Illustration: Maurice Vellekoop

At a strip mall clogged with Ferraris and fashion boutiques, Beretta Gallery salesman Chris Cope shows me a framed photo of one of his best clients, an oilman posing next to a bounty of elephant tusks. In addition to selling massive safari rifles, this high-end Italian weapons emporium in the Dallas suburb of Highland Park supplies $130,000 Imperiale Montecarlo shotguns as well as petite .22s and chic, lockable handbags to conceal them. All told, it sells more firearms than any other Beretta outlet in the world. Last year, the store presented George W. Bush with a $250,000 shotgun engraved with the presidential seal, a picture of his Scotty dog, and “43” on the lever. The gun, which required more than a year to assemble, was a thank-you from Mr. Beretta for a military order of a half-million pistols.

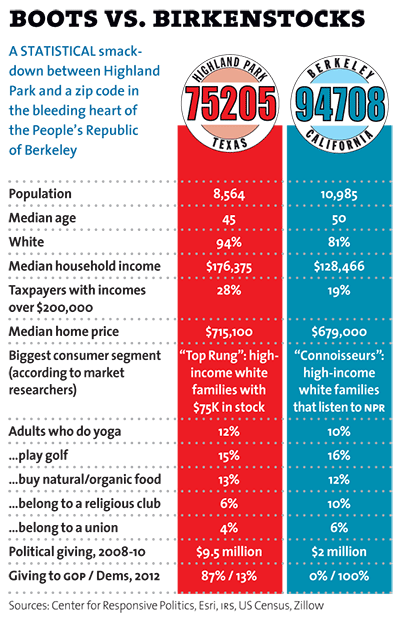

It’s fair to call 75205, the zip code for most of Highland Park, the most enthusiastically Republican enclave in the country. Among the two-dozen zip codes that donated the most money to candidates and political parties last year, 75205 gave the highest share—77 percent—to Republicans, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. It also gave Republicans more hard cash, $2.4 million, than all but four other zips nationwide. Affluent, insular, and intensely sure of itself, Highland Park is the red-state counterpart of, say, Berkeley. It’s a place where, one native son half-jokes, friends might ask one another, “Do you want to come over for barbecue after we go vote for Mitt Romney?” People in the surrounding city of Dallas, where I grew up, call it the Bubble.

“We don’t need the government to do things for us—that’s why the town is very, very independent,” says Ray Washburne, a co-owner of the Highland Park Village mall and a native “Parkie.” In 2004, Washburne and George Seay III (pronounced “see”), a grandson of Texas’ first 20th-century Republican governor, cofounded Legacy, a group of 200 families that “have been successful in their careers and want to be involved in the political process.” The group hosts aspiring GOP presidential candidates at a yearly summer retreat in Colorado, where they “network with other people who have been trying to push along the conservative, free-enterprise cause.” Washburne befriended former Minnesota Gov. Tim Pawlenty at an event in 2008 and later joined his short-lived presidential campaign.

Other big Republican donors here include the Hunt oil family, the children of Ross Perot, and venture capital heiress Dianne Cash, who bought Dick Cheney’s Highland Park residence in 2000. Billionaire Robert Rowling, the owner of the Gold’s Gym and Omni Hotel chains, gave, along with his holding company, $5 million to Karl Rove’s super-PAC last year. Real estate mogul Harlan Crow often hosts party fundraisers at his $24 million spread. He’s presented numerous gifts to Clarence Thomas, including funding for a library project dedicated to the Supreme Court justice, a bust of Abe Lincoln, and, according to Politico, $500,000 in seed money for Thomas’ wife, Virginia, to start a tea party group.

Other big Republican donors here include the Hunt oil family, the children of Ross Perot, and venture capital heiress Dianne Cash, who bought Dick Cheney’s Highland Park residence in 2000. Billionaire Robert Rowling, the owner of the Gold’s Gym and Omni Hotel chains, gave, along with his holding company, $5 million to Karl Rove’s super-PAC last year. Real estate mogul Harlan Crow often hosts party fundraisers at his $24 million spread. He’s presented numerous gifts to Clarence Thomas, including funding for a library project dedicated to the Supreme Court justice, a bust of Abe Lincoln, and, according to Politico, $500,000 in seed money for Thomas’ wife, Virginia, to start a tea party group.

