The high price of prescription drugs has put — and kept — U.S. pharmaceutical companies in the news recently, but Dr. Marcia Angell argues that problems with the industry run even deeper. In her new book, The Truth About Drug Companies: How They Deceive Us and What to Do About It (reviewed in the current issue of Mother Jones), the former editor of the New England Journal of Medicine contends that the industry has become a marketing machine that produces few innovative drugs and is dependent on monopoly rights and public-sponsored research.

Angell disputes the industry’s reputation as an “engine of innovation,” arguing that the top U.S. drug makers spend 2.5 times as much on marketing and administration as they do on research. At least a third of the drugs marketed by industry leaders were discovered by universities or small biotech companies, writes Angell, but they’re sold to the public at inflated prices. She cites Taxol, the cancer drug discovered by the National Institutes of Health, but sold by Bristol-Myers Squibb for $20,000 a year, reportedly 20 times the manufacturing cost. The company agreed to pay the NIH only 0.5 percent in royalties for the drug.

The majority of the new products the industry puts out, says Angell, are “me-too” drugs, which are almost identical to current treatments but “no better than drugs already on the market to treat the same condition.” Around 75 percent of new drugs approved by the FDA are me-too drugs. They can be less effective than current drugs, but as long as they’re more effective than a placebo, they can get the regulatory green light.

Finally, Angell attacks major pharmaceutical industry — whose top ten companies make more in profits than the rest of the Fortune 500 combined — for using “free market” rhetoric while opposing competition at all costs. She discusses Prilosec maker Astra-Zeneca, which filed multiple lawsuits against generic drug makers to prevent them from entering the market when the company’s exclusive marketing rights expired. The company “obtained a patent on the idea of combining Prilosec with antibiotics, then argued that a generic drug would infringe on that patent because doctors might prescribe it with an antibiotic.”

Angell, who is a doctor and a lecturer at Harvard Medical School, wants to see the industry reformed. She recently sat down with MotherJones.com to talk about how to “ensure that we have access to good drugs at reasonable prices and that the reality of this industry is finally brought into line with its rhetoric.”

MotherJones.com: Pharmaceutical companies say higher prices are necessary to pay for heavy R&D investment.

Marcia Angell:These companies are justifying extremely high prices by saying they need this money to cover their high R&D costs, and they’re very innovative, and that we should be willing to spend the money in return for the innovation. In the book, I question those premises. I say that, yes, they spend a lot on R&D, but still they make more in profits, and they spend two to two-and-a-half times as much on what they call “marketing and administration.” If you want to argue that they need the high prices to cover R&D, it would make more sense to argue that they need the high prices even more to cover their marketing costs. I just want to put that in perspective. Also, their profits are enormously high. Until last year, [they were] the number one industry in the U.S. in terms of profits. In 2002, the top 10 American [pharmaceutical] companies in the Fortune 500 made 17 percent of their sales in profits, whereas they spent only 14 percent on R&D. The median for the other Fortune 500 companies was between 3 percent of sales. So, you can’t make an argument that they’re just eking out a living, just managing to cover their R&D costs.

MJ.com: Your numbers for how much companies spend to bring drugs to market are very different from the industry’s. How come?

MA: The industry arrives at that $802 million [per drug] figure by looking at a tiny handful of the most costly drugs. Those are drugs that were developed entirely in-house, and that are new molecular entities. That’s a very tiny handful of the drugs that come to market each year. They’re the most expensive drugs. Second, even for those drugs, they come up with a figure of $403 million per highly selected drug. They then double that to $802 million simply by adding in what they call the “opportunity costs” — what they could have made if they’d spent the same money on investments. Third, the figure is inflated by not including the tax deductions and tax credits. They get very large tax deductions and credits. So the figure is highly inflated. That gets buried in the reporting of it. When you hear the figure, you hear it given with the implication that for any random new drug, that’s what it costs to develop it. And that’s just simply not so.

MJ.com: In your book, you charge that even some of what the industry calls R&D is actually marketing. Can you elaborate on that?

