Immigration attorney Ruby L. Powers standing at the entrance to the Port Isabel detention center where hundreds of separated parents are being held.Mark Helenowski/Mother Jones

Ruby L. Powers’ most recent journey to the Port Isabel detention center in Los Fresnos, Texas, began with an early-morning flight from Houston that brought her to south Texas just after 9 a.m. After a circuitous drive around Gulf Coast roads that had recently been flooded by heavy rain, she reached the gate of the detention facility about three hours later, popped the trunk for security, and headed in. Over the next seven-and-a-half hours, in a series of rapid-fire and often emotionally wrenching meetings, Powers met with 11 different parents who had been separated from their children. Only one of them had already individually spoken with an attorney.

The Department of Homeland Security has named Port Isabel the “primary family reunification and removal center for adults” in its custody. In practice, that means Port Isabel houses hundreds of parents whose children were taken by the Trump administration. After roughly three weeks apart, their separation may be ending now that a federal judge has ordered DHS to reunite separated families within 30 days—and within 14 days for children who are younger than five. But that doesn’t mean they will be released from detention anytime soon, only that the Trump administration has decided to replace forced separation with indefinite family detention as part of an ongoing court battle over a 2016 court decision that requires children to be released from family detention within about 20 days.

Regardless of when, or even if, they are reunited, the parents with whom Powers will meet, their children, and thousands of others will still need to convince immigration officials that they have a right to asylum or other legal protections that will allow them to remain in the United States. For the last month, a small army of pro bono lawyers has been traveling in and out of Port Isabel to help them build their cases—a group of about 10 lawyers had been there a week before Powers arrived, and their reinforcements were arriving later that night. But last Tuesday, Powers was alone.

Jodi Goodwin, a local immigration lawyer who is helping organize the effort, says lawyers have met with about 210 of the approximately 350 separated parents at Port Isabel. The numbers are unclear, Goodwin adds, because “ICE won’t tell us, and they’re certainly not giving us a list.” The South Texas Pro Bono Asylum Representation Project, the organization Goodwin is working with, receives many of its referrals through word of mouth as separated parents tell lawyers about additional parents in their dorms who need help. “They were still giving us names yesterday,” Goodwin said on Sunday.

The seven men and four women with whom Powers met were from the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras and had been separated from their children for about two weeks. Powers believes they were all prosecuted under the Justice Department’s zero-tolerance initiative. Some still had not had any contact with their kids, while others had managed one or two calls ranging from about two to 10 minutes. The calls were sometimes so brief that parents didn’t find out where their children were located. Add to these concerns their struggles to find some way to manage their own situations. One woman fled to the United States after a judge held her responsible for the domestic abuse inflicted by her husband. In another case, a man’s in-laws blamed him for not having been able to afford his late wife’s medical treatment and threatened his life when his wife died a few months after giving birth.

Powers is exactly the kind of lawyer a migrant might hope to work with. Her mother grew up in a missionary family in Saltillo, the capital of the border state of Coahuila, and always told Powers that she learned English by watching Captain Kangaroo. But Powers had to learn Spanish on her own, because her mom didn’t feel comfortable speaking Spanish during Powers’ childhood in rural Missouri. Now married to a Turkish immigrant, Powers has about a decade of experience with asylum claims and runs a Houston immigration law firm that employs four other attorneys.

She is warm and attentive, bringing to her clients the invaluable mix of lawyering and social work that asylum cases often require—and a deep commitment to providing migrants fleeing persecution with strong legal representation. Like other immigration lawyers, she is spending thousands of dollars’ worth of time working pro bono, not to mention the days she is apart from her family. During her marathon of cases on Tuesday, she considered water and coffee nuisances that forced bathroom breaks. Nonetheless, this first visit did not guarantee that she would be the attorney following these clients’ cases; some of them may never be adequately represented. This is a fact of life for those with little or no money, who now find themselves forced to navigate a rapidly changing immigration justice system while detained in remote corners of the United States.

The Port Isabel detention center is only about 20 miles north of the US-Mexico border, but the landscape of the surrounding area feels much closer to coastal Florida than a Texas border town. It’s swampy and dotted with palm trees, and a straight line east would run through the Everglades. The beach community on nearby South Padre Island features bait-and-tackle shops, mid-rise residential towers, and the usual deals for snowbirds known locally as Winter Texans.