It’s no secret why Highland Park attracts so many rich conservatives. It has a prime location near Dallas’ financial center and one of the lowest property tax rates in a state with no income tax. Yet it has one of the nation’s best school systems and an average emergency response time of 2.5 minutes. “Highland Park is safe,” says Mary Bosworth, a local GOP precinct chair. “You call the fire department and they’ll be there in three minutes, versus ‘Are you dead yet?’ in Dallas.”

Wilbur David Cook, the urban planner who designed Beverly Hills, drew up the plan for Highland Park a few years before it was incorporated in 1913. One of the community’s first (if factually dubious) slogans, “It’s 10 degrees cooler in Highland Park,” reflected its attractiveness to the elite, as did its restrictions prohibiting property sales to minorities. A friend who is a descendant of one of Highland Park’s founding families was discussing this history over lunch at Washburne’s Mi Cocina restaurant when a black acquaintance, a successful loan broker, stopped by our table. Answering before I could ask, my friend said, “He does not live in Highland Park.”

No African Americans owned homes there until 2003, when mortgage officer Karen Watson purchased a house on ritzy Beverly Drive. “Guess who’s coming to dinner—and staying for awhile?” wrote the local paper, Park Cities People. According to the 2010 census, Highland Park is 94.4 percent white (PDF). In 2005, Highland Park High School students celebrating “thug day” and “fiesta day” came to class dressed in Afro wigs and traditional Mexican dresses stuffed with pillows. (The previous year, some had celebrated “trailer trash day” by dressing as their teachers.) Lambasted as recently as last year for not admitting African Americans, Highland Park’s 117-year-old Dallas Country Club revealed, after repeated calls, that it does in fact have black members but wouldn’t say how many or when they joined. A Parkie friend whose family belongs to the club told me he has never seen a black member.

Over the years, the Highland Park police has been repeatedly accused of racial profiling. A 2007 report by the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition (PDF) found that the town’s officers searched black drivers four times more often than whites. The cops are also known for stopping people who, as a former officer testified in a civil rights suit against the town, “did not blend in.” Daniel Kanter, a local Unitarian minister, believes he was pulled over because he drives a battered Toyota Corolla. “Beyond racial,” he says, “it’s profiling by the make and model of your car.”

Defenders of the Bubble say it’s unfair to brand it as exclusionary, self-absorbed, or materialistic. A friend cites the story of Charles E. Seay, a.k.a. “Big Charlie,” a self-made insurance millionaire and George Seay III’s great-uncle. On a 1989 trip to Acapulco, Seay’s van tumbled off a cliff but was caught by a lone madrona tree. Seay concluded that God had put him on earth for a purpose. By the time he died in 2009, he’d given away tens of millions of dollars to local hospitals, museums, and the YMCA. “Because he did, other people did too,” my friend said. Today, many big Highland Park social events are charity balls.

Of course, the Parkies would much rather comfort the afflicted than afflict the comfortable. In 2006, Garrison Keillor, host of the public radio program A Prairie Home Companion, visited the Highland Park United Methodist Church. “Within 10 minutes [I] was told by three people that this was the Bushes’ church and that it would be better if I didn’t talk about politics,” Keillor later wrote in an indignant op-ed. “I was there on a book tour for Homegrown Democrat, but they thought it better if I didn’t mention it.”

As a senior at Highland Park High in the mid-’90s, Butler Looney hung out with the only black girl in class and grew his curly hair slightly longer than average. He thinks that’s why his class voted him “Most Liberal.” (He later designed the seal for the George W. Bush Presidential Library.) “People in Berkeley are kind of the same,” says Looney, who, like me, eventually moved from Texas to the San Francisco Bay Area. “It’s like, ‘I can’t believe that you would associate with those other kinds.'” Yet he’s not offended by liberal friends who diss his hometown or Parkies who can’t comprehend why he left. “It’s not out of malice. They just have no concept of the other side.”