Ray Tang/Zumapress

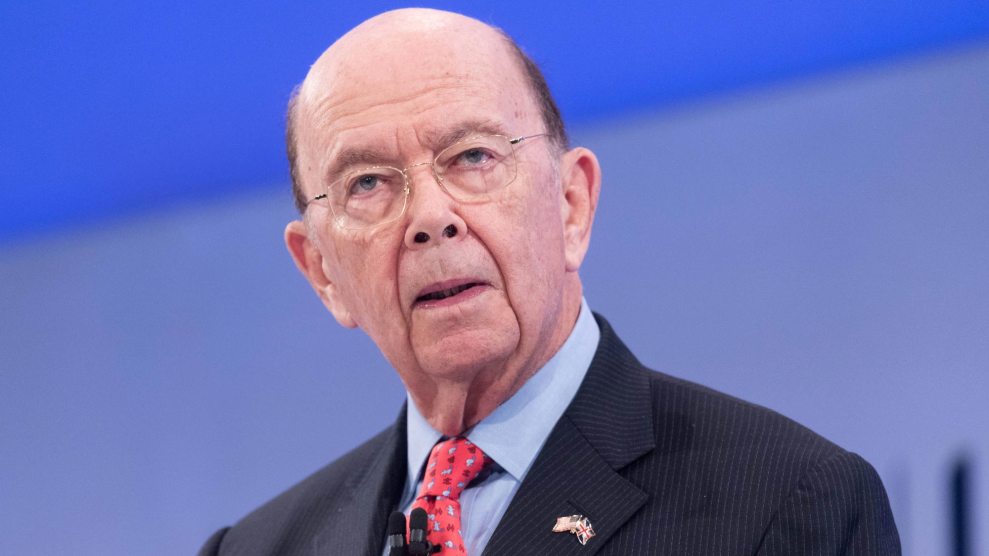

Senate Democrats recently called for an investigation into Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross’ finances, following reports that he vastly overvalued his wealth and failed to disclose his holdings in a Russian shipping company partly owned by Vladimir Putin’s son-in-law. Now the embattled mogul, whose long relationship with Donald Trump has been tested by the disclosures, is facing scrutiny by European lawmakers over allegations that he engaged in insider trading related to his 2014 sale of shares in the Bank of Ireland.

Earlier this year, Luke Ming Flanagan, an Irish politician and member of the European Parliament, the European Union’s governing body, commissioned a report on the 2008 eurozone banking crisis. The final version of this report, written by two Irish financial analysts, was presented in Brussels last week to a group of 52 European Parliament members affiliated with left-leaning parties. And it included a section covering Ross’ investment in the Bank of Ireland, in which he was a major shareholder and a member of the board of directors. The report alleges that when Ross sold off his holdings in the bank for a massive profit in 2014, he possessed inside information that the bank was relying on deceptive accounting practices to mask its losses and embellish its financial position.

Ross’ involvement with the Bank of Ireland began in July 2011, when his hedge fund, WL Ross & Co., joined several institutional investors to purchase a 34.9 percent stake in the struggling financial firm for 1.12 billion euros ($1.6 billion). At the time, the deal “led to much head-scratching,” according to the Irish Examiner. That’s because Ross and the other investors obtained stock in the company at the low price of 10 euro cents a share just months after the bank received a 3.5 billion euro bailout from the Irish Central Bank and a guarantee of up to 10 billion more. (The bank’s shares were trading at about 30 euro cents two months before the sale.) The Irish government’s decision “to sell a large chunk of Bank of Ireland at the bottom of the market” so soon after the government’s cash infusion had stabilized the institution “was on the face of it baffling,” the newspaper reported.

In 2012, Ross joined the bank’s board of directors. Two years later, he began liquidating his stake. In March 2014, he sold a chunk of his holdings at 33 euro cents a share—more than triple what he had paid for the stock. A couple of months later, he sold the remainder of his shares for about 26 euro cents per share. Together, the sales netted him a profit of about 500 million euros ($682 million). The Irish Independent reported at the time that Ross had “pulled off the deal of the century.”

