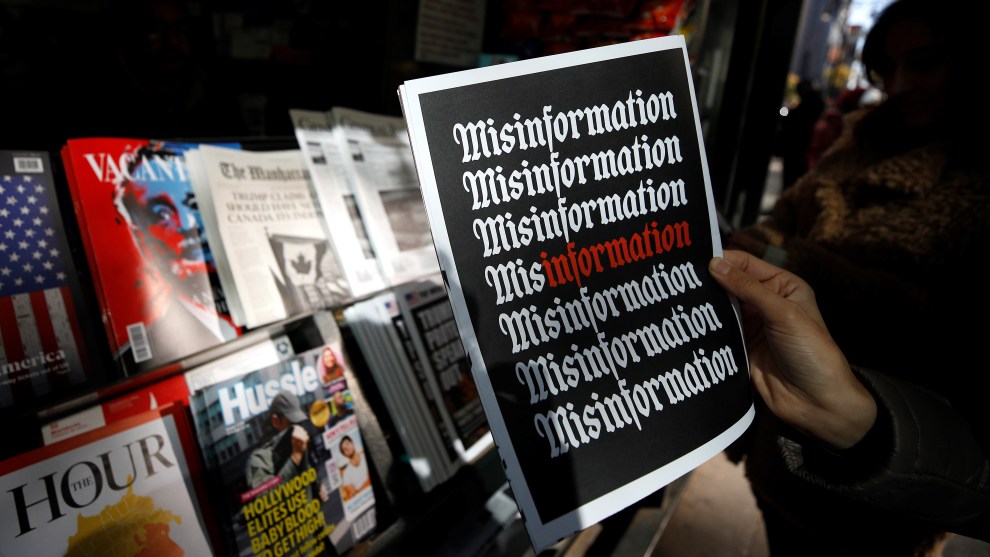

Photo by Chesnot/Getty Images

Chris Hughes, who helped Mark Zuckerberg co-found Facebook out of a Harvard dorm room fifteen years ago, now thinks the company is a “powerful monopoly” that must be split apart.

“The government must hold Mark accountable,” Hughes wrote in a op-ed published Thursday in The New York Times. “Mark’s power is unprecedented and un-American. It is time to break up Facebook.”

In his essay, Hughes criticized regulators for not doing more to stop Facebook from growing into a monopoly and Zuckerberg for his attempts to thwart them. The former Facebook co-founder suggested that federal antitrust actions against IBM, AT&T, and Standard Oil provide instructive models for how regulators can curb Facebook’s massive reach.

“Mark’s influence is staggering, far beyond that of anyone else in the private sector or in government,” Hughes wrote. “He controls three core communications platforms—Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp—that billions of people use every day.”

Hughes said that the Federal Trade Commission’s decision to let Zuckerberg acquire Instagram and WhatsApp was its “biggest mistake” in failing to rein Facebook’s power. He recalled how the company, years ago, had struggled to adapt to users shedding desktops and increasingly accessing the internet with phones. Facebook hadn’t gotten a lock on mobile yet, and Zuckerberg responded by buying companies that had—and the FTC willingly approved it.

In his op-ed, the former Facebook co-founder argued the FTC should take action and retroactively spin-off companies owned by Facebook into separate entities. But Zuckerberg might already be taking steps to head this off: Facebook has moved to more closely integrate WhatsApp and Instagram, making it more difficult for regulators to break units off from the multibillion-dollar company.

Hughes also noted other efforts by the company to stymie competition.

“When it hasn’t acquired its way to dominance, Facebook has used its monopoly position to shut out competing companies or has copied their technology,” he said, referencing Facebook’s decision to block the defunct Twitter-owned video app Vine from accessing Facebook users’ friends, and the company’s appropriation of Snapchat’s core features of disappearing photos and video.

“Investors realize that if a company gets traction, Facebook will copy its innovations, shut it down or acquire it for a relatively modest sum. So despite an extended economic expansion, increasing interest in high-tech start-ups, an explosion of venture capital and growing public distaste for Facebook, no major social networking company has been founded since the fall of 2011,” Hughes wrote.

A number of other former high-profile Facebook employees and executives have criticized the company over the past several years, including former President Sean Parker and former senior executive Chamath Palihapitiya. Leaders of the companies Facebook has acquired, including WhatsApp’s Brian Acton, have also lambasted the company.

On the 2020 presidential campaign trail, Democrat Elizabeth Warren has also called for regulation and the breaking up of large tech companies including Facebook.

In a March Washington Post op-ed, Zuckerberg welcomed some form of regulation of his company. Hughes argued in his own op-ed that the move represented a preemptive attempt to direct the conversation to new rules and regulations, and away from any antitrust action that might break up Facebook.

“If we do not take action, Facebook’s monopoly will become even more entrenched,” Hughes warns. “With much of the world’s personal communications in hand, it can mine that data for patterns and trends, giving it an advantage over competitors for decades to come.”