MA: Well, no one knows for sure what goes into the R&D budget, because the companies aren’t telling. It’s been estimated that about a quarter of it is spent on Phase IV clinical trials, many of which are just excuses to pay doctors to prescribe the drug. They don’t yield any real scientific information. But no one knows for sure.

MJ.com: So should the pharmaceutical industry be making its books public?

MA: Yes, because it’s an industry that is so dependent on the public for special favors. This industry, despite its free-market rhetoric, is on welfare big-time. It lives on taxpayer-funded research to a very great extent, and it lives on government-granted monopoly rights in the form of patents and FDA-conferred exclusivity. An industry that is so beholden to the public has some obligation in return. That includes opening their books. We ought to know more about their business. We ought to know whether the claims they make can really be justified.

MJ.com:Why should the industry have to open its books — or be asked to charge less for its products, for that matter — when other industries aren’t held to those standards?

MA: The public is absolutely dependent on this industry for drugs that people need to take for their health and even their lives. So, I think there are some special obligations.

MJ.com: In the past you’ve written that “there can be no better example of something that does not belong in the market [than prescription drugs],” but you don’t address that in the current book. Do you still think so?

MA: I don’t think I’ve ever said that they should come off the market, but there need to be reforms that accomplish several things. [Pharmaceutical companies] have too much influence over the education of physicians in this country. They have too much control over the evaluation of their own products, and that’s a conflict of interest. I think the industry needs to be regulated, but I’ve never suggested taking it out of the market altogether. It’s now a funny mix of free enterprise and welfare. On the one hand, it is free to choose to make whatever drugs it wants to make. If it wants to make one more me-too drug, it’s free to do that instead of making an antibiotic that may really be needed. It’s free to charge whatever the market will bear in this country. And at the same time, it claims all sorts of special favors. It claims that Americans should not be allowed to purchase drugs in any other country. It claims the right to license taxpayer-funded research. It not only claims the right to very long patents, but extends them in all kinds of quite dubious ways. Now, this is hardly free enterprise.

MJ.com: In terms of licensing drugs from publicly-funded institutions, how much do companies generally pay? Is it relative to how much they charge?

MA: I don’t know. I know in the case of Taxol, it was very little. In general, when companies license a drug from universities, it’s not all that much compared with the profits. They’re licensing now from small biotechs as well. The industry likes to portray itself as the engine of innovation, but in fact its major products are me-too drugs—minor variations of drugs already on the market. For example, we have six cholesterol-lowering statins on the market right now; we have five SSRI anti-depressants; we have nine ACE inhibitors to treat high blood pressure. If you look at the top-selling drugs on the market right now, most of them are me-too drugs, and the original of these drugs came on the market back in the ‘80s, or even earlier. The companies have been stringing out variations on the themes ever since. The original drugs were usually based on government university research.

MJ.com: Regarding me-too drugs, can’t one make the argument that there should be as many different variations of a drug as possible on the market? Shouldn’t the market decide?

MA: We have an FDA because what drugs to sell isn’t something for the markets alone to decide. It’s also a technical decision that requires scientific evidence. The companies don’t want to provide that evidence. They don’t test their me-too drugs against other me-too drugs at comparable doses for the same conditions. The companies also make the case that there need to be several me-too drugs on the market because if one doesn’t work, maybe another one will. But until they test that, it’s just an assertion. They don’t test their me-too drugs in people who have not done well with an earlier drug of the same class. They have to do that in order to prove that assertion. I suspect that in most cases, a second drug will not work any better, since me-too drugs are so similar, but no one can know until it’s tested.

MJ.com: Speaking of the FDA, you characterize the agency as one that facilitates new drugs, rather than regulating them. To what degree is the agency controlled by the industry it’s supposed to regulate?

MA: Too much. The FDA now gets “user fees” from drug companies—about a half a million dollars for any drug that the FDA reviews. Those user fees are small for the companies, but it’s a substantial part of the FDA budget. In fact, it’s more than half [the budget for] the Center for Disease Evaluation and Research, which is responsible for approving new drugs. In return, the FDA is supposed to review drugs faster.

