Bishop Julian Smith (left) and Rev. Ralph Abernathy (right) flank Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., during a civil rights march in Memphis on March 28, 1968.Jack Thornell/AP

February 1, 1968, was a dreary day in Memphis, Tennessee. As a storm rolled over the city, blanketing the streets in torrents of rain, Robert Walker and Echol Cole grew desperate for shelter. On the job collecting trash, they holed up in the back of their garbage truck, the one place city rules allowed them to seek cover. Tucked away in the rig’s hydraulic compactor, the two men became trapped in a malfunctioning grinder and were crushed to death by the very machine they had turned to for shelter. Describing one of the men’s attempt to escape, an onlooker recalled, “Suddenly it looked like the big thing just swallowed him.”

In popular retellings, Walker and Cole’s grisly deaths ignited Memphis sanitation workers’ historic campaign for dignity and higher pay. Their efforts would attract the attention of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who would spend his final days in the city. The truth is that Memphis’ sanitation workers had been organizing for years and had been met with a wall of resistance raised by powerful adversaries among the city’s white leadership. According to historian Jason Sokol, the deaths of Walker and Cole were but the most powerful spark behind the activism that swept Memphis in 1968.

As the 50th anniversary of King’s assassination approaches, the conflict that drew him to Memphis remains unresolved. “For a lot of these people, it is still 1968,” says Maurice Spivey, chair of Memphis’ chapter of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), the union that represents the city’s sanitation workers. “I know these folks saying, ‘A whole lot has changed.’ But a whole lot has stayed the same.”

A man marches alongside a tank during the sanitation strike in Memphis on March 29, 1968.

Barney Sellers/ ZUMA

King’s decision to travel to Memphis was rooted in his increasingly vocal effort to combat not just racial inequality, but economic exploitation. At the time, King and other civil rights leaders had been in the middle of planning a second march on Washington that would demand an end to racism and poverty. Looking beyond the nation’s black slums to Appalachia and rural Mississippi, they had announced the Poor People’s Campaign in December 1967. King, who had sanded down the more radical edges of his progressive economic vision in the past, now openly imagined a “nonviolent army of the poor” setting out to vanquish squalor through a “radical redistribution of economic and political power.”

King had been building toward this sort of confrontation for years. That’s at odds with the widely held belief that he only sharpened his critique of American capitalism in the final years of his life. But as Thomas F. Jackson persuasively argues in From Civil Rights to Human Rights: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Struggle for Economic Justice, King’s “pilgrimage to Christian socialism” was well underway by the early 1950s. King wrote of realizing as a teenager that the “inseparable twin of racial injustice was economic injustice.” And at age 21, he pointed to his memories of Depression-era bread lines as the source of his “anti-capitalistic feelings.”

“Dr. King understood the importance of that strike,” says Lee Saunders, president of AFSCME, which came to represent the striking sanitation workers during the strike. “He understood the connection between economic rights and civil rights and he gave his life in support of that strike.”

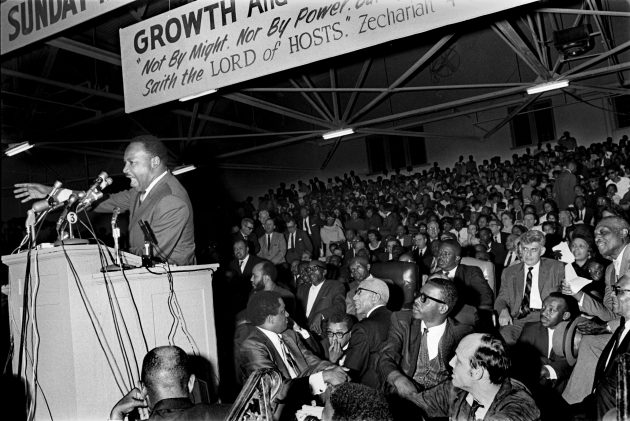

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speaks at the Mason Temple in Memphis on March 18, 1968.

