Innocenti/Cultura/ZUMA

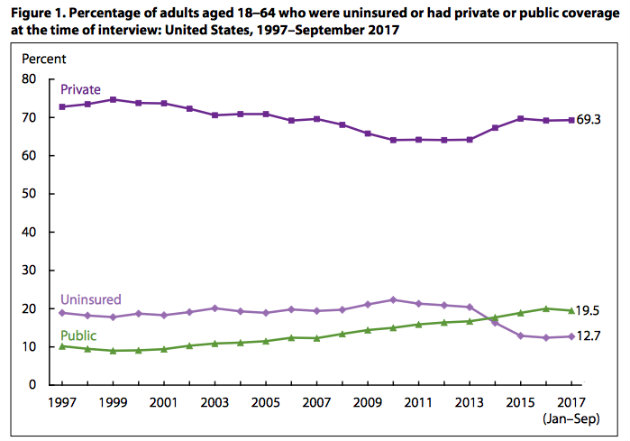

For all of last year’s talk about drastically reworking our health insurance system, and despite all the failed Republican attempts to “repeal and replace” the Affordable Care Act, new evidence suggests that little has changed in terms of how many Americans are insured. A new report out today from the National Center for Health Statistics found no significant change in the insured rate for the first nine months of 2017 compared with the previous year.

According to the report, 28.9 million Americans—about 13 percent of adults and about 5 percent of children—were uninsured, compared with 28.6 million in 2016.

“In light of the debate that has been going on in the past year, this is good news,” says Rachel Garfield, associate director of Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured. “There has been a lot of uncertainty about what would happen with the ACA and I think some confusion among the public.”

“It’s encouraging,” adds Stacey McMorrow, a health economist and senior research associate at the Urban Institute, “to see that there were not any substantial declines in coverage in this period, with all of the rhetoric around repealing and replacing the ACA.”

In 2010, the year Obamacare went into effect, 48.6 million Americans, or about 16 percent of the population, lacked health coverage. The latest data shows how, over seven years, the ACA has achieved its goal of reducing that number.

But experts worry that the GOP’s December repeal of the individual mandate, the part of the health care law that requires all Americans to have insurance or pay a fine, could reverse that course. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office has estimated that without the mandate, 13 million fewer people will have insurance in the coming decade. (The CBO’s mandate estimates are controversial with some Republicans.)

In a Kaiser Family Foundation poll this past October, the vast majority of respondents said they would buy health coverage even without the mandate. So it’s unclear what the scope of that loss of coverage will be, Kaiser’s Garfield told me. “By and large people want coverage when it’s available to them,” she says. “It is possible that particularly people who are in the lower end of the income spectrum may make the decision it’s not something they can afford anymore.”

The Urban Institute’s McMorrow notes that the new report points to what she calls “warning signs.” For one, states that decided not to expand Medicaid under the ACA have seen a slight uptick in uninsured rates for adults and children—the increase is not significant, but it could indicate a reversal after years of decline. Another warning sign is the small decrease in coverage among Hispanics—this could signal a change in consumer behavior, especially if the debate around immigration ends up affecting insurance enrollment.

What’s more, the latest data didn’t include the final quarter of 2017, a time period that encompassed the start of the ACA’s open enrollment period and was capped by passage of the Republican tax bill, which repealed the individual mandate. Next year’s data, in other words, could prove a good deal more interesting.