The following year, offloading his Bank of Ireland shares seemed especially wise. In May 2015, the bank’s lead auditor testified before the Irish parliament that the bank had been miscalculating its losses and presenting a rosier picture of its financial health. That August, the bank’s former chief financial officer testified to this as well. He claimed that the bank had publicly disclosed its accounting practices. But the European Parliament report notes that annual reports from the bank didn’t reflect that. Due to the company’s accounting methods, the report states, “The bank would show huge artificial profits before revealing substantial losses.”

Ross sold near the top of the market. Since the 2015 admissions that the Bank of Ireland relied on flawed accounting methods, the bank’s share prices have dropped significantly. Yet as a board member, Ross would have presumably been privy to the bank’s most sensitive financial information, including its bookkeeping practices. This raises the question of what Ross knew when he sold off his shares. Was he aware that the losses the bank was deferring using flawed accounting would inevitably reappear and that he could get out of the company before the true state of its finances became clear?

Ross “had access to the loss details that Bank of Ireland kept hidden from retail shareholders,” the report states. “The profit that Mr. Ross accumulated was largely at their expense.”

Ross’ profit, Flanagan said in a statement to Mother Jones, was “money lost to the Irish people.” Flanagan also wants to know how Ross was able purchase his shares on apparently preferential terms. “Wilbur Ross and others have serious questions to answer on the purchase of Bank of Ireland shares,” he said in the statement. “How did they manage to purchase those shares for 10 cents each, when two months previously they were trading for nearly thrice that?”

The report presented to European Parliament members last week maintains that Ross may have known about the bank’s steep losses from the beginning, suggesting that the hedge fund mogul, known as the “king of bankruptcy,” possibly learned of this when he was buying into the bank and it opened up its books to him during the due diligence process. As the bank has noted, it “facilitated detailed due diligence” for Ross and his fellow investors. The European Parliament report also suggests that Ross may have leveraged information about the company’s losses from the outset to secure a good deal when he bought in.

Neither the Department of Commerce nor Invesco (the parent company of private equity firm WL Ross & Co.) responded to requests for comment. (Ross divested his shares in Invesco and stepped down as chairman of WL Ross & Co. after his confirmation as commerce secretary.)

The European Parliament report was authored by Cormac Butler and Ed Heaphy, Irish financial analysts who have been investigating the European banking crisis for the past two years. Butler, an equity and options trader and the author of two books on accounting finance, is a regular financial commentator in Irish media and has advised a number of major banks and financial firms. Heaphy is a former banker who for the last decade has provided research and expert reports on the European banking system to lawyers taking on banks or lenders.

“It’s a fairly reasonable assumption that someone with Wilbur Ross’ experience would have taken an interest in the losses that Bank of Ireland did not disclose,” Butler said. “If you know that not all the losses will be disclosed, it means that you can get out at a profit.”

If Ross was aware that the Bank of Ireland was concealing losses, he had an obligation to disclose that information before the sale of his shares, said Lawrence Harris, the chief economist of the Securities and Exchange Commission during the first term of the George W. Bush administration and now a finance professor at the University of Southern California’s Marshall business school. “Even if it’s a gray area, the very fact that there is a potential serious accounting problem generally has to be disclosed,” he added. “If he was trading on material information that should have been disclosed but wasn’t, that’s pretty close to the technical definition of insider trading.”

Eamonn Walsh, an accounting professor at University College Dublin and a principal author of a 2013 case study on Ross’ Bank of Ireland purchase, expressed skepticism about the allegations leveled in the report. He emphasized that the due diligence performed by Ross is standard practice: “Somebody who is investing a billion on behalf of other people, there is an expectation that they would do due diligence.” Had they discovered accounting problems, Walsh said, Ross likely would have walked away from the investment.

Stella Fearnley, a former financial auditor and now a professor of accounting at England’s Bournemouth University, called the report’s allegations “very credible.” She added, of the hedge funds that invested in the Bank of Ireland: “If they were allowed to look at the books, very probably they could see opportunity as a result of the accounting model.”

The European Parliament report cites past allegations of insider trading involving Ross, pointing to a 2016 lawsuit accusing the hedge fund mogul of making suspiciously timed trades when he was on the board of mortgage giant Ocwen Financial. (The case was settled with no admission of guilt by Ross.) While Ross was on Ocwen’s board, according to a SEC order, Ocwen masked losses using an accounting method that enabled the company to overvalue certain financial products.

