Edel Rodriguez

Last winter, about 10 months before Donald Trump managed to revive Colin Kaepernick’s protest movement and set off a fresh national debate on race, patriotism, and the emotional stability of the president of the United States, Ben Hunter was asked to perform “The Star-Spangled Banner” for a crowd of about 600 people. The occasion was the annual conference of Citizen University, a nonprofit run by former Clinton White House adviser Eric Liu. Presenters at the meeting included progressive authors and activists, broadcasters and businesspeople. Slow-food guru Alice Waters was on the bill, as was Greenpeace top dog Annie Leonard. Hunter was the event’s musician-in-residence. But the anthem request gave him pause.

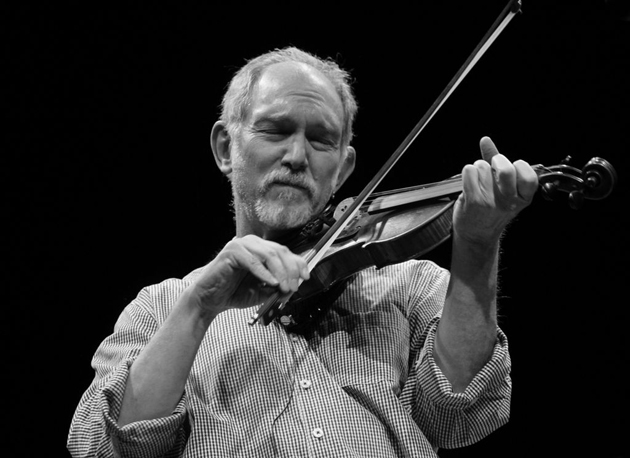

Hunter, 32, is biracial and identifies as black. He took up classical violin at age five and now, as part of a Seattle-based duo with banjo player Joe Seamons, makes his living researching and performing old-time American music. So he already knew a bit about the anthem’s dark past.

At first he said he’d do it if he could perform the whole song—including the verse in which slave owner Francis Scott Key, an outspoken white supremacist, rails against “the hireling and the slave.” And then, after doing more research, Hunter recalls, “I just wasn’t into it at all.”

In the end, he agreed to perform an instrumental version, “but I’m going to talk about it first,” he told the organizers. So, before picking up his fiddle, Hunter spent five-plus minutes on stage educating the crowd on the anthem’s history. “The fact that the melody is actually an old British fraternity song,” Hunter told me. “I mean, right there that tells you how ass-backward our thoughts are on what this anthem means. And then I kind of played it in a minor key. I played it much more rubato and recitative—”I didn’t hold the melody exactly, and I made it more bluesy.”

The intent, Hunter says, was not “for everybody to stand up and put their hand over their heart. I performed the national anthem for everybody to actually reconsider if this song represented what it was to be American. (“What he did,” Liu says, “was very moving.”)

Hunter’s performance is featured in Mother Jones‘ July 4 podcast.

I hadn’t actually called Hunter to talk about the national anthem, but rather to discuss something I’d observed as a fellow old-time musician: Our musical heritage is a racial minefield. Prejudice pops up regularly to complicate tunes we’d rather simply enjoy—in the same way it feels weird these days to listen to a Bill Cosby record or rent a Mel Gibson movie.

Take “Big Bend Gal,” a catchy fiddle-and-vocal number I learned from my Vermont cousins a few summers back: “There’s no use talking about the Big Bend Gal who lives at the county line/For Betsy Jane from the prairie plain just leaves them way behind.” The song is about a fieldhand everyone is smitten with: “She’s the queen of the whole plantation!”

Here’s me and some friends playing it on a San Francisco radio show…

Back home in California, I looked up the song’s history. It turns out “Big Bend Gal” was first recorded in 1927 by the Shelor Family of Virginia. The Shelors, who were white, sang it in a raw hillbilly style with lyrics that put a damper on the festivities. Whereas my cousins sang, “A fellow’ll turn around and come pretty quick when he hears that pretty gal laugh,” the Shelors crooned, “The n—s turn around…” And my cousins’ line about “the fellers in the cotton patch” was originally…well, you get the picture.

As a white musician who cares about racial justice, what do I do with that knowledge? Do I sing the sanitized version, or skip the words, or leave the whole thing in a box? Should I feel conflicted, even, about playing a haunting instrumental like “Mace Bell’s Civil War March” knowing it came from a Texas fiddler who served in the Confederate Army? (And does it matter whether the marchers were advancing or retreating?)