MJ.com: So you would propose getting rid of those user fees?

MA: Absolutely. I think that the FDA should be funded adequately by taxpayers, and it should see taxpayers as the “users.” It should not be funded by the industry it’s supposed to be regulating.

MJ.com: One of the changes you propose in this book is that the NIH — and not drug companies — be responsible for clinical research. But you propose that drug companies help pay the NIH to do this. Couldn’t this lead to a similar problem?

MA: No, because instead of paying user fees by drug, companies would be levied a very small percentage of their revenues. It wouldn’t be tied to research on any particular drug. This would be only for clinical trials, not the early development stage. The NIH would put out contracts to universities and medical centers to actually design and carry out the clinical trials, but the NIH would have oversight.

MJ.com: FDA commissioner Lester Crawford recently warned against buying drugs from Canada, citing potential terrorist threat if drugs are tampered with. Is there a valid concern there?

MA: There’s no reason to think that drugs that are imported from Canada are any more likely to be unsafe than drugs that one gets right here. In fact, the cases of counterfeiting that I know of have all occurred in this country. So there’s some reason to think that maybe it’s safer to get your drugs from Canada [laughs]. The drugs that an American would purchase from Canada are going to be the drugs that they ordinarily pay much more for here—that is, FDA-approved drugs. They’re not going to be buying just something in a bottle; they’re going to be buying FDA-approved drugs that were shipped to Canada from European and American companies which have manufacturing plants all over the world. We have to remember that drugs are crossing borders all the time. Pfizer, for example, said on its website last year that it had 60 manufacturing plants in 32 countries. That right there constitutes a lot of borders. There’s nothing about the Canadian border that’s going to render these drugs poison. It’s a scare tactic. What the industry does not want people to realize is the great price disparities between the United States and every other advanced country.

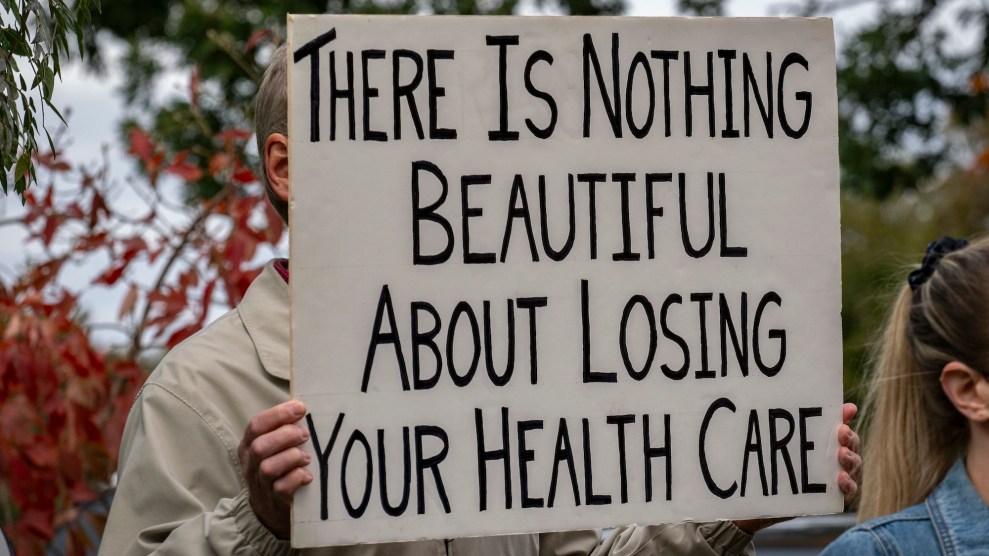

MJ.com: In the past, you’ve criticized the U.S. health care system, saying that “if we had set out to design the worst system we could imagine, we couldn’t have imagined one as bad as this.” Do you still believe that?

