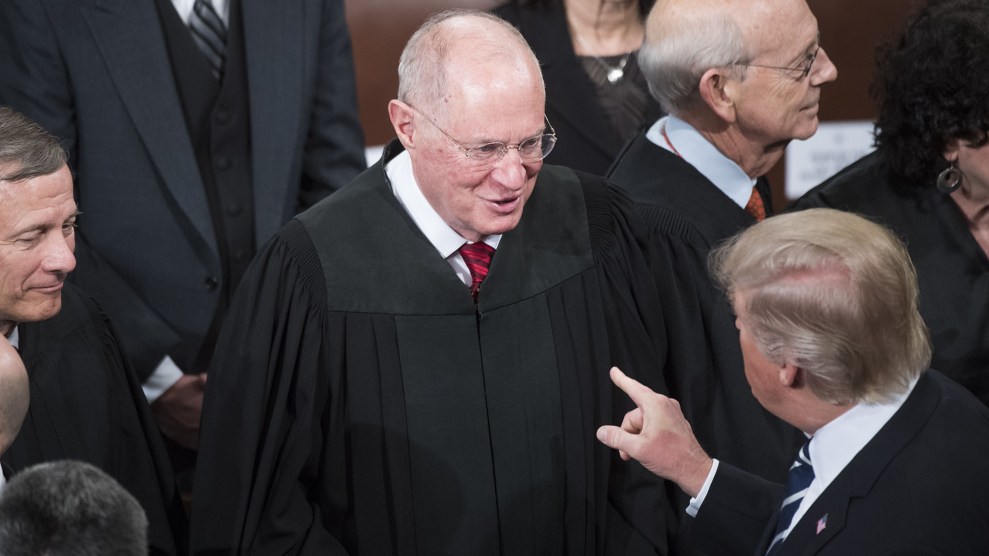

President Donald Trump greets Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy after addressing a joint session of Congress in February 2017. Tom Williams/Congressional Quarterly/Newscom via ZUMA

The retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy could signal a dramatic turnaround in protections for minority groups. More than any Supreme Court retirement in decades, Kennedy’s exit could strike a mortal blow to abortion rights and other protections for groups that have been subject to discrimination.

For more than 40 years, abortion has been a constitutional right for women in the United States. That right has been repeatedly upheld because Kennedy, a Republican appointee, was uncomfortable with undoing the Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade—though he did limit it multiple times. But President Donald Trump will almost certainly nominate a justice hostile to abortion rights. While the court is unlikely to ban abortion outright, it could overturn Roe and send the matter back to the states to resolve. Some states would impose stringent new limits on abortion or ban it completely.

Some Republican-controlled states have already prepared to ban abortion if Roe is repealed. As of today, 18 states will automatically ban abortion as soon as Roe is overturned thanks to so-called “trigger laws.” With that possibility now on the horizon, more states could pass those laws.

A year and a half ago, I wrote about the 18 states that have “trigger” laws on the books to ban abortion the minute the Supreme Court gives them the go-ahead. Justice Kennedy’s retirement makes that possibility more real than ever: https://t.co/wwG0fUWLmF https://t.co/g3qbBlH5KJ

— Hannah Levintova (@H_Lev) June 27, 2018

Though Kennedy was a conservative justice, he gained a reputation as a moderate due largely to his support for gay rights, including marriage equality. But the struggle for equal rights under the law for LGBT individuals is far from over. One of many undecided issues on this front is whether merchants or businesses can deny services to people because they disapprove of their LGBT identity. One such case, Arlene’s Flowers v. Washington, could end up before the court in the next year. In this case, a florist refused to sell flowers to a same-sex couple for their wedding. The conservative majority on the court has shown it is extremely attentive to the religious rights of people who disapprove of homosexuality, but it has displayed few qualms about creating a two-tiered commerce system in which LGBT people have access only to some businesses—a reality African Americans faced before the civil rights movement.

In some parts of the country, it is still legal to fire people because of their sexual orientation. Lower courts have recently begun to grapple with this issue. In two recent cases, federal appeals courts have decided that anti-LGBT discrimination is illegal gender discrimination, adding an extra level of protection for people discriminated against because they are gay or lesbian. But without Kennedy on the court, that trend may soon be reversed.

Then there’s housing discrimination. The last major piece of civil rights law from the 1960s was the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Now its ability to combat segregation is uncertain. Passed in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, the law was intended to end pervasive segregation in housing across the country. In 2015, Kennedy’s vote preserved a key element of that law. In a 5-4 decision, he joined the court’s liberal wing to uphold so-called “disparate impact” liability, maintaining the law’s authority to root out policies that have a discriminatory effect on minorities. Without Kennedy, a more conservative court will likely welcome the next opportunity to limit protections from housing discrimination.

Affirmative action is another area where Kennedy has prevented the court from moving further to the right, protecting college admissions policies in some cases to help diversify student bodies. In recent years, Kennedy twice worked to preserve the University of Texas’ admissions criteria, which include race as one factor for admission. In 2016, Kennedy joined the court’s liberals in a 5-4 opinion upholding the university’s policy. But the other conservatives were ready to throw out affirmative action policies for people of color, and they may soon get a chance to do so, as a case from Harvard University is already making its way toward the Supreme Court.

Kennedy also provided a key vote on decisions that protect inmates on death row. Though he was by no means a liberal on criminal justice issues, he did vote to place limits on capital punishment, opposing executions for juvenile offenders, the intellectually disabled, and people guilty of crimes other than murder. The United States is the only Western democracy that uses the death penalty. Without Kennedy, executions could become even more gruesome and widespread.

By no definition is Kennedy a liberal. He voted to strike down the Affordable Care Act and authored Citizens United, the 2010 decision that ushered in an era of enormous outside spending on elections. He joined the conservative justices in gutting voting rights in 2013, when the court knocked out a key provision of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Just this year, he joined the conservative majority in two major voting rights rulings that will increase voter purges—particularly of poor and minority voters—and increase racial gerrymandering that dilutes the influence of people of color. Still, when it comes to abortion and racial discrimination, for years Kennedy provided intermittent relief from the aggressive vision of the court’s conservative justices. Without Kennedy, nothing is off the table now.