Vernon Matthews/ZUMA

Speaking to a crowd of 15,000 at Bishop Charles Mason Temple on March 18, 1968, King thundered, “You are reminding, not only Memphis, but you are reminding the nation that it is a crime for people to live in this rich nation and receive starvation wages.” King, who was largely freestyling that night, as he often did, went on to speak plainly in support of the sanitation workers’ strike. ”Along with wages and other securities, you’re struggling for the right to organize,” he said. “This is the way to gain power…Don’t go back to work until all your demands are met.”

In the weeks that followed, the strikers’ resolve stiffened in the face of reprisals and tragedy. A peaceful demonstration on March 28 was met with violence from white Memphians on one side and armed police officers on the other, one of whom shot dead a 16-year-old protester. Seven days later, on an evening when King seemed to wear his burdens more lightly than usual, the 39-year-old reverend was gunned down by a white supremacist on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel.

As the future of the civil rights movement, and what historian C. Vann Woodward has called “America’s Second Reconstruction,” was thrown into chaos, Memphis’ black sanitation workers pressed on. On April 16, after months of stonewalling by the city’s white decision makers, the workers secured a contract that brought better wages along with recognition of their union, bringing the two-month strike to a close.

Five decades later, Spivey charges, the victories of 1968 have been whittled away to the point “where rich powerful men in general, but specifically white men, don’t have any problem basically ignoring the vast majority of the needs of their employees and workers.” The city’s sanitation workers sit on on top of 200-degree truck engines in summer temperatures that can reach 105 degrees. They “still work on garbage trucks that don’t have AC,” Spivey laments. “Where are you going go to get some relief? This is what we still dealing with, man.”

Spivey tells the story of 36-year-old Darryl Seay, a sanitation worker who suffered a massive heart attack on the job on an extremely hot day in July 2017. “He was basically worked to death,” says Spivey, dying “on the dirty, nasty, filthy ground right beside his garbage truck.” As a temporary employee, Seay “had no right to be in a bargaining unit, no paid benefits, no paid vacations, he had no voice.” Spivey cuts a clear path back to 1968: Echol Cole and Robert Walker “had no rights to be in a bargaining unit, no paid benefits, and no paid vacations” at the time when they were crushed to death. “Tell me what has changed in 50 years?” (In February, Mayor Jim Strickland issued a statement defending the city’s record, noting that “there has been tremendous progress” for the city’s sanitation workers: “Our current workers make a living wage, receive benefits and have a strong retirement plan—all items that weren’t provided in 1968.”)

Collecting garbage is one of the country’s dirtiest and most dangerous jobs. Earlier this year, ProPublica found that an average of one worker in the waste and recycling business dies on the job every week, making it “the fifth most fatal job in America—far more deadly than serving as a police officer or a firefighter.” Workers have lost limbs, been crushed to death, and “marked from head to toe” with scars. Those who had complained about the safety hazards said hours suddenly dried up.

A memorial march for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in downtown Memphis on April 8, 1968.

The Commercial Appeal/ZUMA

Union leaders are emphatic that the strike’s anniversary should entail something more than an empty celebration of a historic moment. “We’ve got to commemorate what went on in ’68,” Saunders says, “but we can’t forget that those workers died for a reason, those sanitation workers went on strike for a reason.” AFSCME is trying to expand its membership ahead of what could be a devastating Supreme Court ruling on public sector unions, and is teaming up with the Church of God in Christ to train organizers “to go back into the communities and talk about the economic and racial issues” that affect poor people and people of color. It’s dubbed the nationwide effort “I AM 2018,” echoing the iconic “I AM A MAN” slogan of 1968.

To the legions of curious reporters and history nerds now digging into the city’s past, Spivey asks that they “not forget about us next year. Nobody was here last year when we were getting beat up by management, when they were trying to privatize us. We are trying to tell the story that we’ve been telling forever. This is the only job in the world that has Dr. King’s blood on it.”