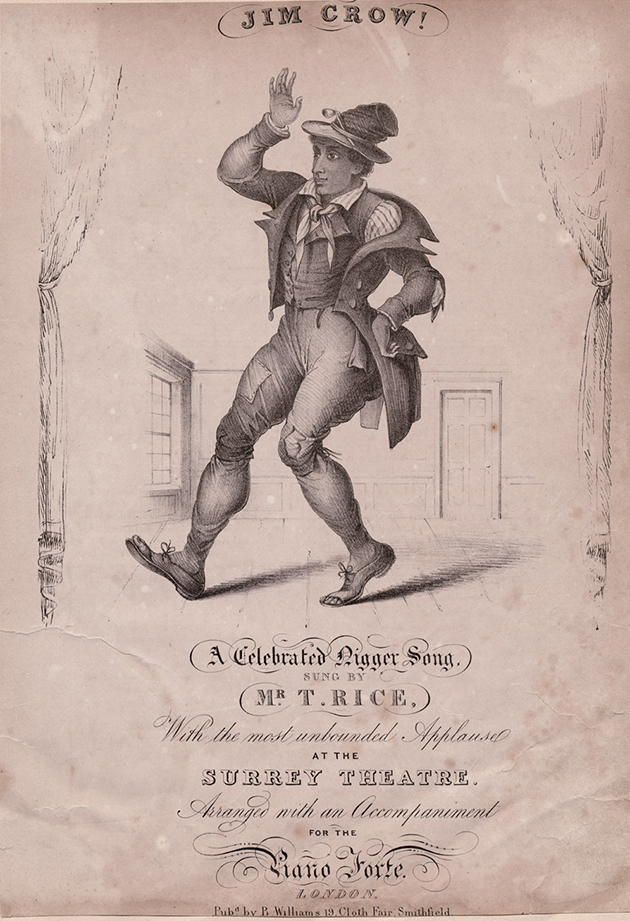

At a fiddle workshop another time, I learned an instrumental version of a tune called “Jump Jim Crow.” Googling it turned up lots of unverifiable stuff about the song’s provenance, so I tracked down historian WT “Rip” Lhamon Jr., an authority on early American pop culture. The Jim Crow persona, Lhamon told me, was a recurring presence in old slave songs, including “Jump Jim Crow”—whose refrain goes: “Weel about and turn about and do jis so/Eb’ry time I weel about I jump Jim Crow.”

In the early 1830s, a white actor named Thomas Dartmouth Rice adopted the song and its eponymous trickster character for a comedy act that would catapult him to international fame. Donning rags and blackface, Rice performed send-ups of black speech and culture, song and dance. He wrote endless new verses for his signature ditty—corny slapstick humor with the occasional social commentary:

And if de blacks should get free,

I guess dey’ll fee some bigger,

An I shall concider it,

A bold stroke for de niggar.

Sheet-music cover, circa 1836.

Rice’s success paved the way for a wave of more mean-spirited blackface performers, and before too long the Jim Crow name was synonymous with America’s apartheid. In the post-bellum period, black entertainers also did blackface routines for a time, before moving on to blues- or jazz-based vaudeville acts. “The first one or two generations of black performers took those stereotypes to a far deeper degree of racist imagery than even the white performers did,” says Dom Flemons, a founding member of the Carolina Chocolate Drops who in 2014 moved on to a solo career. (His latest passion is black cowboy songs.)

Blackface was “the only game in town” at the time, North Carolina historian David Gilbert, who also wrote a book on the subject, told me in an email. Black entertainers “acted, sang, and performed in the few caricatures available to them: the dandified, urban Zip Coon and the slow-witted Sambo, to name the two most prominent types. Often these ‘coon’ caricatures traded in razor violence, lust, and gastronomical stereotypes like chicken and watermelon. But these were the stereotypes of their day, not just in minstrelsy but in the advertising and consumer culture.” Black performers often “subverted these images,” Gilbert added, “and black audiences could tell.” But the white minstrelsy had evolved into, as Flemons puts it, something “more sinister.”

