Yasushi Nagao/Mainichi Shimbun/Bettmann/Corbis via Getty

Donald Trump’s attack on the election has ignited a firestorm of fundraising by his campaign and allied groups to finance efforts to hunt out supposed fraud. On Monday, Jenny Beth Martin, co-founder of Tea Party Patriots, asked her Twitter followers to contribute to an “election integrity” project run by Matt Braynard, a GOP operative who was looking for $500,000 to underwrite his endeavor. As a former data specialist on Trump’s 2016 campaign, Braynard had experience in this field. But Martin didn’t mention one notable project Braynard not long ago pursued: creating a literary journal that celebrated a real-life political assassin.

Braynard was the leader of the data team for Trump’s 2016 campaign until leaving in March 2016. At the time, Politico reported that neither Braynard nor Corey Lewandowski, then the campaign manager, would explain the departure—a move that left some campaign officials unable to access data files. (Braynard tells Mother Jones that he was laid off over a “minor HR dispute” with Lewandowski.) According to an online bio, Braynard had worked as a political analyst at the Republican National Committee and for GOP pollster Frank Luntz. After exiting the Trump campaign, he formed a nonprofit called Look Ahead America to increase conservative voter turnout.

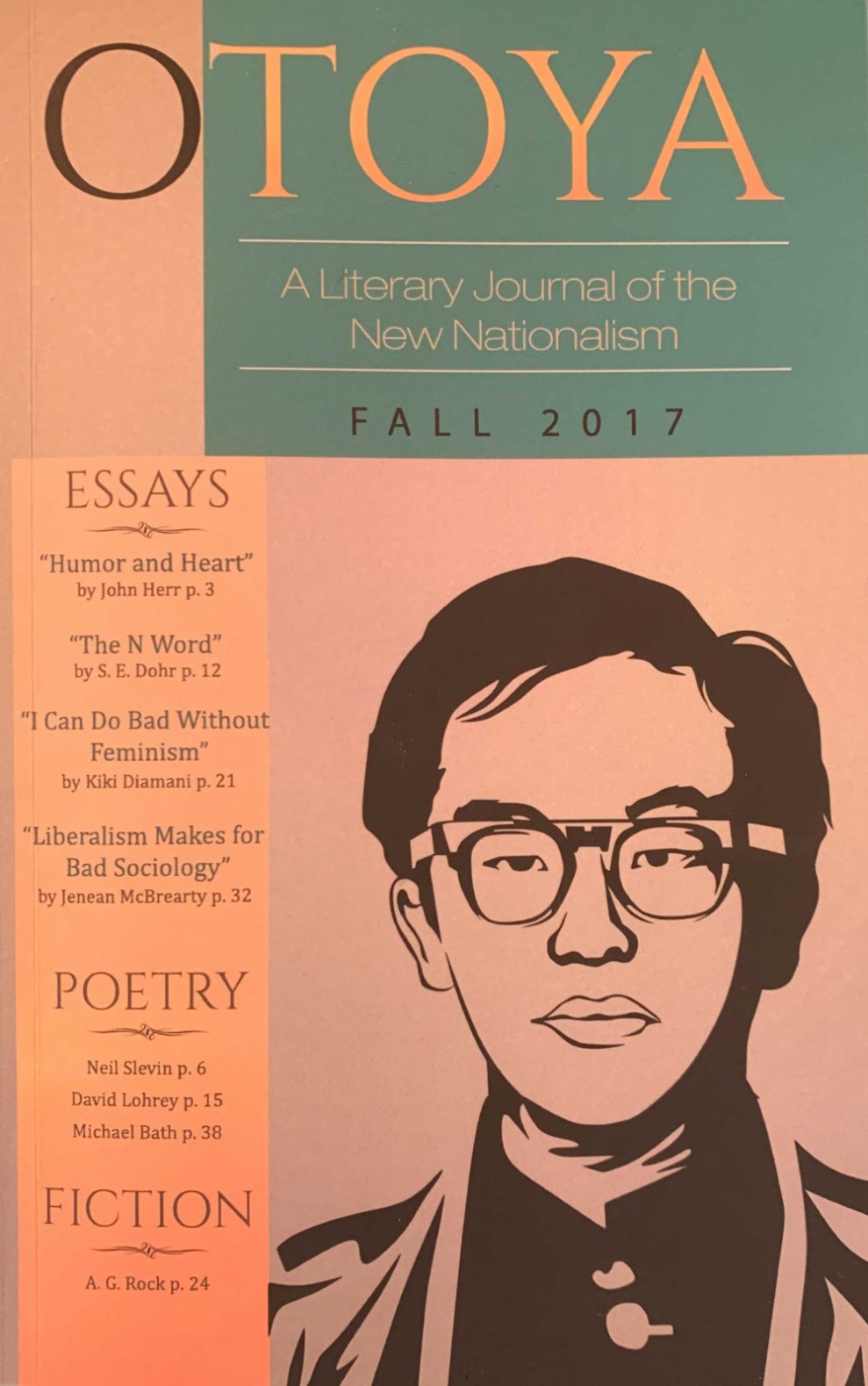

That online bio also notes that Braynard is an “award winning short fiction writer.” In that vein, he founded a literary magazine in 2017 as part his MFA coursework at Columbia University. Called Otoya, it billed itself as a “Literary Journal of the New Nationalism.”

The publication, Braynard explained in a brief editor’s note, was named in honor of Otoya Yamaguchi. In 1960, Yamaguchi, a 17-year-old rightwing ultranationalist in Japan, brutally murdered Inejirō Asanuma, a member of parliament and the chairman of the Japan Socialist Party, at a televised election debate. Yamaguchi stabbed Asanuma with a short samurai sword. The image capturing the horrific moment became one of the most famous press photos of the 20th century. After he was arrested, Yamaguchi committed suicide and became a fallen hero of the Japanese far right.

A drawing of Yamaguchi graced the cover, as Braynard’s note described the murderer as a nationalist hero who heroically killed a communist. He pointed out that Yamaguchi shared a birthdate “with another great patriot who put bayonets through the enemies who threatened his nation, George Washington.”

