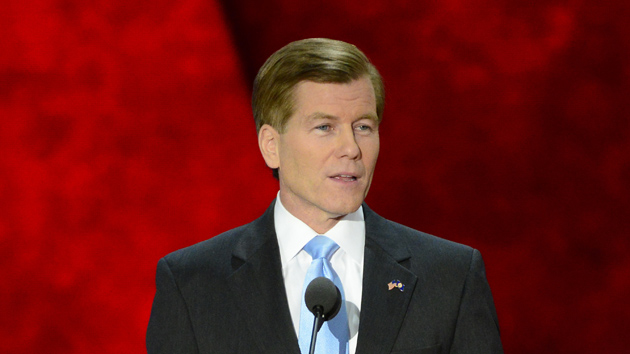

Former Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell during his corruption trial in 2014AP/Steve Helber

The Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United, which overturned restrictions on corporate and union campaign contributions, has been blamed for a lot of things: a flood of “ads that pull our politics into the gutter” (per President Barack Obama), the increased power of billionaires in politics, and even the rise of Donald Trump. This year, critics might be able to add another item to that list: keeping disgraced former Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell out of prison.

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in the criminal case against the former rising star of the Republican Party. In January 2015, a federal judge sentenced McDonnell to two years in prison on corruption charges, stemming from his acceptance of loans and gifts from a political supporter. McDonnell is now fighting the sentence before the Supreme Court. The former governor argues that the charges against him should be thrown out, pointing to the court’s ruling in Citizens United where the court’s majority rejected the notion that political favors are always equivalent to criminal corruption. If the court agrees with McDonnell, prosecutors might have a more difficult time going after public corruption in the future.

Here are the facts of the case. When McDonnell took office in 2010, he and his wife were in deep financial trouble, in large part because of bad real estate investments. He owed credit card companies nearly $75,000 and was losing money on rental properties he owned with his sister in Virginia Beach that were mortgaged to the hilt. He’d borrowed $160,000 from friends and family to stay afloat.

The McDonnells found a savior in Virginia businessman Jonnie Williams Sr., who owned a dietary-supplement company that made a tobacco-based supplement called Anatabloc that could supposedly cure everything from arthritis to multiple sclerosis. Williams hoped to get McDonnell’s help in persuading state universities to conduct clinical trials on Anatabloc so it could get FDA approval as a more lucrative prescription drug. Williams lent McDonnell his private plane to travel to a California political event and came along for the ride so he could try to convince the governor to assist him.

That fateful meeting kicked off what the government said was a long-running conspiracy in which the McDonnells asked for and received more than $175,000 in luxury goods, gifts, and loans from Williams. Williams also let McDonnell drive his Ferrari during an expenses-paid weekend at Williams’ vacation home and took McDonnell’s wife, Maureen, on a shopping spree. McDonnell then helped arrange a number of meetings with state officials who might be able to help Williams’ firm persuade state universities to undertake research on Anatabloc.

The McDonnells were indicted in January 2014, and Bob McDonnell was convicted of 11 corruption charges that fall. Among the charges was honest services fraud, a statute that has been in the crosshairs of judges and criminal-defense lawyers for a number of years. The statute, which has been used to prosecute the likes of former Illinois Gov. Rod Blagojevich and media mogul Conrad Black, is vague, simply making it a crime “to deprive another of the intangible right of honest services.” Critics see it as unconstitutionally broad, allowing prosecutors to bring charges against white-collar criminals and politicians for activities that are not well defined.

It was this statute that former Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling successfully challenged in his 2010 Supreme Court case, in which the court significantly narrowed the list of crimes that could be included under the wide-ranging statute. Before his case, lawyers had argued that it turned such innocuous things as calling in sick or going to a baseball game into federal crimes. The high court in Skilling’s case narrowed the parameters and ruled that it could apply only to bribery and kickbacks.

In McDonnell’s case, the corruption charges required proof that he took money and gifts in exchange for performing “official acts” on Williams’ behalf. His lawyers argue that what the government has called “official acts” are indistinguishable from the sorts of things governors do every day in their jobs, including proposing and scheduling meetings, sending emails, and attending luncheons. (They also argue that the money and gifts shouldn’t be considered bribes when Virginia state law allows state politicians to accept unlimited gifts and loans.)

McDonnell argues that nothing he did for Williams met the criteria of the “quid” in the quid pro quo arrangement necessary for a bribery conviction. Indeed, thanks largely to some savvy staffers and state employees who rebuffed Williams’ requests, McDonnell never gave Williams much of anything other than access to a few state officials. The state universities never agreed to clinical trials for Anatabloc, which has since been taken off the market. “This case marks the first time in our history that a public official has been convicted of corruption despite never agreeing to put a thumb on the scales of any government decision,” McDonnell’s brief argues.

McDonnell says that if his conviction is allowed to stand, just about anything an elected official does in the course of his work—like “inviting donors to the White House Christmas Party”—could qualify as an “official act” under the bribery statute. “These laws threaten First Amendment rights by transforming every campaign donor into a potential felon,” McDonnell argues in his brief. “This is a constitutional minefield.”

To support his argument, McDonnell cites Citizens United, in which the court ruled that “ingratiation and access…are not corruption.” The justices were notably skeptical in that case of campaign finance reformers’ arguments that limits on corporate political spending were a necessary defense against corruption, nor did they buy that cozy relationships between donors and politicians were necessarily corrupt. They wrote that campaign contributions “embody a central feature of democracy—that constituents support candidates who share their beliefs and interests and candidates who are elected can be expected to be responsive to those concerns.” McDonnell’s lawyers are clearly hoping to appeal to that sentiment here.

Whether they’ll succeed is an open question. The honest services fraud statute was much hated by the late Justice Antonin Scalia, who was undoubtedly one of the votes in favor of taking up McDonnell’s case in the first place. Without him, much less is certain. Justice Samuel Alito is a former prosecutor whose sympathies may lie with his law enforcement colleagues. As for the rest of the justices, their views are anyone’s guess. While the liberals didn’t sign on to the court majority’s argument in Citizens United that money is not a corrupting force in politics, they did side with Skilling and his contention that the honest services statute was too vague. Liberal icon Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote the majority opinion in that case, in fact.

The government poked a hole in the Citizens United argument by reminding the justices in its brief, “The bribes at issue here were personal payoffs, not campaign contributions.” McDonnell and his wife got more than $175,000 in personal loans and gifts and others freebies from Williams, and the government argues that Ferrari rides and custom golf bags are far different from checks to a campaign fund or a super-PAC. That kind of behavior isn’t just sleazy politics, they say; it’s a criminal offense.