Lots of old songs have complicated histories. Among the most famous is “Dixie’s Land,” a tune usually credited to Ohio-based showman Daniel Emmett, who founded one of the first traveling blackface troupes during the 1840s. “Dixie” later became an unofficial Confederate anthem, with words that seemed to express nostalgia for a lifestyle based on the brutal oppression of black people: “Oh I wish I were in the land of cotton/Old times there are not forgotten.” The song isn’t racist per se, Flemons told me, “but how it’s applied in the world—that’s a whole different thing.” This fraught past is why, in 2016, the University of Mississippi said its marching band would no longer play the song at sporting events—”Dixie” was too troubling even for a school that called itself Ole Miss.

But there’s another side to the story. In their 1993 book, Way Up North in Dixie, husband-and-wife researchers Howard and Judith Rose Sacks chronicled extensive cross-pollination between black and white musicians in central Ohio during Emmett’s day. “Documents including Emmett’s jig notebook indicate that Emmett collected material during his homeplace visits from local musicians, including Thomas Snowden,” the couple told me in an email. (Emmett’s notebook included a tune labeled “Genuine Negro Jig,” which became the title of the Chocolate Drops’ Grammy-winning 2010 album—the song appears on the album as “Snowden’s Jig.”)

Thomas Snowden was the patriarch of a family of black string-band musicians sought out regularly by whites for performances, songs, and instruction. And while there’s no proof that the Snowdens composed the tune, the Sackses said, “it is such a powerfully held piece of community identity that the local black American Legion erected a tombstone in the Snowden family graveyard” that reads: “They taught ‘Dixie’ to Dan Emmett.” (“Dixie” is also the subject of a documentary film and an episode of the new history podcast, Uncivil.)

In Emmett’s time, “if you were a white person and you went into a black neighborhood and learned a tune from a black person, it wasn’t cool to advocate that you learned it from a black person,” says 63-year-old Earl White, a black fiddler and early member of the Green Grass Cloggers, a traditional North Carolina dance group. “Blacks made a very large contribution to old-time and country music, but kids today, they have no idea.”

“A lot of the old-time tunes that we play today, most people only know of the Caucasian reference,” he adds. “There are tunes I’ve been playing for years and only recently found out that they were created by a black person, and learned from a black person.”

In any case, White says, there’s no song he’ll refuse to play. “If it’s a good tune, I’ll play the tune,” he says. “I could pretty much care less who wrote the tune or even what the perception of the tune was. If this was a sign of their times, then I appreciate it from the musical aspect.”

He recalls one dicey example he sang for a college musicology class taught by the jazz saxophonist Archie Shepp. “A lot of the younger black guys were highly offended by me using the N-word and various other aspects of the song,” White says. “All I was trying to do was share the information in its original form.”

“People are trying to find modern sensibilities in stuff that was not built on modern sensibilities,” Flemons told me. In 2015, he performed an instrumental version of Stephen Foster’s “Ring, Ring de Banjo” at a Foster-themed event with the Cincinnati orchestra. Foster’s racist lyrics are “absolutely unacceptable” nowadays, and “I would never think to perform that song outside the context of that specific show,” Flemons says. But these once-popular songs “are a document of what happened,” and failing to acknowledge that history would “completely devalue the strength of how far we’ve come.”

In short, to bury the hurtful pop culture of our past is to hide from the reality that the horrors of slavery and its aftermath are, to quote the sideview mirror, closer than they appear. Prejudice “is still in our blood, it’s still in our actions, it’s still in our Constitution—little fragments that are left over and covered up by new laws,” Ben Hunter says. “In the right context, it’s important to perform “Run, Nigger, Run'”—another slave song adopted by white performers—”because black and white people were singing that song, probably for different reasons.”

“I’m not the first to say this, but it’s important for white people to be uncomfortable,” Hunter continues. “One of the beautiful things about American folk music is that it very vividly and honestly faces those truths.”

I suppose my best option, then, is to embrace the discomfort and continue playing tunes like “Big Bend Gal,” “Jump Jim Crow” (the instrumental), and “Mace Bell’s Civil War March,” and share what I’ve learned with others. I’ll leave “Run, N—-, Run” to the black performers. “Dixie” I’ve disliked ever since I was forced to sing it in the fifth grade. As for the anthem, if the Kaepernick-bashers would just read up a little, they might get why so many black Americans—and many other Americans, too—feel conflicted about this official expression of our national pride. Sometimes history isn’t so complicated.

_____

Click here to check out “20 Favorite Tunes From Old-Time Black Musicians,” as curated by Dom Flemons, Earl White, and Joe Seamons.