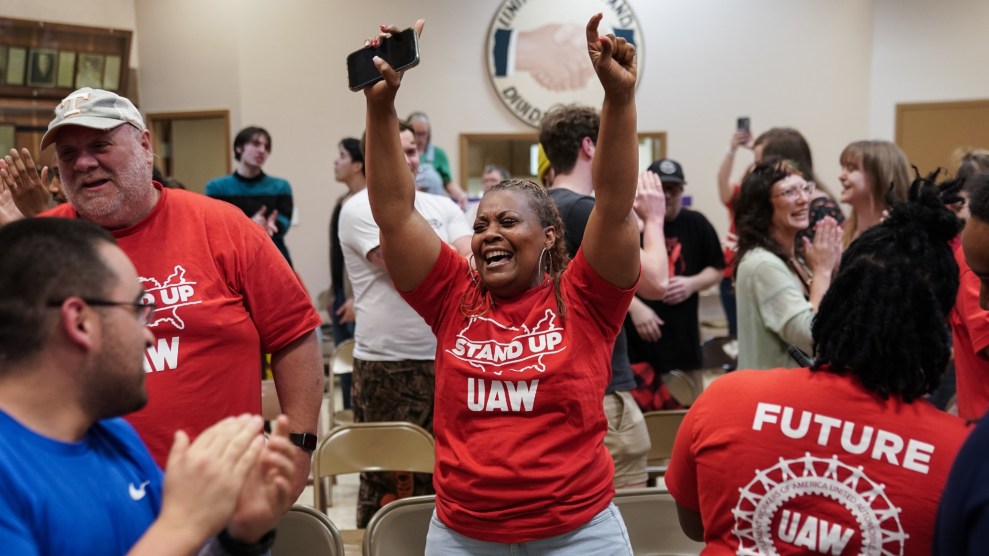

Acting Secretary of Homeland Security Kevin McAleenan and El Salvador's Minister of Foreign Affairs Alexandra Hill sign a migration agreement on Friday in Washington, DC.Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP

On Friday morning, the Department of Homeland Security tweeted a message featuring a gif of Kermit the Frog banging away at a typewriter, accompanied by the text, “DHS beat reporters are gonna be busy today.” The big news is that the United States has reached a deal that could allow it to return asylum seekers stopped at the border to El Salvador, one of the world’s most violent countries.

The use of a Kermit gif to preview yet another potential abandonment of America’s commitment to protecting people fleeing persecution is only slightly surprising at this point. Over the past year, the Trump administration has waged an unprecedented campaign to dismantle the US asylum system. After a long string of defeats in court, it has celebrated recent victories with the unrestrained glee of a sports fan whose team is pulling off an upset. The fact that people may die because of its wins goes unstated.

It is still unclear if and when the United States would force people stopped at the border to seek asylum in El Salvador. At a press conference on Friday, Acting DHS Secretary Kevin McAleenan said that was “one potential use” of the agreement but did not offer a timeline for when that might happen. In July, the United States reached a similar deal with Guatemala. McAleenan said in late July that he expected the United States to start sending asylum seekers to Guatemala in August, but that still isn’t happening.

The goal of sending back asylum seekers who pass through El Salvador would not be to strengthen protections, but to make the idea of seeking asylum in the United States so unappealing that fewer people will even try. More than 80,000 Salavadorans, many of whom are fleeing gangs like MS-13, have been stopped at the US-Mexico border this fiscal year. The country’s murder rate has declined sharply in recent years, but still remains among the world’s highest. In 2018, the country’s murder rate was 51 per 100,000 people, roughly 10 times higher than in the United States.

Imagine being a Nicaraguan escaping President Daniel Ortega’s oppressive regime. You know the United States is far safer and offers better opportunities for a new life. So you make your way up through Central America and Mexico—risking your life along the way—to ask for asylum at the US-Mexico border.

Once at the border, you’re told you’ll have to wait for weeks or months in dangerous border cities thanks to the Trump administration’s practice of capping the number of people who can request protection each day. Once you’re done waiting, you might be sent back to Mexico while your case is pending, since the Trump administration has now forced nearly 50,000 asylum seekers to stay south of the border while awaiting adjudication. Or, under the new agreement, you could potentially be sent back to El Salvador after all those months of hardship.

Would you try for asylum in the United States knowing all that? Probably not. That is exactly what the Trump administration is banking on. The goal is to minimize the number of people who see the United States as a viable safe haven.

How exactly the new agreement would work is hazy. Would asylum seekers from Africa and Asia who pass through Latin American on their way to the border be returned to a country where they don’t speak the language? Or, like the deal reached with Guatemala in July, would only other Latin Americans be sent to El Salvador?

What, if anything, El Salvador is getting in return is another question. The country reportedly wanted the Trump administration to reconsider its move to end temporary protected status for Salvadorans, a protection that allows nearly 200,000 Salvadorans already in the United States to remain there due to the danger back home. The administration refused to negotiate on that point.

At the press conference, Salvadoran Foreign Minister Alexandra Hill did not do much to dispel the notion that asylum seekers from other nations wouldn’t be safe in her country. “We are working every single day to try to solve this issue of people who by various reasons—reasons of insecurity or reasons of death threats—are forced to leave our country,” she said in English before adding, “El Salvador has not been able to give our people enough security or opportunities so that they can stay and thrive in El Salvador.”

Hill moved on to a point that is rarely made by the government with which she’d just signed an agreement. “When we talk about illegal or forced migration, sometimes we lose the concept that they are human beings,” she said. “These are human beings that are suffering. Human beings that are trying to find a better future for them and their children.”