Hidden away at the edge of Los Fresnos, a town of about 6,600, is the Port Isabel Service Processing Center. The road leading there from the south is currently closed for construction, though most people seem to ignore the signs and use it anyway. Eventually, the seal of the Department of Homeland Security appears alongside an open gate that leads onto a straight, desolate road.

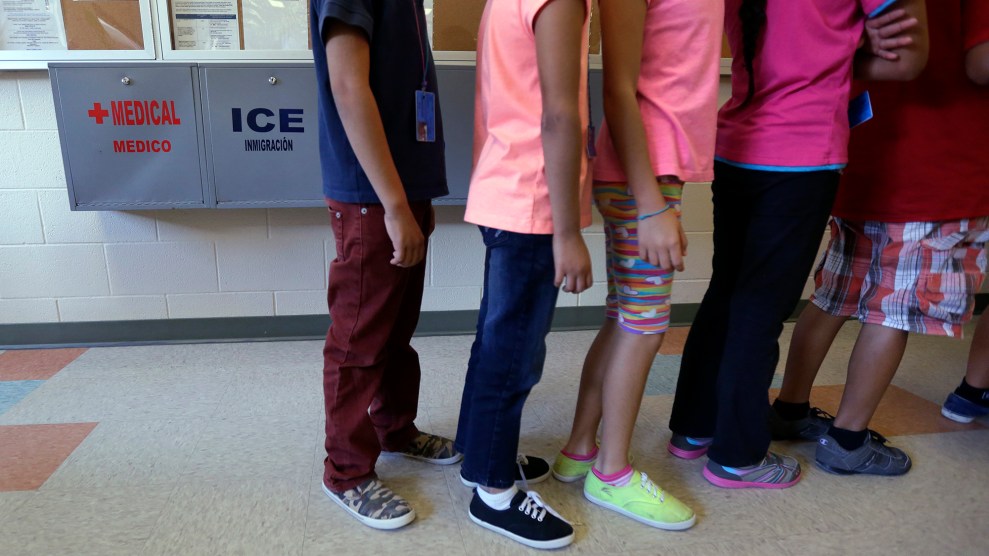

Mark Helenowski / Mother Jones

When she was leaving the detention center at 7:30 p.m. after her marathon day of meetings, Powers texted me two words: “Very intense.” Later, we met at a Gabriella’s Italian restaurant on South Padre Island, a bustling red-sauce joint with the usual calamari and eggplant parmesan, as well as pizzas such as the “Leaning Tower of Cheeza.” Feeling much closer to my native New Jersey than to a Texas detention center holding hundreds of separated parents, I listened as Powers recounted the challenges immigration lawyers faced in their efforts to provide effective counsel at Port Isabel.

First, there are the ever-changing and seemingly arbitrary requirements attorneys must comply with before they first meet with clients. Powers initially filled out paperwork in blue ink, for instance, before learning that black ink was required. She already knew to bring a quarter for the lockers in which she had to store jewelry and other personal effects not allowed in the visitation room. Because watches have been banned more recently, she sometimes asked a guard for the time, then resorted to gauging how long her meetings were by checking the shadows outside. As she sat in a roughly five-by-five visitation room, separated parents appeared before her in dark blue uniforms. Their only accessory was a bracelet listing their name, date of birth, and the “alien number” ICE uses to track them.

The logistics are negligible in comparison to the emotional and intellectual demands each meeting requires. From the moment she begins to talk with the parents, “you’re sort of juggling the two minds,” she says. She processes the traumas her clients recount as a human being hearing a “horrific story,” but also with the detachment of a lawyer trying to assemble the pieces and figure out how they fit into “the blocks” of asylum law.

These laws require asylum seekers to prove they have been persecuted due to their religion, race, nationality, or political views. There is a fifth category as well: “membership in a particular social group.” This one is much more open to interpretation and has allowed some Central Americans fleeing gang violence and domestic abuse to win asylum. It was already incredibly difficult for them to do so, but last month, Attorney General Jeff Sessions cracked down further, announcing that domestic abuse and gang violence will no longer be grounds for asylum in most cases.