In an interview this week, Braynard explained his admiration for Yamaguchi. Braynard recalled visiting Cambodia, where he says he saw piles of skulls of victims who had been murdered during the bloody reign of the Khmer Rouge. “I think [Yamaguchi] may have prevented the same thing from happening in his own country,” Braynard says. “He should be memorialized and remembered.” Only one issue of Otoya was published.

Braynard’s voter fraud project was set up days after the 2020 election, when he established a GoFundMe page seeking half a million dollars to uncover purportedly illegitimate votes in swing states using Social Security and change-of-address databases. GoFundMe removed the page, criticizing it for attempting “to spread misleading information about the election.”

He relaunched at GiveSendGo—which bills itself as the “#1 Free Christian Crowdfunding Site”—where, as of Friday, he had raised more than $580,000. His fundraising page states, “The funds from this campaign will be received by Matt Braynard.” But it also notes, “Matt Braynard will personally receive zero dollars.” Braynard says that all the money he collects will be spent on his research and that he will not be pocketing any.

On his Twitter feed, Braynard provides updates on leads his team is chasing and has suggested that having met his original funding goal, he may ask for more. He tells Mother Jones he has already spent about $500,000 acquiring various databases and hiring call centers to contact people who he suspects may be connected to voting irregularities. He estimates he needs another $300,000: “Every day we find more ways to spend money.”

The New York Times has reported that election officials across the country say there is no evidence of significant voter fraud. Yet Braynard contends the matter remains open, as his team conducts up to six different analyses of voting in each of six swing states. Braynard claims to have found instances of people casting ballots in two different states, including 631 cases in Pennsylvania—even if verified, not remotely enough to change the results.

Braynard still insists this finding is significant. “If there is an organized attempt at voter fraud, we will only detect a few cases,” he says, adding that he hopes his research may “bring enough pressure” to encourage judges to order remedies including recounts or audits. He notes he’s been sharing his research with Trump’s legal team, and “they are asking us to do more.”

Braynard maintains that he “didn’t walk into this with any preconceived notions” regarding the possibility of fraud in the election. He just wants to know, “is this really a clean election?” Asked if he expects his findings to be trusted, given that he’s a Trump fan, he replies that anyone will be able to check his figures. He adds, “And I am the biggest fan.”