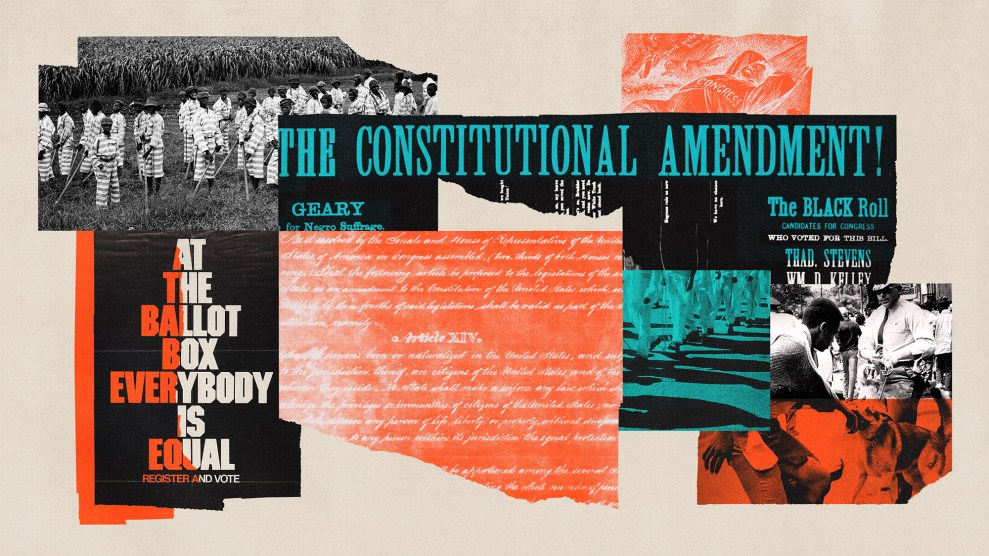

Mother Jones illustration; Getty

In 2013, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote the opinion gutting Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which required that states with a long history of discrimination had to approve their voting changes with the federal government. That ruling led to a wave of new voter suppression laws in states including Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas.

Roberts justified his position by pointing to the continued existence of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which applies nationwide and outlaws the denial or abridgment of the right to vote on account of race or color. “Our decision in no way affects the permanent, nationwide ban on racial discrimination in voting found in Section 2,” he wrote in Shelby County v. Holder.

But now, in two Supreme Court cases from Arizona that will be heard on March 2, Republicans are trying to kill what remains of the VRA. Influential Republicans at the state and federal level (including Ted Cruz and Mitch McConnell in an amicus brief) have asked the court’s conservative majority to weaken Section 2 or strike it down all together. If they succeed, the VRA would provide little to no protection to voters of color facing an onslaught of new GOP voter suppression efforts across the country, where more than 250 bills restricting voting access have been introduced in 43 states in the past two months.

“This is a time where we are in desperate need of the Voting Rights Act,” says Myrna Pérez of the Brennan Center for Justice, “where it is unmistakable that some politicians are reacting with restrictions when they see voters voting, instead of choosing to compete for their vote.”

The GOP’s push to weaken Section 2 dates back more than 40 years—and Roberts was a key foot soldier in that effort.

In the early 1980s, decades before he became chief justice, Roberts served as a young lawyer in Ronald Reagan’s Justice Department. Before Roberts arrived at the DOJ, civil rights groups had filed suit against Mobile, Alabama, where a Black candidate had never been elected to the city council even though Black people comprised a third of the port city’s population. The lower courts said that the city’s election system discriminated against Black voters, but in April 1980 the Supreme Court sided with Mobile, ruling that “racially discriminatory motivation is a necessary ingredient of a Fifteenth Amendment violation.” That meant smoking-gun evidence of intentional discrimination, which was very difficult to find, was needed to strike down laws or overhaul elections systems that blocked people of color from voting or winning elections.

Democrats and civil-rights groups were outraged. The Democratic-controlled House of Representatives amended Section 2 of the VRA so that voters of color only had to show that a voting law or election system had the result of discriminating against them, not the intent, which was much easier to prove.

That set up a major battle with the Reagan administration, which wanted to keep the intent requirement for Section 2. Roberts became the point person for the Justice Department’s push to constrain the VRA. “Violations of Section 2 should not be made too easy to prove,” he wrote in 1981, in one of 25 memos opposing the House bill, “since they provide a basis for the most intrusive interference imaginable by federal courts into state and local processes.” (I tell this story in detail in my book Give Us the Ballot.)

