A rape victim tells her story at an Anonymous rally in Steubenville, Ohio.Courtesy MC

Two years ago, Rehtaeh Parsons told her mother that four boys had gang-raped her while she was drunk on vodka at a house party. A photo of the 15-year-old throwing up during the alleged assault blew up on social media, and soon Parsons’ classmates and peers in Halifax, Nova Scotia, were texting her invitations to have sex with them and calling her a “stupid slut.”

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police eventually abandoned her rape case, claiming a lack of evidence, and Parsons, who had been a straight-A student, dropped out of school and struggled with depression. Then, last month, she hanged herself in a bathroom.

Instances of teenage girls being sexually assaulted and cyberbullied are so common that they rarely make the news. In the Parsons case, people started paying attention not because the episode was particularly egregious (it was), but because it sparked a new vigilante campaign by Anonymous, the global hacktivist collective.

“I think that you can say without a doubt that it was a rape,” says a spokesman for the small group of Anons who coalesced around the Twitter hashtag #OpJustice4Rehtaeh last month. It only took the group about two hours, he says, to track down the photo of the alleged rape and identify the boys involved. Now the group is threatening to name them publicly if the Canadian authorities fail to bring them to justice.

Though Anonymous is best known for targeting corporate websites, pwning religious extremists, and championing Occupy Wall Street, members of the loose-knit group have more recently branched out to go after rapists. In Steubenville, Ohio, last year, the group was instrumental in highlighting the alleged complicity of members of a local high school football team in the rape of 16-year-old girl by two of their teammates and turning it into a national story.

Targeting rapists and their enablers isn’t necessarily something one might expect from Anonymous, which springs from an online geek culture long on the Y chromosome. Just a few years ago, the group existed almost entirely on 4Chan, a no-holds-barred internet chat room where rape would be more likely to come up in a punch line—if not an insult involving someone’s mother. Even now, only about a third of the followers of the largest Anonymous Twitter account, Your Anon News, are women, according to someone who helps run the account.

The demographic is “guys sitting around playing Worlds of Warcraft and drinking beers” or “out on the streets where there’s riots and kettles,” says MC (@Master_Of_Ceremonies), a spokesman for the Anonymous effort in Steubenville. “It’s just kind of more of a guy-mentality thing.”

Or it was, at least, until the group’s anti-rape ops kicked in.

Until now, the story of how Anonymous got involved in the Steubenville case has never been told in full. The group’s interest was sparked by Michelle McKee, a 50-year-old* victim of childhood sexual abuse who says she more recently was nearly driven to suicide by a vicious internet troll.

McKee, who lives in Washington state, is friends with Alexandria Goddard, an Ohio blogger whose reporting on the case drew a defamation lawsuit by the family of Steubenville High School football player Cody Saltsman. (The case was ultimately dismissed.)

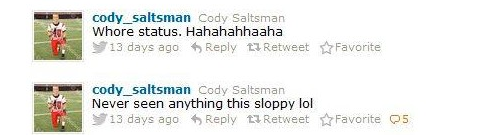

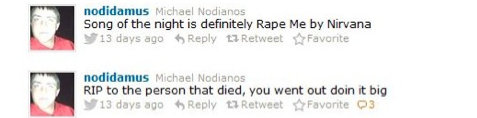

By then, police had arrested and charged two of Saltsman’s teammates with raping a passed-out girl at a drunken house party. Social media was awash with evidence that other team members had not simply failed to stop the assault, they had callously belittled the victim. Saltsman, for one, allegedly posted the Instagram photo at right showing the accused rapists lugging the unconscious girl by her hands and feet. He tweeted:

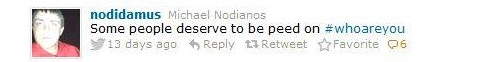

Michael Nodianos, another reveler who’d heard about the incident, chimed in:

Disgusted by the rape and the lack of outcry in its aftermath, McKee spent weeks calling and emailing national journalists, urging them to write about the assault and the lawsuit against her blogger friend, who had hammered away at the football team and the community for their silence.

