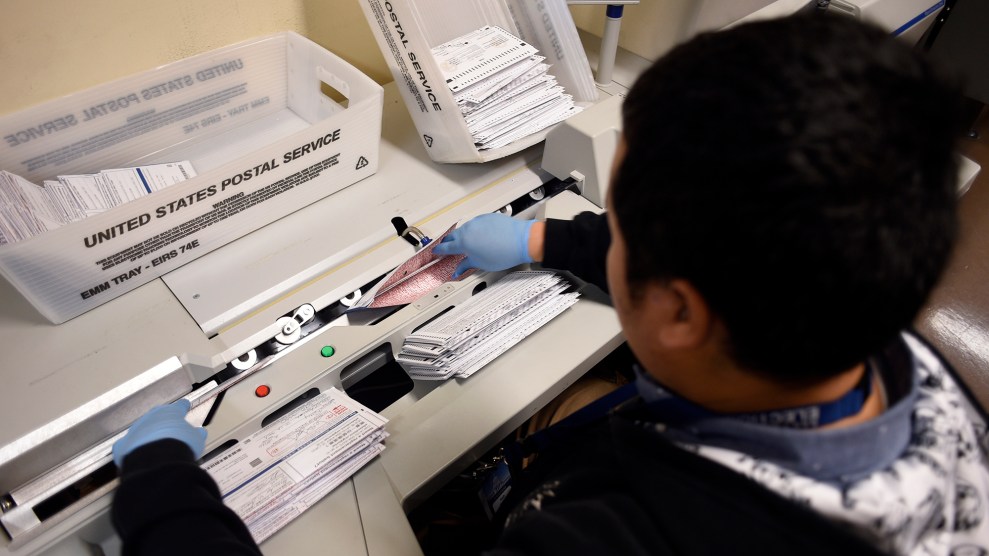

Mark Hertzberg/Zuma

As the country grapples with how to safely conduct elections amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, calls for increased access to vote-by-mail have grown loud and persistent. While some form of voting by mail is already available in each state with varying degrees of ease, the push to make it more widely accessible, even against the backdrop of the pandemic, remains mired in partisan politics and opposed by Republicans.

But the actions of one small town just north of Milwaukee show how local officials—given the right resources, legal framework, and attitude—can take simple steps to encourage and empower large numbers of voters to cast ballots from the safety of home. Three weeks before thousands of Wisconsinites were forced to trudge to polling places on April 7 in spite of a statewide “safer-at-home” order, Paul Boening, the village manager of suburban Whitefish Bay, had already concluded that this wasn’t going to be a normal election. On March 16, Boening and the village board met to make a plan for the burgeoning public health crisis, and decided that access to public buildings would be shut down the next day. On that last day the village administration office was open, he says, the vast majority of residents stopping by were there for the same reason: They wanted to fill out an application for a mail ballot.

The in-person interest convinced Boening and the board to look ahead and automatically send each of the town’s roughly 10,000 registered voters an absentee ballot application. “We wanted to be proactive,” he told Mother Jones on Tuesday. “We didn’t want to get into a situation where we were a day or two from the election and there were a number of residents still scrambling tying to figure out how to get a ballot, or for us to be able to get them one in time.”

While such mailings are a relatively common tactic for political parties or campaigns looking to drive turnout in a particular community to boost their causes and candidates, this was the village’s own decision in reaction to an unprecedented situation. And, according to data analyzed by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, the effort paid off: Roughly 60 percent of Whitefish Bay’s voters followed through and ended up voting via mail ballot, the most of any village or city in Wisconsin and almost double the statewide average of about 34 percent. In 2016, when both Democrats and Republicans had contested presidential primaries on Wisconsin’s ballot, Whitefish Bay, a relatively affluent community fronting Lake Michigan, recorded 73 percent turnout. Stacking that up against this year’s numbers, Boening says that “given the fact that there’s a global pandemic, we’ll take it.”

Whitefish Bay was one of seven smaller communities north of Milwaukee—all in Milwaukee County—that sent out a joint letter urging people to apply for a mail ballot. While final figures aren’t yet known, at least one of the other communities that joined the push, North Shore village, also saw a huge returns on the effort, with 59 percent of registered voters there voting via mail ballot, according to the Journal Sentinel. Boening estimates that “just a few hundred” voters ended up voting in person on April 7 in Whitefish Bay.

“That’s what our goal was,” Boening said. Without the Republican state legislature agreeing to delay the election, village officials figured they would have to open and staff their usual four voting locations. “We wanted to try to limit the foot traffic to comply with the guidance from public health officials. We knew that every resident who voted by mail was one less person who would be coming to the polls on Election Day.”

Whitefish Bay has some advantages that made the effort more feasible that it might be elsewhere, including Wisconsin laws that allow anyone, without any kind of excuse, to vote absentee. With just 10,000 registered voters, Boening estimated it cost the town just a few thousand dollars. “We, along with every other government agency is going to be expending funds that we did not anticipate” in responding to the virus, he said. “Whether that’s first responder overtime, or the cost to acquire PPE, and I would say the voting mailing was no different.”

Boening also pointed to the village’s track record of high election turnout and engagement, which he credited in part to its relatively small geographic footprint which “lends itself to community and belonging.” Boening also said the small town’s political traditions—the village board is nonpartisan and mostly concerns itself with core services—made it easier to act without considering any broader statewide or national political interests. Decisions were made, he says, from a “public health perspective, and there was zero pushback whatsoever, and it was great to have that support from the governing body.”

Boening said that election staff is already preparing for the state’s next election, which will be in August, and after that, for November.

“I would just hope that everyone takes a step back and really takes a hard look at how things went in April,” he said. “It doesn’t seem like COVID itself is going away…Now is the time to begin planning for how those elections should take place and not waiting until it’s too late.”