Roberts lost that fight when the US Senate overwhelmingly extended the VRA in 1982 for another 25 years and included expansive language protecting the right to vote. But now, four decades later, Republicans are once again taking aim at Section 2, trying to roll back critical voting rights protections for voters of color.

The cases, which the Democratic Party brought against the state of Arizona and the Arizona Republican Party, concern two voting restrictions passed by the GOP-controlled state legislature—a ban on collecting mail-in ballots and a law throwing out votes cast in the wrong precincts—that were struck down by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in January 2020 for discriminating against Native American, Latino, and Black voters.

From 2008 to 2016, Arizona threw out more than 38,000 ballots because voters showed up to the wrong voting precinct, even though their votes for statewide offices should still have been valid. Arizona rejected more out-of-precinct ballots than any other state—a rate 11 times higher than the state with the second-most rejections, Washington. In 2016, American Indians, Latinos, and Black voters were twice as likely as whites to have their ballots thrown out for this reason.

Similarly, a law preventing anyone but a family member or caregiver from returning a mail-in ballot (what Republicans call “ballot harvesting”) also discriminated against Native Americans and Latinos, the Ninth Circuit found, since those communities more often lack reliable mail service and live greater distances from polling locations, requiring assistance to return their ballots. When the law was first passed in 2011, Arizona’s elections director told the Justice Department it was “targeted at voting practices in predominantly Hispanic areas.”

But the case is much bigger than two relatively obscure voting restrictions in Arizona. Republicans want to turn it into a vehicle to exempt all manner of new voter suppression laws from being struck down under the VRA. Arizona Republicans, including Rep. Debbie Lesko, who voted to throw out her state’s electoral votes for Joe Biden, are asking the court to rule that “ordinary race-neutral regulations of the time, place, and manner of voting do not violate Section 2.” That would give Republicans a free pass to enact new voting restrictions like voter ID laws, cuts to early voting, and voter roll purges that do not explicitly mention race but in practice disenfranchise voters of color more than white people.

A brief by from Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, which was written by Donald Trump’s lawyer William Consovoy, claims that a discriminatory voting law can only be struck down “when it causes a substantial disparity in opportunities for members of a protected class to participate in the political process and affect electoral outcomes,” which would be an extremely high bar for voters of color to clear before conservative-dominated courts.

And 11 Republican senators, including McConnell, Cruz, and Tom Cotton, have asked the court to strike down Section 2 altogether. “The Ninth Circuit’s sweeping interpretation of VRA Section 2,” they write, “would also render the statute unconstitutional.” The GOP senators warn of “an aggressive wave of litigation aimed at further expanding Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act” that would “threaten legitimate election-integrity laws,” such as stricter voter ID laws, cutbacks to early voting, and rollbacks of mail voting. (Civil rights groups have successfully challenged new restrictions on voting in states like North Carolina and Texas under Section 2.) Essentially, McConnell and his colleagues want Republicans to be able to continue to restrict voting rights unimpeded by the VRA.

The interpretation of Section 2 by these Republicans, writes the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights in its own brief in the case, “would render that provision hopelessly ineffective in combating the new species of vote-denial laws, i.e., laws that make it disproportionately more difficult for minority voters to participate in the political process.”

Given the 6-3 conservative majority, it’s unlikely the court will affirm the Ninth Circuit’s opinion, but it’s possible it could reverse the ruling without further weakening Section 2. It’s also possible the court’s conservative justices could go much further, as some Republicans want, to strike down Section 2 or make it completely toothless. Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch have said that Section 2 should not prohibit racial gerrymandering. And in the run-up to the 2020 election, Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh embraced a radical doctrine holding that voting rules passed by state legislatures cannot be reversed by federal courts.

Tellingly, Roberts—who led the fight to weaken Section 2—is now the most moderate member of the court’s conservative wing. It would be quite something for Roberts to gut Section 5 of the VRA while pointing to the relevance of Section 2, and then kill that part of the law as well. “It would mean the Court not only mothballed Section 5, but dramatically limited the protections under Section 2, which would be a clear statement from the court that voters should not look to it to protect them from racial discrimination in voting,” says Pérez.

At a time when new restrictions on voting are proliferating across the country following Trump’s Big Lie—and when civil rights activists say strong protections for voting rights are more important than ever—the Supreme Court may make it that much easier for GOP-controlled states to undermine the right to vote.