After striking out, McKee eventually stumbled upon #OpAntiBully, an Anonymous subgroup that goes after cyberbullies. Members of the operation had recently orchestrated a dramatic takedown of a clan of high school Twitter trolls who’d urged a suicidal 15-year-old to cut herself and drink bleach. McKee was deeply impressed. “People from Anonymous came and kicked their ass,” she recalls, speaking out about her involvement for the first time. “And I’m thinking, this is what [the rape victim] needs.”

So McKee nervously reached out to the Anons on Twitter. “I thought they would either get involved or get pissed, and my online life is over,” she told me. But where she expected a bunch of impetuous hackers, she instead encountered people who were willing to listen and to trust her—especially after she shared her own stories of being bullied and abused.

On December 10, she became the first second person to blast out the now-famous Twitter hashtag #OpRollRedRoll, a reference to Steubenville High’s beloved Big Red football team and its fansite, RollRedRoll.com (Update: McKee says the first tweet of the hashtag was from @KYAnonymous but isn’t visible because his account is suspended):

To Cody Saltsman &all the #BigRedRapers, those behind cameras 2those in front & every1 in between youtube.com/watch?v=tpsSfq… #OpRollRedRoll

— Michelle McKee (@MichelleLMcKee) December 10, 2012

“Once it became an Anonymous op,” McKee says, “it was no longer in my control. It was kind of like being a baton runner and handing it off to the next person.”

About two weeks later, the Anonymous subgroup KnightSec hacked RollRedRoll.com. The hackers posted the incriminating tweets, Saltsman’s Instagram photo, and the names of 11 bystanders. “This is a warning shot,” said a video communiqué featuring a computer-generated voice and the group’s trademark Guy Fawkes figure. The video (watch below) warned that KnightSec would release the phone numbers and Social Security numbers of the entire football team unless “all accused parties come forward by New Year’s Day and issue a public apology to the girl and her family.”

In a town where being a starting varsity football player is tantamount to royalty, the hack and the threat didn’t win Anonymous many friends. Moreover, KnightSec had wrongly named one player who wasn’t at the party (it later retracted his name), adding to a perception that it was engaged in a witch hunt. When KnightSec called for an “Occupy Steubenville” rally on the courthouse steps in late December, the turnout wasn’t all that impressive, MC told me. But that would soon change.

*Correction: The original version of this article had McKee’s age wrong.

New Year’s Day came and went, and KnightSec—at the victim’s request, according to MC—refrained from publishing the players’ private information. But KnightSec had reached out quietly to witnesses, and on January 2, its members released a different kind of bombshell: a video of Steubenville High graduate and Ohio State University student Michael Nodianos at a party on the night of the rape, laughing hysterically as he joked repeatedly about the victim being “dead” and getting peed on. “They raped her harder than that cop [actually a pawnshop owner] raped Marcellus Wallace in Pulp Fiction,” he guffawed. “She is so raped right now,” he said at one point.

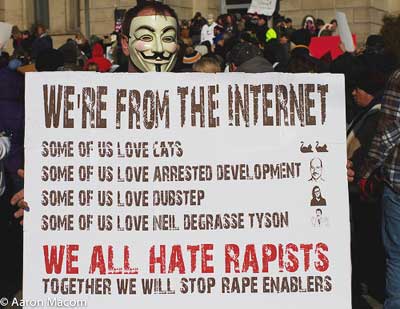

The video went viral, and the next Occupy Steubenville rally drew 2,000 people to the courthouse steps. Because MC brought the sound system, he ended up serving as the de facto master of ceremonies (which is how he ended up with his Twitter handle). As he played excerpts of the Nodianos video over the loudspeakers, he told me, people in the crowd grew so angry that he started to worry that they would riot.

When the Steubenville sheriff showed up, MC invited him up and grilled him about the case. In the end, he diffused the tension by giving the cop a hug. “I’m going to take this negative energy and turn it into a positive thing,” he remembers thinking. “You’ve got to let the crowd vent.”

And vent they did. For four hours, there was a catharsis of personal pain and grief that nobody in the small town could have imagined. Women who had been raped stood in front of the crowd, clad in Guy Fawkes masks, to share their stories. Some of them unmasked at the end of their testimonies as they burst into tears. Rapes at parties, date rapes, rapes by friends and relatives—their pent-up secrets came pouring out. “It turned into this women’s liberation movement, in a way,” MC recalls. “And it just changed everything. There was nothing anybody could do against us at that point because it was so real and so true.”

