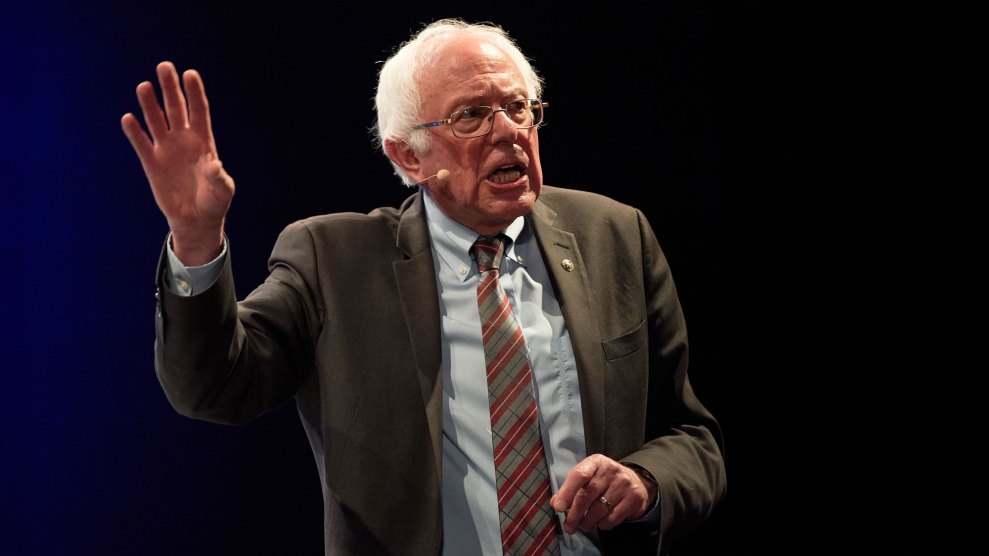

Michael Bowles/Rex Shutterstock via ZUMA Press

When supporters of Bernie Sanders convened the first People’s Summit last year in Chicago, an air of anxious optimism suffused the event. The gathering came days before the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, and the attendees, drawn from the ranks of the candidate’s most passionate supporters, held onto hopes that the independent senator from Vermont might still be on the path to the White House.

He wasn’t, but 12 months later, some 4,000 lefty organizers, activists, campaign vets, candidates, and Sanders himself returned to Chicago for what amounted to a three-day celebration of the movement’s political ascendancy. In speeches, breakout sessions, and interviews, attendees offered a similar refrain: The political revolution is already happening, and it is already remaking the Democratic Party.

Over three days at the sprawling McCormick Center, they huddled in small groups to discuss best practices for organizing, lessons learned from 2016, and how to prevent, er, Bernout. The sessions ranged from trainings on nonviolent resistance (attendees were sequestered in a breakout room where they took turns role-playing as protesters and police) to PowerPoint presentations on neoliberalism and the emerging possibility of “utopia.”

The event was put together by a collection of Sanders-aligned organizations, including the grassroots group People for Bernie, the Democratic Socialists of America, Sanders’ political nonprofit Our Revolution, and the new Sanders Institute, a think tank run by his wife, Jane. The bulk of the funding came from National Nurses United—the union that was instrumental in backing both Sanders’ presidential campaign and the single-payer health care bill that recently passed California’s Senate.

One thing was clear: The diverse movement Sanders assembled last weekend looks far different from the lily-white one that first set out to win Iowa and New Hampshire for him. Attendees submitted applications to take part in the summit, and organizers looked for racial and socioeconomic diversity. “If we had open registration to the general public, it would have looked like a Bernie rally in Wisconsin,” said Winnie Wong, a People for Bernie co-founder who helped organize the summit. Just 46 percent of the 4,000 attendees were white and a third were under 30. There were undocumented Latino students, Oglala Lakota “water protectors,” Black Lives Matter activists, and yes, at least one white factory worker from Wisconsin who once voted for Scott Walker.

The People’s Summit didn’t have the cattle-call quality that has come to define similar events on the right, such as the Conservative Political Action Conference and the Values Voters Summit. Sanders gave a keynote, but only a handful of other elected officials dropped by—and most of them were not household names. They included Rep. Ro Khanna of California, a tech bro turned populist; Chokwe Lumumba, the newly elected mayor of Jackson, Mississippi, who promised to turn his city into “the most radical city on the planet”; and khalid kamau, a member of the Democratic Socialists of America who recently won election to the city council of South Fulton, Georgia (and spells his name without capital letters).

The West Virginia environmental activist running against conservative Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin was there; so was Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s Democratic challenger. You could hardly refill your coffee without meeting someone running for county commissioner.

“Bernie would have won” may have been the mantra of some of the attendees, but many of the organizers took seriously the fact that he ultimately didn’t win, and they wrestled with the mechanics and messaging of a campaign that could.

At a breakout panel on Saturday, Becky Bond, a former senior Sanders aide who helped assemble the campaign’s national field operation, was challenged by an African American attendee about the whiteness of the campaign’s leadership. Bond acknowledged that the homogeneity of the campaign’s top guns had hurt them. She pointed to the recent district attorney’s race in Philadelphia, where Larry Krasner—a defense attorney supported by groups including Our Revolution, the DSA, and Bond’s Big Organizing Project—had won an insurgent victory in the Democratic primary by campaigning on his record opposing police brutality and cash bail.

