If you grew up listening to your local classic rock radio station, there are probably a few facts about Eric Clapton that have been engrained in your head.

He taught himself to play guitar as a teenager and became the engineer of classic rock hits including “Layla” and “Crossroads.” He’s been a member of more rock groups than you can shake a stick at: the Yardbirds, Cream, Derek and the Dominos, Blind Faith, and the Plastic Ono Band, to name a few. His four-year-old son died after falling from a high-rise window, inspiring the song “Tears in Heaven.”

There are two crucial facts that I didn’t know about Clapton until very recently. One is that “Crossroads” was not an original song but a cover of Delta blues musician Robert Johnson’s “Cross Road Blues,” first recorded in 1936. The other is that, in 1976, Clapton went on a drunken, racist diatribe at a concert, hurling racial slurs about immigrants and arguing that England should be a white country. No one knows Clapton’s precise language, because there are no known recordings of the outburst, but numerous witnesses have recounted the incident, which spurred the “Rock Against Racism” punk movement.

Clapton profited off of the work of a Black blues singer whom he revered and who had died about 30 years prior. And he held the belief that Black people and white people ought to be segregated—at least enough to drunkenly rant about it on stage one night.

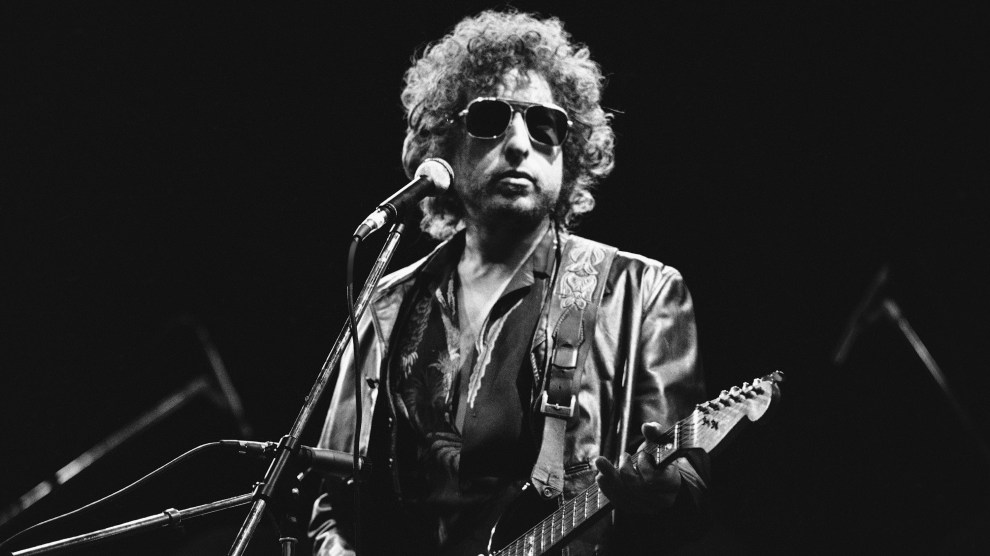

These two facts cannot be disconnected. I listened to Robert Johnson’s recordings for the first time earlier this year. I found them to be a revelation. In them, I heard the seed of much of the music I’d always known: Bob Dylan, Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones (whom I naively assumed had written “Love in Vain”), and, of course, Eric Clapton. Greil Marcus summarizes this sense of discovery in his 1975 book Mystery Train:

After hearing Johnson’s music for the first time—listening to that blasted and somehow friendly voice, the shivery guitar, hearing a score of lines that fit as easily and memorably into each day as Dylan’s had—I could listen to nothing else for months. Johnson’s music changed the way the world looked to me.

Appreciating Clapton’s art requires a certain ignorance of its origins. Clapton’s version of “I Shot the Sheriff,” for example, found more commercial success than Bob Marley’s original. But the lines “Sheriff John Brown always hated me / For what, I don’t know” undeniably carry less weight coming from a white man’s mouth.

Clapton recorded an entire studio album of Johnson’s songs, but, in the world of classic rock radio stations, Johnson is less an artist to be loved and enjoyed than a secret. I think that my ignorance about one of Clapton’s greatest influences reflects a broader cultural willingness to forget racism in favor of loving the music. But in pasting over the complexity, you lose out on the actual history.

Saturday is the 110th anniversary of Johnson’s birth. Listen to his “Cross Road Blues” here.