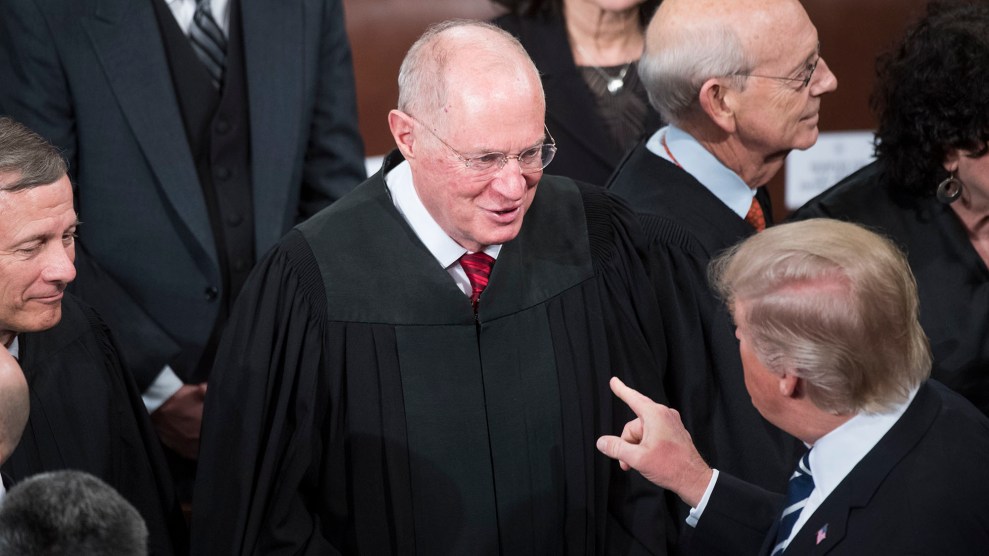

President Donald Trump greets Justice Anthony Kennedy after addressing a joint session of Congress in February.Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call via AP Images)

The Supreme Court will hear a blockbuster case this fall on partisan gerrymandering—one that could begin to close the door on extreme gerrymandering or throw it open wider so that states will feel free to redistrict the opposition party into oblivion.

The case, Gill v. Whitford, comes out of Wisconsin, where the Republican-controlled Legislature in 2011 drew districts that would give Republican an advantage for years to come. In 2012, Republicans lost the popular vote but won 60 of 99 seats in the state Assembly. Voting rights advocates sued, arguing that the partisan gerrymander violated the equal protection and free association rights of Democrats in the state. Last November, a district court agreed, the first ruling against partisan gerrymandering in three decades.

The Supreme Court has previously found partisan gerrymandering constitutional, but Justice Anthony Kennedy—who will likely be he swing vote in this case—has written that gerrymandering can go too far. The Wisconsin case forces the court to decide whether there is a constitutional limit to partisan gerrymandering. Nationwide redistricting in 2020, and all future congressional and state legislature elections, will ultimately hinge on whether the courts will referee extreme gerrymandering.

“This is a historic opportunity to address one of the biggest problems facing our electoral system,” Wendy Weiser, director of the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice, a left-leaning law and policy think tank, said in a statement Monday. “Gerrymandering has become so aggressive, extreme, and effective that there is an urgent need for the Supreme Court to finally step in and set boundaries.”

The lower court had ordered the state to draw new maps by November, to be used in the 2018 elections. But on Monday, the Supreme Court put that on hold until it decides the case—meaning Wisconsin will likely go through at least one more election cycle using its current gerrymandered districts. The hold could be an indication that the court is leaning toward reinstating the gerrymandered maps for good, because justices weigh the likelihood of success when deciding whether to grant stays.

The Wisconsin case sits apart from other racial gerrymandering cases, including several from North Carolina and Texas, by testing the limits of purely partisan redistricting. In the other cases, states have tried to defend lopsided maps that benefit Republicans on the grounds that partisan gerrymandering is a protected right, whereas racial gerrymandering is not. In a decision last month that struck down a racial gerrymander in North Carolina, four Supreme Court justices signed onto a dissent that drew a distinction between racial gerrymandering and partisan gerrymandering, which they wrote is a protected right of states. “[I]f a court mistakes a political gerrymander for a racial gerrymander, it illegitimately invades a traditional domain of state authority, usurping the role of a State’s elected representatives,” Justice Samuel Alito wrote. “This does violence to both the proper role of the Judiciary and the powers reserved to the States under the Constitution.” The dissent sent shivers through the voting rights community, particularly because Kennedy signed on.

In most redistricting cases, including recent cases on racial gerrymandering, the courts largely rely on the Constitution’s equal protection guarantee. But in the Wisconsin case, the district court relied more on the First Amendment’s right to free association. Specifically, the court found that the maps minimized the voting power of Democrats, an unconstitutional form of discrimination based on citizens’ voting history or party affiliation.

Even though Kennedy joined the dissent in the North Carolina case, the First Amendment argument could win him over. Kennedy is known as the court’s strongest defender of First Amendment rights and has hinted that it may be the key to limiting partisan gerrymandering. “The First Amendment may be the more relevant constitutional provision in future cases that allege unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering,” Kennedy wrote in his concurrence in a 2004 redistricting case. “After all, these allegations involve the First Amendment interest of not burdening or penalizing citizens because of their participation in the electoral process, their voting history, their association with a political party, or their expression of political views.”

The outcome of the Wisconsin case will likely depend on whether Kennedy still believes this.