Luis Calderon AGE 22; Tank operator in the Army's 4th Infantry Division. Injured May 5, 2003, while destroying a mural of Saddam Hussein in Tikrit. Nina Berman/Redux

It’s hard to say just when the word “hero” went bankrupt. But in the aftermath of 9/11, America became, to its own mind, a nation of heroes. We spread the word around like butter on toast. It has become cultural pabulum, a national panacea, a psychological commonplace. Children are now encouraged by well-meaning adults to grow up to become their own heroes, as if that wouldn’t make them insufferable. And yet in a nation that is sick with celebrity, the word “hero” works in strange ways. We fear the elitism of the word, and so we democratize it, bestowing it everywhere, without really understanding what we’re doing. In the past few years, our overuse of the word has trivialized the notion of duty and diminished the idea of professionalism. We say the word “hero” so much that we must be very afraid, as if a world full of heroes felt safer or at least more interesting. Somehow our lives suddenly seem to require heroism to sustain them. It’s the password in an insecure world, the mantra we use against the dullness of ordinary life.

The men in these photographs are soldiers who were wounded in Iraq. Two of them were wounded in firefights. One was delivering ice. Another walked off into the desert on a bathroom break and stepped on a mine. One was wounded while blowing up a munitions dump. Two of the soldiers who look the least damaged are blind, far more damaged than the camera can record. Whatever they may feel about their condition now, these men tend to sum up our involvement in Iraq in simple, blunt phrases. Like this, from a double amputee: “The reasons for going to war were bogus, but we were right to go in there. Saddam was a bad guy.”

No one has the right to say that these men are not heroes. But I also suspect that few people understand the contemporary hollowness of that word better than they do. Private Jessica Lynch is only the most recent in a long line of soldiers throughout history to dismiss the word. To a soldier coming home from war, the word “hero” looks surprisingly like a gesture of incomprehension, especially in our time when the word is on everyone’s lips. It measures the appalling gap between civilians and soldiers, the inexplicable difference between peace and war.

Photos and Interviews by Nina Berman/Redux

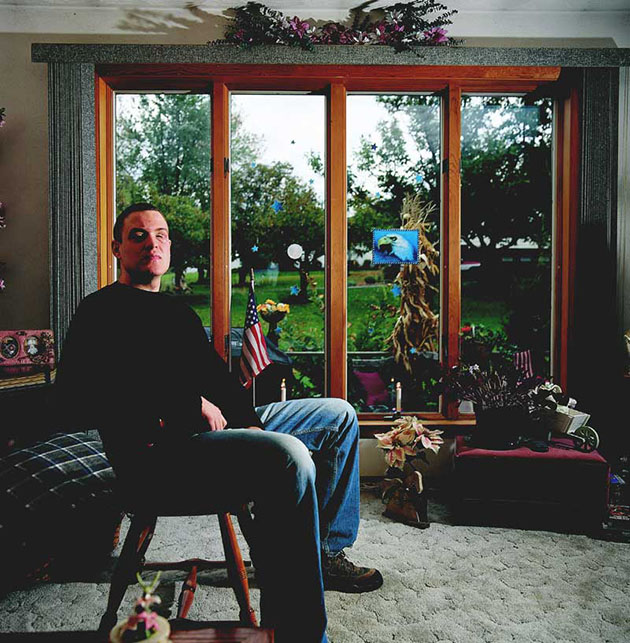

Tristan Wyatt AGE 21; FRANKTOWN, COLORADO

Machine gunner in the Army’s 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment. Lost his leg on August 25, 2003, during a firefight near Fallujah.

I was in the back of an armored personnel carrier. We got hit by a rocket-propelled grenade. It was a shitty day, to say the least. I just kept shooting. I thought I was dead anyway. I’ve had to relearn everything from standing up to walking. I’d been snowboarding for close to eight years before I got hit, and I’m just hoping to be able to do it again. I want to go back to the military. I want my old job back. I was infantry. We blew things up. I felt like my heart was in the right place over there.

Sam Ross AGE 21; DUNBAR TOWNSHIP, PENNSYLVANIA

Paratrooper and combat engineer in the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division. Injured May 18, 2003, in Baghdad, when a bomb blew up during a munitions-disposal operation.