“Had we done years of that work,” she said of the issues animating the DA’s race, “I think we would have won” the presidential primary.

As it happens, Krasner was holding court about his win a few floors down, at a training session for would-be candidates and campaign workers. Krasner had been opposed by almost every Democratic ward boss in the city, but he ended up winning 44 of 66 wards. He accomplished that by boosting turnout almost by 50 percent over previous municipal races. He even found some voters who hadn’t turned out last fall when Donald Trump won the state. Most of those new Krasner voters were African American.

“The reality that I represented activists and organizers for 25-plus years unquestionably meant that the campaign activated people who are incredibly good at politics but don’t normally do it,” he said, giving a description that also applied to a lot of the people who showed up in Chicago. “That might be the big lesson: All over the country there are networks of activists and organizers who might just be better at politics than the people in politics.”

In Krasner’s view, his race offered a template for similar candidates to succeed. “Candidates of color and white candidates who are able to form that coalition will be unbeatable with their own party,” he said. “And they’ll be unbeatable by any other party.”

The summit represented a very different view of the political landscape than that being discussed by many “Resistance”–minded Democrats. If you got your political news from speakers at the conference, you might not know about the Obamacare repeal bill making its way through the Senate or Democrat Jon Ossoff’s lead in the upcoming Georgia congressional special election. Hardly anyone mentioned Russia, except to say that no one should mention Russia. “We need to keep the focus of our work on our vision, not the latest scandals,” Jane Sanders said. “The hell with Russia!” said Nina Turner, a potential candidate for governor of Ohio, who may have been Bernie’s most popular surrogate at the conference.

You would, on the other hand, be fully up to date on the status of California Senate Bill 562, which would create a single-payer health care plan in the nation’s largest state. And you’d probably know about Christine Pellegrino, a Berniecrat who recently won a special election for a New York state assembly seat in a Trump-voting Long Island district.

British Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn got more mentions onstage than Trump, and he got a special shout-out from Sanders during his keynote. In this context, Corbyn’s surprisingly strong showing in Thursday’s UK election was just a higher-profile version of what Krasner, Lumumba, and kamau had done. In fact, some Bernie veterans had worked on Corbyn’s behalf.

Claire Sandberg, a former Sanders campaign staffer who spoke to a group of organizers Saturday, was fresh off the plane from the United Kingdom, where she spent six weeks working as a strategist for Labour-aligned organizations.* “Everyone here is looking to the UK right now and feeling this wellspring of hope,” she said. The Labour Party defied expectations , she believed, less through innovative campaigning or the raw charisma of Corbyn than through a compelling message, in the form of the Labour Manifesto. It wasn’t too hard to find a Bernie parallel. (It also didn’t hurt that Corbyn’s success had come at the hands of the Democratic elites Sandernistas rail against: Obama 2012 campaign chief Jim Messina helped run the Tory campaign.)

A major aim of the conference was to build a political left that can “transform the Democratic Party,” in Sanders’ words. Organizers persuasively made the case that from California to Mississippi to the halls of Congress, this transformation is already happening. The idea is to take what started as one long-shot campaign and turn it into hundreds or thousands of different ones—some electoral and some not—and build an intersectional movement strong enough to walk on its own without a presidential race to guide it.

But the glue for the weekend, the element that united such diverse groups of lefty organizers, was still Bernie. You could pose next to cardboard cutouts of the senator at booths in the exhibit hall or sign a petition to “Draft Bernie”—part of an effort to coax the senator into running for president again under a new “Justice Party.” People for Bernie, the grassroots group that helped turn a 70-year-old curmudgeon into a millennial icon, offered T-shirts with the senator’s hair and glasses over the phrase “Hindsight is 2020.” The official conference store was filled with Bernie swag. The senator came and went, but Jane Sanders was everywhere.

“He is a global meme,” says Wong, the People for Bernie co-founder who helped organize the summit. “And we have direct access to the global meme, so we should really utilize this moment.” Why mess with what works?

Even the best-run campaigns have a tendency to fade away the further they get from the race in question. (Barack Obama’s Organizing for America famously fizzled out during the 2010 midterms.) But Sanders’ army is very much alive. When one of his closest allies, National Nurses United executive director Rose Ann Demoro, referred to Sanders at a pep-rally-style Friday event as “our real president,” chants of “Bernie would have won!” broke out in the crowd.

Sanders has expressed frustration with questions about his future prospects, but at the People’s Summit the speculation was coming from inside the room. He was interrupted repeatedly by supporters shouting “Draft Bernie!” and clutching signs from the Justice Party booth. His hourlong address was part stump speech and part manifesto. He rattled off a list of movement-backed candidates (many of them Sanders delegates) who had won local elections since November, and he outlined a platform and message by which he—or someone like him—might effectively run against a faux-populist bomb-thrower.

When it was over, he gave the microphone back to Demoro. “I want to say to the Draft Bernie people: I’m with you,” she said.

Bernie and Jane Sanders smiled awkwardly, and Demoro shrugged. “Heroes aren’t made,” she said. “They’re cornered.”

*Correction: This article originally misstated the nature of Sandberg’s work in the UK.