Credit Image: © Renee Jones Schneider/TNS via ZUMA Wire

Election security has garnered a lot of attention in the wake of Russian’s 2016 influence operation. In particular, concerns over the reliability and integrity of voting machines—long a subject of considerable attention in hacker and tech circles—has made its way into the mainstream, prompting many states and local jurisdictions to upgrade equipment.

But the vendors who make, sell, and service the equipment that make elections work—the voting machines, voter registration databases, ballot programming software, and electronic poll books—largely fly under the radar with little oversight, according to a new report from the Brennan Center, leaving United States elections unnecessarily vulnerable to foreign interference.

“There is almost no federal regulation of the vendors that design and maintain the systems that allow us to determine who can vote, how they vote, or how their votes are counted,” write coauthors Larry Norden, Christopher Deluzio, and Gowri Ramachandran in their new report, “A Framework for Election Vendor Oversight,” published Tuesday. The trio notes that even though such systems were designated as “critical infrastructure” by the federal government in the wake of 2016, the vendors who design and sell them face less regulation than those who produce colored pencils.

“There’s been little attention paid to vendor practices, and election system vendors are responsible for a big part of whether or not our elections are secure,” Norden told Mother Jones ahead of the report’s release. Private companies that work in other critical areas face a bevy of regulation and have to meet a variety of standards, he said, and election vendors should too.

Currently, only “voting systems” are tested and certified by the Election Assistance Commission, a federal agency created in the wake of the 2000 presidential race recount in Florida. The standards were adopted in 2005 and cover the hardware and software that prepare voting machines and ballots, test them, record and count votes, report results, and produce audit data. Although the vast majority of states require voting equipment to pass this certification, the process is voluntary. That level of independence has its roots in America’s constitutionally proscribed history of having states control their own elections.

But an even bigger issue for the report’s authors is that today’s voluntary standards fail to place key requirements on vendors, such as background checks for personnel, transparency in ownership, and approaches to supply chain security. “The threats posed by foreign influence over a US election vendor—including the heightened potential for foreign infiltration of the vendor’s supply chain or knowledge of client election officials’ capabilities and systems—should be obvious,” the authors wrote.

The authors suggest a few fundamental shifts, including greater funding and authority for the EAC to address such concerns. Despite the likelihood of increasingly sophisticated cyber attacks, the agency’s 2019 budget was just $9.2 million, down from $18 million in 2010. While the report says the EAC could require more of vendors on its own with current resources, the report calls for more funding to help the agency to expand its cybersecurity expertise, and for Congress to exercise greater oversight of its work, rather than, as Republicans have several times, try to kill it.

Norden says local election officials would be able to make better decisions if vendors had to provide more information about their cybersecurity practices, ownership structure, or the way they work with subcontractors.

“I don’t mean to bash the vendors, I just think everybody would be better off if there were national standards and there was transparency about what they were doing,” Norden said, pointing to a situation in 2016 where VR Systems, a Florida-based provider of electronic registration books and other election services, was apparently hacked—an incident where the details and repercussions are still not publicly clear.

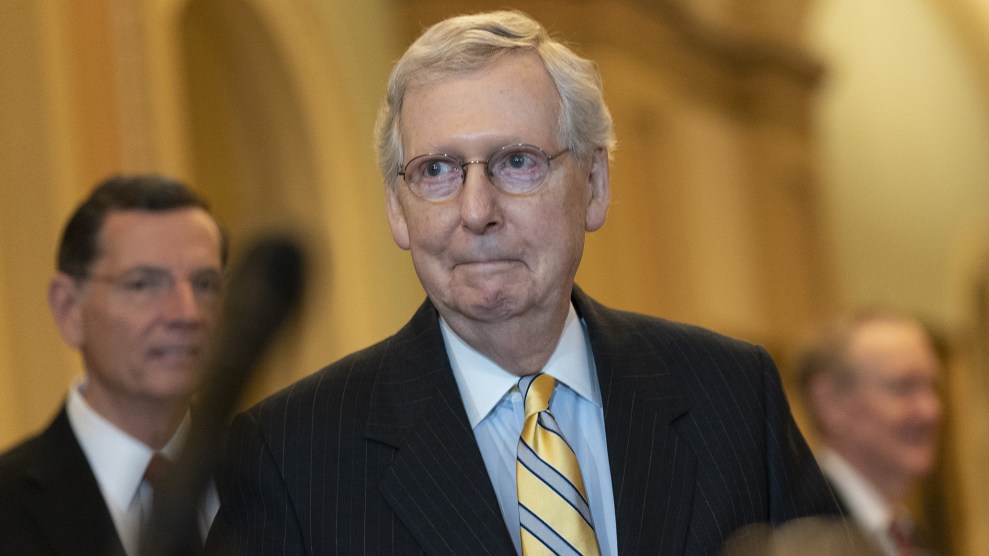

Norden says that other election security proposals—some of which include proposals reflected in the report—have stalled in Congress at the feet of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, a Kentucky Republican who says that states should have most of the control and responsibility over election security.

“Unfortunately, what we’ve learned with Congress around these issues is that you need a crisis before they’re willing to act,” Norden said. He pointed to last week’s indictment of two former Twitter employees accused of spying for Saudi Arabia while on the job as a very real and recent example of how technology companies can be penetrated by foreign interests.

“I hope that we don’t have a situation like that where we find out that we have people working at one of the vendors that was also working for a foreign government,” he said. “It’s not an impossible thing to imagine. We have too many precedents to think that couldn’t happen given how important our election vendors are, and given how damaging their attack could be to our election security. So I hope we don’t have to get to that point.”