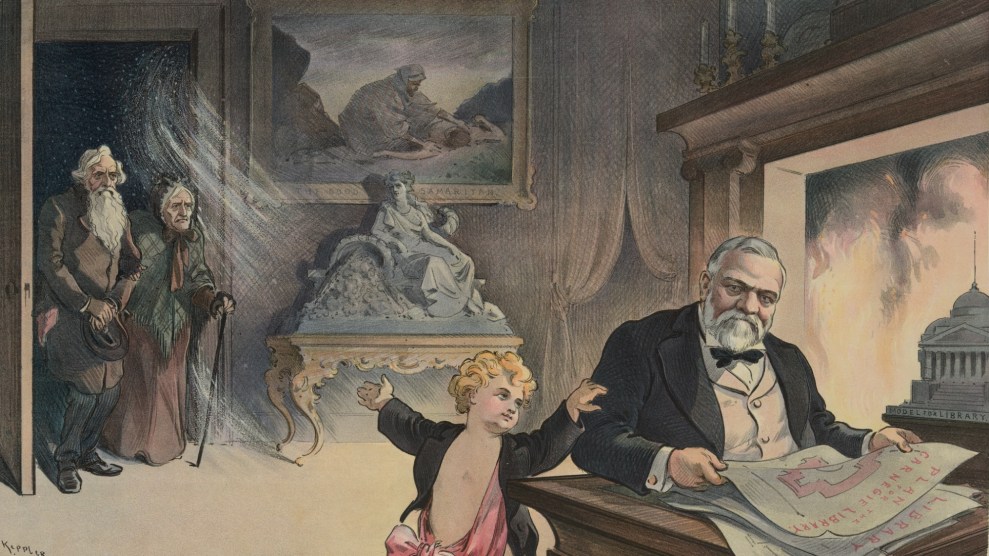

Udo Keppler/Library of Congress

As an American who attended college in Canada, I assumed Boxing Day was the day you returned unwanted Christmas gifts and bought other stuff on sale. I wasn’t entirely wrong about the second part, but my grasp of the holiday was notional at best. So to ask a question I should have posed more than a decade ago: What is Boxing Day?

This much we can say: Officially, it’s a bank holiday after Christmas that’s observed in the United Kingdom and other parts of the Commonwealth, and—in normal times—a chance to watch sports, go to the pub, and shop.

But how exactly Boxing Day came to be is disputed, though there is general agreement that the holiday is charitable in origin.

One theory about the etymology of the day’s name is that churches would collect boxes of alms in the run up to Christmas, and finally unbox and distribute them to the needy on Saint Stephen’s Day, which falls on December 26, who was known for his service to the poor.

As National Geographic explained, another theory focuses on workers going door to door in search of yearly Christmas tips known as “boxes.” A poem in “The Comic Almanack” published in 1843 describes milkmaids, bakers, butchers—alongside “scavengers” and “turncocks”—showing up to plead for their Christmas box. The Scrooge-ish author imagines that, having siphoned off some of his wealth, they “all get drunk, and strip to fight/To prove it is a Boxing Day.”

Finally, Boxing Day may have evolved from employers in Victorian England giving their servants boxes of money, food, and gifts after spending their Christmas waiting on their employers. The servants would then get December 26 off to spend with their families, as the aristocrats enjoyed high tea and leftovers without them. As Mrs. Beeton’s Everyday Cookery, a Victorian guide to homemaking, recommended in 1872, servants should get a Christmas box on their final quarterly payday of the year: December 25. The goal was to “encourage good service and promote kindly feelings.”

With that background, its fair to place Boxing Day inside of a grander, year-round tradition, observed all the world over: the rich trying to appease poorer people without parting with a meaningful share of wealth.

This year, Amazon announced $300 holiday bonuses for full-time employees that it will cost the company $500 million. That’s less than one percent of the wealth Jeff Bezos has amassed during the pandemic. In Washington, after months of back and forth over COVID relief—a delay that’s left families destitute and desperate—Mitch McConnell allowed stimulus spending to go through, perhaps in the hopes of promoting the kindly feelings of Georgia voters who will soon determine whether his Republicans hold the Senate, and he remains majority leader.

His $600 Christmas boxes should be arriving any day.