I lost my left leg, just below the knee. Lost my eyesight, which it’s still unsettled about whether it will come back or not. I have shrapnel in pretty much every part of my body. Got my finger blown off—it don’t work right. I had a hole blown through my right leg—had three skin grafts to try and repair it. It’s not too bad now. It hurts a lot, that’s about it. You know, not really anything major. Just little things. I have a piece of shrapnel in my neck that came up through my vest and went into my throat and it’s sitting behind my trachea, and when I swallow, it kind of feels like I have a pill in my throat. I never had a health problem my entire life. Now I’m going to be seeing doctors every couple of months for the rest of my life. I just went and got fitted for my hearing aide. I’ve had 15 surgeries and at last 5 more to go. I ask myself that all the time, Why didn’t I die because in a sense. You know, I think I should have. It was the best experience of my life. Twenty-one years old and I’ve seen a couple of countries. I’ve been pretty much everywhere and done everything. I’ve jumped out of airplanes, I got to play with mines, got to see how the Army works. I got to interact with people of another culture, people who live their lives 100 percent different than the way we live here. That’s something that one in a million people will ever get to see in their lifetime—another culture. After high school I was kind of like undecided on what I wanted to do in life. And I went to Texas for a while and stayed with one of my aunts who lives down there. I got a job but got bored with the life. I worked in a machine shop. $27 an hour, more than I make now. It was a good job, right out of high school. Everybody’s dream job, but it was kind of boring just standing there all day. I always thought I could do a little bit more than just stand there. So I came back home and joined the army. I want to go into politics. Run for office, maybe.

Erick Castro AGE 24; SANTA ANA, CALIFORNIA

Combat engineer in the Army’s 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment. Lost a leg on August 25, 2003, during a firefight near Fallujah.

I was born in Mexico—I came here when I was one. I just became a U.S. citizen in December. There was this two-star general at the hospital that asked me, “Hey, are you a citizen?” That same day, I saw Senator Kennedy, and I decided to apply. The director of the INS performed the ceremony in Senator Kennedy’s office. I met a guy in the Army who thought all Mexicans were illegal. And he was like, “How’d you join the Army if you’re illegal?” So I explained to him exactly what it meant to be illegal. Before, I was just a soldier from another country. Now I have actually done something for my country. Now I have to wear a prosthetic. Or if I don’t want to wear it, I hop around on crutches. My life has changed a lot… a big distance from where it was before. But I’m actually glad I did it, that I served. I don’t regret the injuries, not at all. It’s just what happens in those circumstances. I got a Purple Heart from the President in Washington. He just came down and handed it to me. I don’t regret joining. If I could do it again, I would. I wanted to do something different. Now, I’m going to go back to school. The VA will pay for tuition. I’ll go to school for 2 or 3 years. I think what I’ll do is mechanical engineering. Then find a job in that.

Alex Presman AGE 26; SHEEPSHEAD BAY, NEW YORK

Heavy-vehicle operator in the Marines’ 6th Communication Battalion. Injured July 15, 2003, outside Baghdad when he stepped on a land mine.

I was born in Russia. We came in ’94. I think a man has to go through the military. My father was in the military. I wanted to go to school, and I just thought it was the right thing for me to do. I volunteered to go. I could have gotten out, because my reserve contract was over. I volunteered basically, because a couple of my good friends were going and being in the military is what’s it’s all about. It’s about doing something. Being in the military action. I just wanted to be a part of it. We stopped for a break and some people went to use the bathroom, four guys in front of me. I was following them, and boom, it took off my foot. It threw me up, and I just fell down. At first, I was a little shocked. I didn’t understand what happened. They medevaced me out, took me to Bethesda Naval Hospital, and they told me it had to be amputated. Nobody can prepare himself for that. But you know, it could have been worse. It’s just pride. The brotherhood. The way of life. Being in the military, and being one of the few, the proud. Once a Marine, always a Marine.

Jeremy Feldbusch AGE 24; DERRY TOWNSHIP, PENNSYLVANIA

Mortar gunman in the Army’s 3rd Battalion, 75th Regiment. Injured April 3, 2003, while defending the Haditha Dam; suffered brain damage and lost his eyesight.

I graduated from the University of Pittsburgh. I was a biology major. At one point in my life, I wanted to be a doctor. Even while I was going through college, I thought about going into the military. And when I was done, I thought, “You know what, I would like to do that.” I knew about the Middle East as much as I needed to. But it didn’t make a difference. I wasn’t fighting a political war with them anyway. That was already taken care of. That’s about it. I don’t have any regrets. I had some fun over there. I don’t want to talk about the military anymore.