As the evening wound down, I asked Powers how many of the people she met with were likely to be able to stay in the United States. She paused before saying she wouldn’t be making the trips to Port Isabel if she thought parents didn’t have a chance. “I prefer to be optimistic,” she says. But she also knew she couldn’t represent everyone. An asylum case requires dozens of hours, and as much as she’d like to, she can’t drop everything to take on 11 new clients. It was still unclear which parents she might represent when we parted ways, before Powers headed back to Port Isabel for her next day of work: Wednesday morning.

On Wednesday afternoon, Mother Jones filmmaker Mark Helenowski and I drove to Port Isabel to meet with Powers before she headed to the airport. The only signs of life were two turkey vultures that held vigil along the road. Powers stood outside the detention center, the wind providing occasional relief from the stifling heat, and described learning that a group of parents had failed to pass their “credible fear” interviews, bringing them one step closer to deportation.

I asked her again about the man who plans to leave his children behind if he is ordered deported. She closed her eyes, took a deep breath, and gathered herself. He had told her the day before, “I’m dead if I go back, but I want my children to be here and be safe.”

“It was a no-brainer for him,” Powers says. “He had the answer.”

Powers went back to work in Houston and, two days later, flew to New Jersey to visit an office she had opened in Hackensack in April to serve another large immigrant community in need of assistance. Far removed from the intensity of Port Isabel, she had a few days to reflect on her experience. We talked about how Sessions’ decision could affect a woman she met who had fled domestic abuse. The woman was separated from her husband because he drank heavily, acted violently, and had multiple affairs, and Powers remembers the woman saying the judge blamed her by citing her “duty to be a woman.” Finally, the woman fled with her 12-year-old child, from whom she is now separated. “She’s doing everything we would expect her to do: file a police report, go to court, stand up for herself.” She would have had a great asylum case before Sessions’ decision, Powers says with some frustration. Now, how her case will ultimately be judged remains unclear.

Powers mentioned three other cases that stuck with her. One involves a mother who saw someone fleeing a crime scene and realized the same person must have committed other crimes—not just a petty crime, Powers tells me, but “a series of murders.” The perpetrator threatened her, disappeared for a while, then returned with additional threats. When she told the police what she knew, they said they were already aware of who he was. “There’s some gruesome details, like really gruesome details,” Powers says, “and unfortunately, I have a very visual mind. Even though I didn’t see it, I feel like I’ve seen it.”

There is also the father who has been separated from his wife and two children. His wife is in one detention facility with the youngest child, who is about three years old, while their older son, who is not yet nine, was placed in a separate facility. Powers says the family fled on a moment’s notice; the father was being targeted because he had political information that placed him at risk. The third case Powers mentioned involves a woman who was harmed by the police. “They have to be fighters,” Powers says. She believes this mother will have the wherewithal to make it through her asylum case, despite what appears to be a systematic effort by the Trump administration to make people fleeing persecution give up.

Those fleeing oppressive countries face another challenge, Powers notes, which is a psychological one: Opening up to government officials is complicated when someone has fled a country where there is abundant reason not to trust people in uniforms. Now, in the wake of Trump’s family separation policy, asylum seekers must share the most intimate details of their lives with the people who “just took all their children away from them.”

Some of the people Powers met said they were told—falsely—that their children would be returned to them after the usually brief trial for crossing the border without authorization. Goodwin says parents at Port Isabel were assured they would be released after passing the credible fear interviews that establish there is a significant chance they will be persecuted in their home countries and allow potential asylum claims to proceed. “That’s not what [ICE] is doing,” Goodwin adds. “They’ve—across the board—set no bond.” It means that lawyers will have to ask an immigration judge to set bond. That will take about a week to get scheduled, and even if they succeed, ICE can appeal the judge’s determination. (Mother Jones reported on Sunday that ICE is also denying bond to separated parents at the T. Don Hutto detention center near Austin.)

The decisions parents will have to make in the coming weeks and months are not as simple as staying or leaving as a family. Children and parents may have their own cases that are adjudicated independently. The outcomes will not always be the same.

Listen to reporter Noah Lanard explain how the government appears to be using bond denials to prolong family separation at the border in this episode of the Mother Jones Podcast: