John Locher/AP

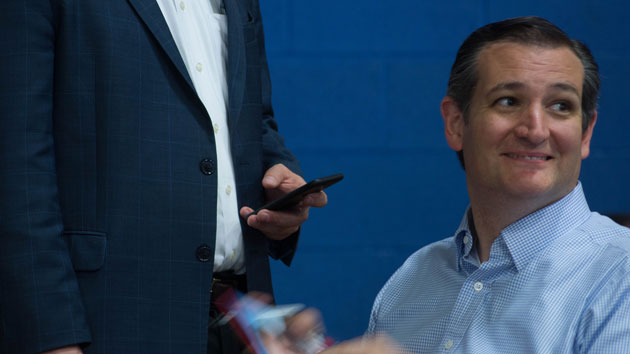

It’s finally all coming together for Ted Cruz. It just might be too late.

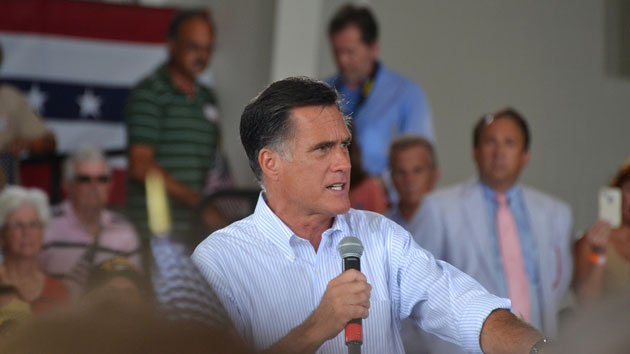

High-profile Republicans who haven’t always counted themselves fans of the senator from Texas have begun lining up behind his campaign. Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), who recently described Senate Republicans’ dislike of Cruz through the lens of a hypothetical assassination, is now rallying behind him as the best person to stop Donald Trump from becoming the Republican nominee. Mitt Romney announced he would vote for Cruz and encouraged fellow Republicans to follow his lead in order to stop “Trumpism.” The #NeverTrump movement has spent millions, with millions more on the way, to wound Trump so that Cruz can defeat him.

The Republican establishment is finally rallying around a Trump alternative, just as Cruz’s path to the nomination is becoming almost impossibly narrow.

Cruz’s campaign is well organized, well funded, and committed to a delegate-based strategy to steal the nomination from Trump at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland in July. It may triumph in a few more states, beginning with an expected victory Tuesday in Utah. And yet, as Larry Sabato, who runs the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics, puts it, “Everything has to go perfectly for this to work.”

Barring a catastrophic plunge in Trump’s popularity, Cruz cannot make up his delegate deficit—Cruz has 410 to Trump’s 673—and reach the 1,237 delegates needed to clinch the nomination outright. Instead, Cruz’s only real shot at the nomination is to pick off enough delegates to prevent Trump from amassing a majority and force a contested convention, where his campaign’s hard work wooing and recruiting loyal delegates will pay off on the convention floor.

Cruz’s big problem is winner-take-all states, where he would have to beat Trump to rack up any delegates. So Cruz and his allies in the anti-Trump movement are expected to focus on the states that allot delegates by a proportional method—either by vote share or by congressional district.

Cruz’s path to a contested convention begins on Tuesday in Utah, where he has the endorsement of one of the state’s two senators, Mike Lee, and where Trump is not very popular with the large Mormon population. The next big state for Cruz is Wisconsin, which holds its primary on April 5. The two most recent polls there, taken in February, show Trump up by 10 points and 6 points. It’s not an insurmountable lead, and Wisconsin gives three delegates to the winner of each of its eight congressional districts, meaning Cruz could pick off a few without winning the whole state.

The largest remaining states, New York on April 19 and California on June 7, assign delegates by congressional district, a method that could allow Cruz to slow Trump’s march to 1,237. Cruz has a shot in three other primaries on June 7: in New Mexico, which awards its delegates proportionally, and in Montana and South Dakota, which are winner-take-all states.

But there are substantial hurdles to Cruz’s strategy. One is named John Kasich, who himself is hoping to capture the nomination at a contested convention and therefore has little incentive to drop out before the end. “I think the fragmentation of the field [is] what’s always been what’s propelling Trump,” says Scott Jennings, a GOP consultant in Kentucky who formerly worked alongside Karl Rove in the George W. Bush White House, and who backed Jeb Bush until he dropped out in February. As long as the contest remains divided among Trump, Cruz, and Kasich, Jennings says, Trump is “going to keep raking up delegates.”

If Cruz can neutralize the Kasich factor and pull off a flawless delegate-based strategy over the next two and a half months to deprive Trump of a delegate majority, his next step will be to consolidate his support among the delegates who are committed to voting for Trump on the first ballot. That would allow him to surpass Trump after the first round of voting at the convention, when some delegates initially bound to Trump or to one of the candidates who has dropped out, such as Marco Rubio, can choose to vote for Cruz. The process of wooing delegates and placing friendly faces in each state’s delegation is long and complicated, but the Cruz campaign is better organized than the Trump campaign to manipulate this process.

“‘Picking them off” is a good way to put it,” says Sabato. “It’s not just winning states and caucuses and primaries, it’s knowing the rules well and working with state and local party leaders who are appalled by Trump to get additional delegates.”

Even if Cruz, whose strategy thus far has been foiled by Trump, manages to pull off the perfect convention coup, he could be crippled as a candidate by a backlash from Trump supporters. This is why some party insiders believe that for Cruz to be successful, he not only needs to stop Trump from reaching 1,237; he needs to stay close enough in the delegate count to justify taking the nomination at the convention.

“They have to stop [Trump] from being close,” says Sabato. “If he’s 50 or even 100 delegates short,” it would be hard to justify giving the nomination to Cruz or Kasich. If Trump has the most delegates, he will claim that an effort to subvert him on the convention floor goes against the will of the people. In fact, he’s already making a version of this argument. To combat that claim, Cruz would need to be close behind Trump in the delegate count. “The thing for Cruz is, even if he doesn’t get to 1,237, if he hopes to do the contested convention, then getting as close to equivalent to Trump is really important for PR reasons,” Jennings says.

Not everyone agrees. “If he doesn’t have 1,237, he doesn’t have 1,237—that’s the end of the story,” says Rick Shaftan, a Cruz supporter who is advising a super-PAC working to elect the senator. “If he doesn’t have those delegates on the second ballot, he didn’t run a good campaign, did he?”

But that logic could be a hard sell for Trump’s supporters, particularly if Trump enters the convention with a significant delegate lead. Awarding the nomination to Cruz at the convention would likely invite blowback and even defection from many Republican voters, a reality that could doom the party in November.

Sabato believes party leaders are fully aware of that possibility as they work to defeat Trump. They know they could be courting defeat in the general election, he says, but consider it more important to stop Trump from becoming the nominee. “They’re basically trying to, quote-unquote, save the Republican Party while sinking the Republican Party,” Sabato says. “It’s ‘heads you lose, tails you lose.'”