact location to a local police control room.

But on Monday, Sullivan walked back the idea of implementing the panic button in the United States. “In the United States, 911 is the panic button,” he said. “It’s the panic button that law enforcement wants people to use, and we don’t want to try and replace that.”

Mike Mellen, a Kalamazoo resident who rode with Dalton just before the the shootings on Saturday night, told local news station WWMT that Dalton was driving erratically and wouldn’t stop the car. When he got a chance, Mellen said, he jumped out.

“We were kind of driving through medians, driving through the lawn, speeding along, and then, finally, once he came to a stop, I jumped out of the car and ran away,” Mellen said.

After the ride: Shortly after jumping out of Dalton’s car, Mellen called police. He and his fiancée sent Uber a lengthy email about the ride after struggling to figure out the best way to alert the company, according to the Washington Post. Mellen’s fiancée also posted details about the trip on Facebook to warn other local riders:

Uber driver Jason Dalton’s last rider posted about his behavior just prior to deadly rampage. #KalamazooShooting pic.twitter.com/jByBa7JU4B

— Robb Ware (@robbware) February 21, 2016

After every ride, Uber passengers are prompted to rate their driver out of five stars and add comments. Sullivan said these reviews and follow-up questions are used to suspend drivers who rack up multiple poor ratings. Still, it’s unlikely that one single-star review is enough to alert an Uber employee to an emergency situation. A better option for reporting an incident is the company’s “Critical Safety Response Line,” an 800 number connecting users to Uber’s US-based emergency response teams, though users have to go digging through the app to find instructions on using it. Otherwise, as Mellen discovered, there’s an email address.

When Uber receives a complaint about a driver, Sullivan said, the company takes one of two actions. If the passenger reports violence, the service immediately suspends the driver while it investigates. If the report is for “bad driving,” Sullivan says, Uber will try to get both sides of the story before suspending a driver’s account: “We’ll typically wait to try to talk to the driver or try to collect more information, especially if they’re receiving favorable feedback rides in context to that bad rating. The reality is, when drivers drive for hundreds of rides, they will sometimes receive negative feedback, and we don’t want to overreact.”

It’s unclear how the company classifies “violence” or how quickly Uber responds to customer reports, given that Dalton continued taking fares for hours following Mellen’s ride. The company is currently testing a feature that would allow it to corroborate rider feedback using GPS data, but that service is available only in Houston.

Uber has already provided GPS data to law enforcement and is cooperating with the police investigation, Sullivan said. In the meantime, the company does not plan on changing its screening process for new drivers.

“A background check is just that—a background check. It does not foresee the future,” Ed Davis, a member of Uber’s safety advisory board, said on Monday. “After an incident like this, we all struggle for answers.”