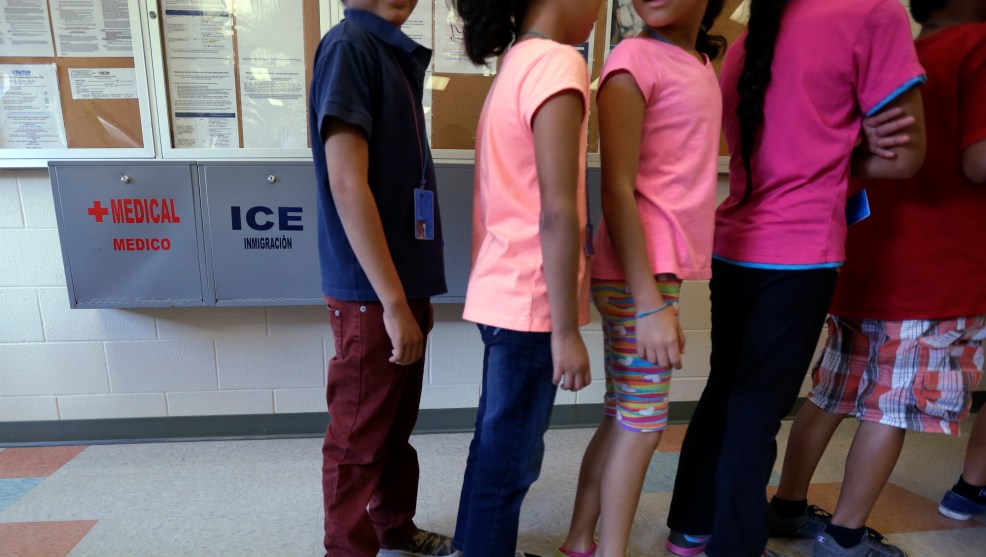

Detained immigrant children line up at the Karnes family detention center in Texas in 2014.Eric Gay/AP

The Trump administration is planning to withdraw from a decades-old settlement agreement that prevents it from keeping children in family detention for more than about 20 days. The proposed rule announced on Thursday would allow the Department of Homeland Security to detain thousands of families indefinitely while their immigration cases proceed, although it is almost certain to be challenged in court.

The 1997 Flores settlement agreement requires the government to hold children in state-licensed child care facilities. The government’s three family detention centers do not meet that standard. As a result, Dolly Gee, the federal judge who oversees the Flores agreement, ruled in 2015 that the government must release children from family detention centers after about 20 days. Her decision was later upheld by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The Trump administration wants to circumvent Flores’ state-licensing requirement by creating an “alternative” federal licensing scheme. That would allow Immigration and Customs Enforcement to operate what the government claims would be Flores-compliant family detention centers where families can be held indefinitely.

The proposed rule states that DHS is aware that its plan could result in longer detention times for children, but DHS is unaware of “how much longer individuals may be detained.” As a result, it is unable to estimate how much the plan will cost.

The proposed rule does not take effect immediately, and the public will have 60 days to comment on it once it is published in the federal register on Friday. If the rule is challenged in court, the case would be heard by Gee.

The announcement from DHS and the Department of Health and Human Services comes less than three months after President Donald Trump issued an executive order to end his family separation policy. That order put the administration in a bind, since ICE could not hold parents indefinitely without separating them from their children. The administration did not want to return to the old practice of releasing families while they were awaiting hearings, but Flores prevented it from holding children with their parents for more than about three weeks. The proposed rule emphasizes the importance of “keeping families together” during their immigration cases.

Wendy Young, the president of the advocacy group Kids in Need of Defense, said in a statement that children and adults have suffered “horrific treatment” in federal custody for decades. “It is outrageous that, after tearing thousands of children from their parents, the Administration is focused not on their reunification but on condemning other children to harsh treatment,” she said.

Trump’s executive order ending family separation asked Gee to amend the Flores agreement to allow for indefinite definition. She quickly rejected that request. “Defendants seek to light a match to the Flores Agreement and ask this Court to upend the parties’ agreement by judicial fiat,” she wrote.

It is unclear why she would be more sympathetic to the government’s alternative licensing plan. But the timing of the public comment period, which ends on the day of the November midterm elections, could help fulfill Trump’s goal of keeping immigration on the minds of his base voters in the lead-up to the elections.

DHS states that the rule will not cause most detained children to spend any additional time in family detention. That is because migrants who cross the border without authorization are eligible to be released on bond by an immigration judge if they pass a credible fear interview that establishes a “significant possibility” of persecution in their home country. Of the roughly 17,000 children at family detention centers who went through the credible fear process in the last fiscal year, about 89 percent passed, according to the text of the proposed rule. About 99 percent of those children were released from detention. The rules state that 20,606 children were sent to family detention centers that year.

The rule would primarily affect children who do not pass credible fear interviews or those whose parents have outstanding deportation orders. DHS estimates that about 2,787 children would have been detained longer in 2017 because of the rule.