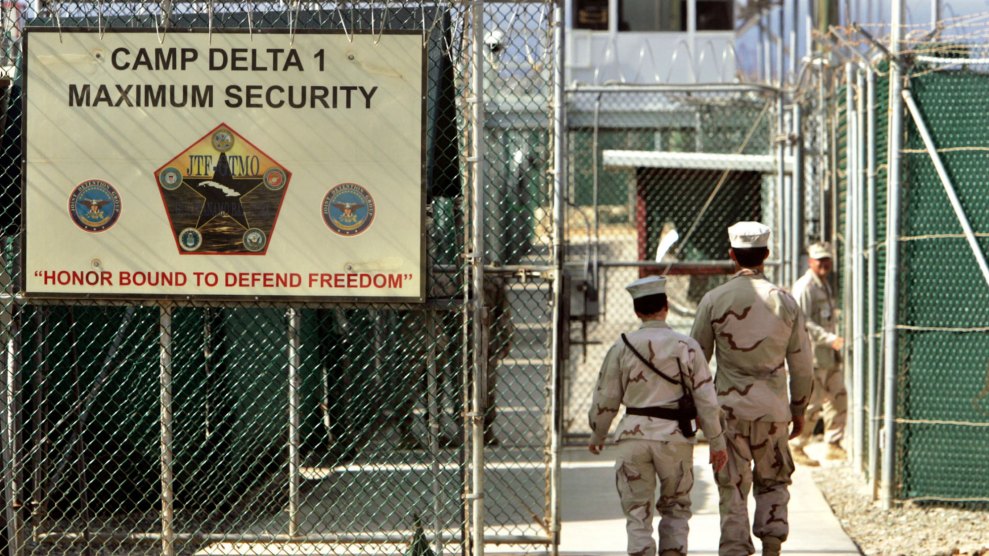

US military guards at the Guantanamo Bay US Naval Base in Cuba.AP Photo/Brennan Linsley

Following Tuesday’s terror attack in Lower Manhattan, President Donald Trump suggested that he might send the suspect, Sayfullo Saipov, to the US naval base at Guantanamo Bay, where the US has been holding alleged terrorists indefinitely, often without charges, for the past 15 years. “We have to get much tougher,” Trump said. “We have to get much smarter. And we have to get much less politically correct. We’re so politically correct that we’re afraid to do anything.” Sens. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) and John McCain (R-Ariz.) piled on, suggesting that not only should Trump declare Saipov an enemy combatant and send him to Guantanamo, but Saipov should be interrogated there without a lawyer. “You could if you wanted to,” Graham said.

But could you? Such a move would be unprecedented. The US government has never sent someone arrested on US soil to Guantanamo. That may be one reason Trump has backpedaled on his initial comments, suggesting that Saipov could get the death penalty more quickly by going through federal court. Graham and McCain, though, are still pushing the administration to declare Saipov an enemy combatant, raising questions about whether Trump even has the authority to dispatch Saipov to the Cuban prison. Here’s why doing so would be constitutionally dubious.

First, Saipov, a citizen of Uzbekistan, was in the United States legally at the time of the attack. As a result, he’s entitled to all the constitutional protections of due process, the Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination, and the right to a lawyer. All of the men who have been sent to Guantanamo were captured on foreign soil and, as a result, don’t have these rights. That’s why many of them have languished there for so long without being charged with a crime. Because he was captured inside the United States, Saipov couldn’t be tried by a military tribunal, as other Guantanamo detainees have been, because the law authorizing those proceedings don’t apply to him. He would have to be tried in a federal civilian court.

Recognizing that Saipov can’t be tried at Guantanamo, Graham has argued that Saipov should still be sent there and held for a long time for interrogation about other terrorist activities. Graham criticized the Trump administration after prosecutors in New York charged Saipov in federal court with providing material support to ISIS, among other terrorism charges. He tweeted:

Appears Trump Administration continuing the Obama policy of criminalizing War on Terror by not declaring Sayfullo Saipov an enemy combatant. pic.twitter.com/Dlcs8bLIWJ

— Lindsey Graham (@LindseyGrahamSC) November 1, 2017

But the federal charges don’t necessarily prevent Trump from trying to send Saipov to Guantanamo. The George W. Bush administration attempted to declare at least two people arrested on US soil enemy combatants, and it did place them in indefinite military detention on a naval brig in South Carolina. The courts issued mixed rulings on the legality of those moves, and the Supreme Court never weighed in because the government later transferred the cases to civilian court, where they were resolved. The law is still unsettled as to whether the president has the power to declare someone an enemy combatant when he or she hasn’t been anywhere near a battlefield or US soldiers.

In 2003, the Defense Department seized a man from Peoria, Illinois, named Ali Saleh Kahlah al-Marri, who had been picked up by local authorities on credit card fraud charges a few months after the 9/11 attacks. Like Saipov, al-Marri was a legal permanent resident, but two years after his arrest on domestic criminal charges, Bush claimed he was a sleeper al-Qaeda operative and declared him an enemy combatant. The military sent al-Marri to the brig in South Carolina, where he was held without charges for eight years, before President Barack Obama ordered him transferred to a civilian criminal court. He later pleaded guilty to some of the charges.

Before Obama transferred him, though, al-Marri appealed his indefinite detention to the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals, and a three-judge panel ruled in his favor. Judge Dianne Gribbon Motz, writing for the panel, said, “[I]n the United States, the military cannot seize and imprison civilians—let alone imprison them indefinitely.” The president’s powers, she wrote, did not allow him to seize and detain al-Marri any more than “they permit the President to order the military to seize and detain, without criminal process, other terrorists within the United States, like the Unabomber or the perpetrators of the Oklahoma City bombing.”

The full 4th Circuit, then one of the most conservative courts in the country, narrowly overturned that ruling, and the case was headed to the Supreme Court. But Obama’s decision to move al-Marri to civilian court made the case moot, and the high court dismissed it. In a similar case, the Bush administration maneuvered to avoid having the Supreme Court make a definitive ruling about whether the president has the power to declare someone arrested on US soil an enemy combatant, leaving the law unsettled. A Trump move to declare Saipov an enemy combatant would resurrect these legal issues, which would take years to resolve.

There’s also some question as to whether the statute governing transfers to military detention applies to people involved with ISIS, which the government alleges Saipov was. Congress passed the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists (AUMF) in 2001 to allow the Bush administration to retaliate against those responsible for the 9/11 attacks and “any associated forces.” ISIS didn’t exist when the law was passed, and there’s no clear legal precedent as to whether the AUMF applies to ISIS. Even if it does, it’s not clear whether Saipov was actually a member of ISIS, and thus covered by the law, or simply inspired by ISIS, in which case he wouldn’t be.

“The government might prevail on these issues, but it’s an awfully big chance to take,” says University of Texas law school professor Stephen Vladeck, who adds that the question of whether the AUMF applies to ISIS is particularly thorny. That question has never been litigated, and this case might result in a court ruling that has broader policy implications for the Trump administration’s war on terror. Since 2001, the government has been using the AUMF to justify air strikes in Syria, drone strikes in Yemen, and other military actions all over the world with tentative connections to the 9/11 attacks. A court ruling against the government in Saipov’s case could severely limit the military’s ability to continue the war on terrorism abroad without further congressional action. It wouldn’t be surprising if this calculation played a role in Trump’s backpedaling on the Guantanamo transfer.

Finally, there’s the question of why Saipov would need to be sent to Guantanamo for interrogation, as Graham and McCain would like. The senators suggest that somehow the government could get more intelligence from Saipov at Gitmo, without the interference of a lawyer in federal court. But Vladeck says that’s “all a red herring” and that “there’s no reason why he can’t be interrogated even in the civilian criminal justice system.” Civilian criminal justice law allows for emergency exceptions to interrogation rules. Many terrorism cases have been successfully tried in civilian courts without such a drastic move as sending the defendant out of the country, including Boston marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and Zacarias Moussaoui, who was alleged to be one of the original 9/11 plotters.

“The only reason presumably to send someone to Guantanamo is to use coercive interrogation or torture, techniques that would not be allowed on US soil,” says Noor Zafar, a lawyer with the Center for Constitutional Rights, which has defended people at Guantanamo for 15 years. “The assumption is that if we send this guy to Guantanamo, we can torture him, because that’s where we have tortured people.”

Following 9/11 and the Iraq war, such techniques have failed to yield actionable intelligence in the fight against terrorism, and they’re one reason why so many of the Guantanamo detainees are still stuck there: Prosecutors’ cases against them have been hopelessly compromised by the government’s conduct. After Trump’s comments on Saipov, Zafar’s group noted in a press release, “Fifteen years has proven no one will ever be successfully tried or ‘brought to justice’ at Guantanamo, and the president and his supporters within his own party are deluded if they believe otherwise.”