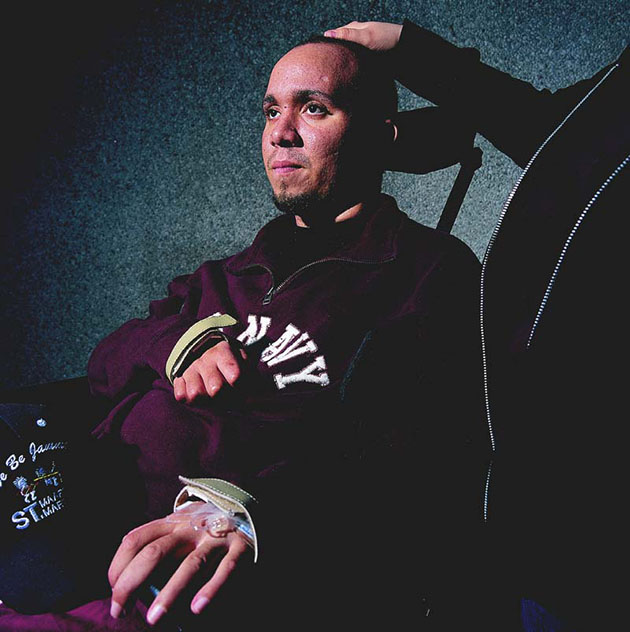

Luis Calderon AGE 22; MIAMI, FLORIDA

Tank operator in the Army’s 4th Infantry Division. Injured May 5, 2003, while destroying a mural of Saddam Hussein in Tikrit.

The wall just crashed on me. Crushed my head, broke my neck. I felt separated, like in relaxing mode, but really I was still driving the tank. I couldn’t feel my hands on the wheel. I felt nothing. My sergeant was telling me to stop on the radio, but I couldn’t speak loud because my voice just went away, I was whispering, a very slight whisper. Another tank got the wall from ahead and took it out, and we waited until the medics came. They took me to the support camp, and that’s where the doctors determined I had a broken neck and a spine injury. My spinal cord is C3-C4—quadriplegic. From my neckline down I cannot feel anything. I’m just happy I took the wall down. I did my job. If I had the chance to, I would go back now. I wanted to be a diesel mechanic. I was going to make a career in the Army, do my 20 years. I got an Army Commendation Medal—not a Purple Heart. I’m disappointed. It would make me more confident that I really did something. There’s another story I can tell in the future to my kids. I still think I’m active. I’m 22 years old. You don’t see a lot of veterans at 22 years old. I would like to talk to soldiers. Do volunteer work. Just talk to soldiers. But for the moment, right now, I just want to heal.

Alan Jermaine Lewis AGE 23; MILWAUKEE, WISCONSIN

Machine gunner in the Army’s 3rd Infantry Division. Wounded July 16, 2003, in Baghdad, when the Humvee he was driving hit a land mine.

I remember every detail about my legs. Every detail from the scars to the ingrown toenails to the birthmarks to the burn marks. I made it a habit, even before I joined the military, to cherish every part of my body, because I would always look at it like, “What if this finger was gone, would I be able to function without it?” I don’t know why. Maybe it was God’s way of preparing me for what was going to happen. I’ve always thought about death—just growing up in Chicago and living out here in this world. I had a friend when I was six years old, his name was Charles. He was shot in the head—I think it was a stray bullet. My oldest sister was killed by a stray bullet when I was just a couple of months old, and my father was killed when I was seven. He was being robbed. So death has always been around. I’m actually glad that I did the military the way I did—that I lived in the world for a couple of years—because I never would have known what it would be like to live on my own and be able to have parties at my house and own a car and do things like that. I’ve always wanted to go into education and become a teacher but they just don’t make enough to survive off of. So I figure with my disability now, and the money I’ll get from the government, I can use that plus the money I’ll get from being a teacher and live comfortably. So I want to go to college and study education. I’ve been dealing with the military since I was a sophomore in high school. They came to the school like six times a year. They had a recruiting station like a block from our high school. It was just right there. I could have gotten any job I wanted in the military. But my idea of a solider is hard-charging, the guy with the guns. So I didn’t want to go into the military and do anything else besides that — I signed up for infantry. The reasons for going to war were bogus but we were right to go in there. Saddam was a bad guy. But the Purple Heart was one thing I never wanted. The Secretary of the Army gave it to me.