MA: The market-based pharmaceutical industry is one problem in the larger problem of a market-based health care system. We spend twice as much per person on health care as the average of all the other advanced countries, and that gap is growing. Yet, we get less for our money. We have over 40 million people with no insurance at all. Most of the rest of us are under-insured. The usual indices of health, like life expectancy and infant mortality, are toward the bottom in the U.S. compared with other advanced countries. So, something’s wrong, and it’s the system. A market-based system distributes health care as a commodity according to the ability to pay, instead of as a social service distributed according to need. Yet, there’s an inverse relationship between one’s ability to pay for health care and one’s medical needs. The situation gets crazier when you allow competing, investor-owned insurance companies to insure Americans, because they have learned that the best way to compete is to keep costs down by skimping on health services. We have the only health care system on the world that’s based on dodging sick people. [Insurers] do everything they can to avoid covering people at high risk of getting ill, and when they do get ill, [companies] fight paying for it. They exclude certain expensive conditions as much as possible. They pass those costs back to the patient or another insurer. And that takes a lot of paperwork, and a lot of overhead.

MJ.com: In the book, you mention that every other developed nation regulates prescription drug prices—

MA: Yes, but they have different ways of doing it. If you look at Canada, it’s a very mild form of regulation, really. They have a national board, and when a me-too drug comes on the market, they say it can’t be priced any higher than the highest-priced drug for that condition already on the market. Nor can it be priced any higher than the median in seven advanced countries, and these countries include the U.S. Then they say the prices cannot rise any faster than the inflation rate. So, that’s not too onerous. Drug companies make profits in Canada.

MJ.com: Is that an example of a system you’d like to see in the U.S.?

MA: Yes. Importing drugs from Canada is not a very sensible solution, because Canada can’t possibly supply the U.S., and the drug companies are now retaliating against Canada and squeezing their supplies. So, importation is not a long-term solution. It’s just a symptom of the real problem of price-gouging in this country. We should be looking at the Canadian system, and maybe import that rather than importing the drugs.

MJ.com: Realistically, do you think a system of price controls like that could ever be instituted in the U.S.?

MA: Well, something’s going to have to happen, because there’s no one around any longer who can afford the drug company prices. Not only are individuals having problems, but states are having problems. They feel these prices through the Medicaid system. The federal government is going to find that this fairly open-ended Medicare drug benefit is going to be completely outpaced by the rising prices.

MJ.com: If pharmaceutical manufacturers were forced to lower prices, couldn’t it backfire if they cut back on research as a result, rather than marketing?

MA: Well, they might choose to do that, but they wouldn’t have to. They could cut their marketing instead, or they could cut into their profits. Their R&D very often comes from the NIH or other publicly sponsored research. Most of their R&D expenditures go for clinical testing after the creative work is already done. This is true for the most innovative drugs, as well as for cancer and HIV/AIDS drugs.

MJ.com: You say that there’s “palpable” discontent among seniors and others about drug prices. Do you see this as having an effect on the problems you described in the book?

MA: I think that there are political effects, and I think that’s what you’re seeing right now with the importation issue. Congress has passed a law saying that you can import drugs from Canada, but that the administration must certify that it not add any risks. Both the Clinton and Bush administrations have refused to do that. It’s giving Congress an opportunity to play both sides of the street.

MJ.com: Given that Congress is torn between seniors and the pharmaceutical lobby, do you think change will ever occur?

MA: I think that the public doesn’t seem to be buying the argument that drugs from Canada are dangerous. If it comes down to choosing between the money that drug companies provide and the votes that citizens provide, I think members of Congress are going to go with votes. That’s what I hope will happen.

MJ.com: In the conclusion of the book, you stress that citizens should grill their doctors regarding drugs they’re prescribing. Why do you recommend that type of action most heavily?

MA: The other reforms will take time, but in the meantime, doctors are too willing to provide drugs for very minor conditions. Those drugs are too often the very most expensive, heavily advertised, me-too drugs. I think that patients have to get a little savvier about that. Instead of just grabbing that sample and thinking they’ve gotten something for free, they ought to think about what it means. Nearly every drug has side effects. I do think that we are an overmedicated society.