Ross’ Bank of Ireland windfall has also caught the attention of two members of the Dáil, the lower house of Ireland’s parliament, and they have called for an investigation of the bank, including Ross’ dealings with the firm.

“When Wilbur Ross…purchased Bank of Ireland shares in 2011 and then flipped them in 2014 for a profit…he did so with the advantage of having access to the financial position of the bank, which was not in the public domain,” said Mick Wallace, a Dáil member from Ireland’s Independent Party, during a floor debate in February. (Wallace has faced several financial misconduct claims of his own in Ireland. In 2011, his construction company was court-ordered to repay $19 million in loans to an Irish bank, and in 2012, he agreed to a seven-figure settlement with the country’s tax agency for underpaying taxes.)

During that same session, Catherine Murphy of the Social Democrats said, “Ross went on to make hundreds of millions from that transaction.” She added, “Bank of Ireland still exists but the dubious accountancy practices fed vultures and profiteers…The establishment of a commission of investigation is fully warranted.”

A Bank of Ireland spokesman declined to address specific questions about the European Parliament report’s allegations, including whether the bank had fully disclosed its accounting methods. He told Mother Jones in a statement: “At all times, as a regulated and publicly quoted company, Bank of Ireland complies with all of the rules, regulations and standards which govern such entities and transactions.” And he noted that in June 2011 “a detailed circular was posted to existing shareholders and a detailed prospectus was published and made publically available on the Bank’s website to enable all shareholders to understand and assess the Bank’s trading and financial position, relevant risk factors and future prospects.”

This week, Flanagan and Butler will present the European Parliament report to lawmakers and members of the media in Dublin in the hopes of pushing for financial reforms that will prohibit the kind of deceptive accounting employed by Bank of Ireland, which they said allowed Wilbur Ross to make hundreds of millions of dollars at the expense of ordinary shareholders. “Every investor needed to know the true financial position of the Bank of Ireland,” Butler said. “Every investor did not know, but Wilbur Ross did know, and that put Ross at a huge advantage.”

Update: Mother Jones repeatedly requested comment from the Commerce Department before publication of this article, sending Ross’ spokesperson a copy of the report prepared for the European Parliament. After publication, department press secretary James Rockas sent this statement:

The Mother Jones article about Bank of Ireland is a factually incorrect effort to smear me. The report they reference was commissioned by a single member of the European United Left-Nordic Green Left, whose original member parties included the French, Italian, Portuguese and Greek communist parties. Here are the facts:The shares purchased by WL Ross Funds, and also by Fidelity Funds, Capital Research, Fairfax, and Kennedy Wilson, were the unsubscribed portion of a rights offering made available to the Irish Government and public shareholders on the preferential terms.We bought them at the same price they were offered to those other public shareholders. The government at the time had designated a majority of the Board of Directors and was the largest shareholder. The investment bankers appointed by the government were world class firms and it was their obligation to assure proper dissemination of all material information.The report’s author implausibly says that I learned of what he calls improper accounting during the due diligence and used that information to get a cheap price. This is an obvious non-sequitur, given the process described above.The Bank’s basic accounting used IAS39, as required by the regulators, and was reviewed by PwC, the Bank’s outside auditors. The Bank’s financial statements were reviewed in excruciating detail by the Irish regulators, the ECB, the SSM, and the IMF.The Bank also issued a variety of securities at different points during WL Ross Funds’ ownership. Due diligence was performed in each case by the investment bankers and the purchasing institutions. They clearly found nothing wrong.When we sold the last block of WL Ross Funds’ holdings, other investors such as Fairfax, which had representation on the Board, decided not to join in the sale. The stock subsequently traded at a much higher price.The report incorrectly says that there were official confessions of improper accounting in May 2015 after the final sale. In fact, the Bank reported earnings for 2015 of 947 million euros, 161 million euros more than in 2014, when WL Ross Funds sold the shares. Earnings in 2016 also were higher than in 2014.If there actually had been a confession of accounting wrongdoing in 2015, it would have had to be reflected in the financials.The report also brings in the Ocwen litigation, an irrelevance at best. That case was settled at no cost to me and I never even was called to appear in court. It clearly was mentioned as a smear to imply that I had done something wrong—this is simply not the case.