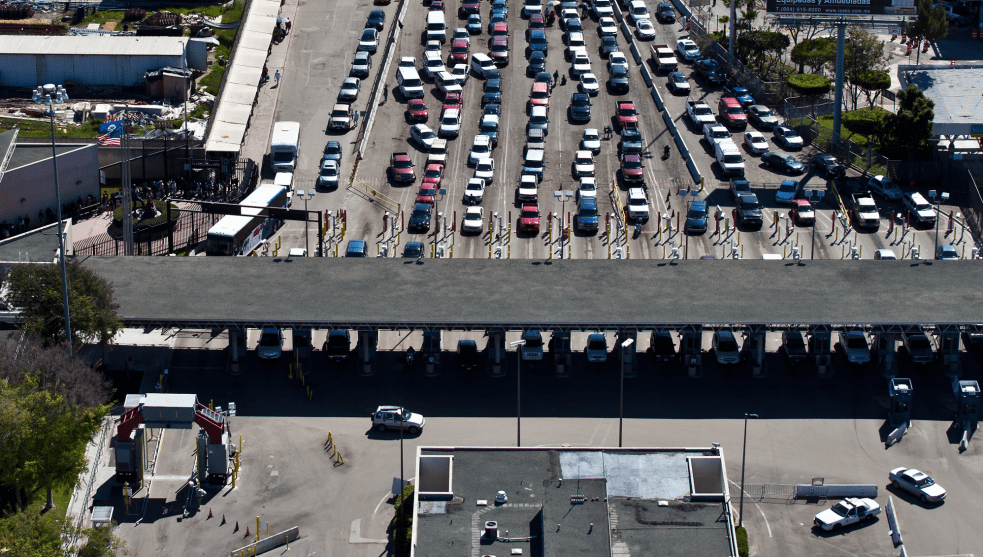

Traffic at the Otay Mesa border crossing in San Diego.Josh Denmark/US Customs and Border Protection

In August 2016, Dinora Doe and her now-18-year old daughter arrived at the Otay Mesa border crossing in San Diego fleeing death threats, kidnapping, and rape committed by MS-13, a gang that has terrorized citizens in Doe’s native Honduras.

On their first two attempts to enter the United States, both women were told (incorrectly) that Central Americans were not eligible for asylum, according to a court document. On their third attempt, a US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) official told Dinora she could cross, but only if she left her daughter behind. They chose to stay in Tijuana instead, where they remain today.

Yesterday, Doe became one of six individual plaintiffs in a class-action lawsuit filed by immigration lawyers and advocates alleging that US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) illegally turned them away after claiming that there was no asylum in the United States.

The lawsuit, which is being argued by the American Immigration Council, the Center for Constitutional Rights, and the law firm of Latham & Watkins, claims that Doe’s case is part of a systematic effort by CBP to prevent people from making asylum claims. In a call with reporters, the lawyers argued that border officials have misled, threatened, and physically abused asylum seekers in hundreds of cases to prevent them from entering the country. These families see the United States as their only refuge, said Baher Azmy, the Center for Constitutional Rights’ legal director.

“Under basic human rights principles, and this country’s stated ideals,” he said, “this country must hear their stories and offer them the protection of the law.”

The lawsuit draws attention to what Azmy described as an “increasingly rogue” CBP. Asylum seekers mentioned in the court filing have been mistakenly told “Donald Trump just signed new laws saying there is no asylum for anyone,” while others were coerced into recanting their fear of returning home on video. (CBP said that it cannot comment on ongoing litigation.)

Many of the families arriving at southern border crossings are Central Americans fleeing persecution from MS-13 and other gangs. After MS-13’s initial death threats, Dinora and her daughter fled to another city before eventually returning home. When they did, the lawsuit states, they were held in captivity by MS-13 for three days and repeatedly raped. Afterwards, they fled to Mexico, but the gang threatened them there, too. It was only then that they set out for the United States.

Azmy said that their experiences at the border violate decades of precedent that began after World War II. In the 1951 Convention on the Rights of Refugees, the international community adopted the principle that no refugees should be sent back to countries where they are likely to face persecution or torture. The United Staes signed on to that convention in 1967. Over the years, it has given people fleeing persecution in countries ranging from China to El Salvador the legal right to make their case before an asylum officer, rather than a border official.

Advocacy groups claim that border officials have increasingly not followed this process. Erika Pinheiro, the policy director at Al Otro Lado said her organization, which is also a plaintiff, has seen greater numbers of people being turned away by border officials because of incorrect claims about US asylum law. Overall, she calls it an “enormous change.”

In January, a CBP spokesman told the Washington Post that there is “zero [evidence] to corroborate any kind of change in tone or guidance or policy” since the election. Yesterday, CPB told Mother Jones that is still the case. The lawsuit, and the fact-finding it leads to, could help to confirm or refute that claim.

After being turned away, the asylum seekers from Mexico and Central America often end up in Mexican border towns where they may be kidnapped, robbed, or even raped, said Kate Shepherd, a legal fellow at the American Immigration Council. The plaintiffs’ lawyers are seeking emergency relief for the individual plaintiffs so that they aren’t left along the border as the case is argued. More broadly, they hope that the class-action suit will stop the alleged illegal refusals and create mechanisms for ensuring that they don’t happen in the future.

In the meantime, Shepherd said asylum seekers will continue to be at risk. “Every day that this practice continues,” she said, “is a day that a legitimate asylum seeker is returned to harm and even death.”