Here are a few excerpts, recorded through the sound system:

In the wake of the Nodianos video and subsequent rally, Anonymous was besieged by people wanting to join, many of them women. Yet the events also triggered cyberthreats against the sheriff and the implicated students. A mother of one football player ranted, during a Dr. Phil taping, that some of the kids were too terrified to go to school, and were sitting “in a corner…puking, peeing in their pants.”

In March, a judge sentenced Ma’lik Richmond and Trent Mays to a minimum of a year in a youth correctional facility for raping the girl, and Mays was given an additional year sentence for disseminating nude photos of a minor. The next month, #OPRollRedRoll held its ninth rally, this time outside the building where a grand jury was being assembled to look into who else may have known about the rape and not come forward. A week later, police executed search warrants on Steubenville High School and the offices of the Steubenville school board.

Like many of Anonymous’ actions, the anti-rape ops have been intimidating to their targets and fascinating to the press due in part to their unpredictability. One moment, they might come off like something organized by a mainstream group like Take Back the Night. The next, like a virtual lynch mob of impulsive twentysomethings.

“What kind of [self]-respect do you got, to go bang an unconscious chick? What, you couldn’t find one awake? Dude, she was out cold!” says MC, who works as a roadie for a sound production company.

Vigilante-style online activism “is still very much uncharted territory,” says Tim King, a visiting professor at the University of California-Berkeley who studies cyberbullying. “This power can be used for justice and doing what most people view as the right thing, but it can also very quickly turn into a witch trial. It really depends on who is wielding the power and how responsible and cautious they are with it.”

While the Steubenville operation inspired other Anons to launch #OPJustice4Rehteah, it also served as a cautionary tale. “One of the reasons I wanted to get involved to begin with was that I didn’t really like the way that the stuff in Steubenville was handled at all times,” says the Canadian op’s secretive spokesman and ringleader, whom I’ll call Fawkes. “I’m glad that it happened, but I’m not convinced that all of the people who were implicated were guilty. I wanted the chance to work on an operation like this and have it go in a different direction.”

For one, the Anons involved in the Parsons case have not publicized the names of the accused rapists. “We’re not trying to inflict any punishment,” Fawkes says. “We just want the police to do their job.” (On April 12, the Mounties reopened their investigation, saying that a person had come forward with new information.)

Fawkes believes that it was a lack of cybersleuthing skills, not a lack of interest, that led the police to quit pursuing the case in the first place. “The reason that this is necessary and will continue to be necessary is mainly because the police don’t know how to do that type of work,” he says. “There’s not going to be any justice available through law enforcement, so the public is going to turn to whomever it can.”

“It has evolved into something that I think is like Batman,” says comedian Roseanne Barr, who began publicizing the Steubenville rape in December at the urging of KnightSec. “Batman goes to City Hall and he challenges the people in charge to do the right thing, and then he flies away in his Batmobile. That’s kind of what they are. They’re just challenging the people in power to do the right thing.”

McGill University anthropologist Gabriella Coleman, a leading expert on Anonymous, argues that the group’s impact has less to do with its hacking or crime-fighting chops than its evolution into a broad-based, PR-savvy group of activists and citizen journalists. “One of the elements that they exploit is the fact that there is all this data and information out there,” she says. “So who is willing to find it and package it in a compelling way? That is what they are good at.”

“We didn’t have to do it as Anonymous,” Fawkes admits, “but because we did, we were able to stir up so much support. We didn’t use Anonymous to commit a crime and then hide our identity; we used it as a tool to cause a media and internet uproar.”

So will going after rapists become a staple for Anonymous? After all, as Coleman told me, “It’s often accidental as to why they turn their attention to one thing versus another.”

But the activists behind #OPRollRedRoll and #OpJustice4Rehteah say they envision new Anonymous subgroups that would tackle multiple rape cases at the same time. There’s also talk of launching coordinated anti-rape protests in multiple cities, Occupy Wall Street-style.

“I think there’s going to be a lot more of this happening,” Fawkes says. “How can you say no? If this mom comes to you and says, ‘My kid was raped and the police won’t help me and I know who did it,’ what are you supposed to do?”