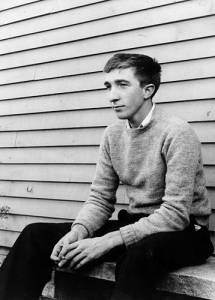

The biography at the end of John Updike’s novels was always the same:

The biography at the end of John Updike’s novels was always the same:

John Updike was born in 1932, in Shillington, Pennsylvania. He graduated from Harvard College in 1954, and spent a year in Oxford, England, at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art. From 1955 to 1957 he was a member of the staff of the New Yorker….

Then his life story stops, in 1957, landing him in the Merrimack Valley region of Massachusetts.

And there he remained, for the rest of his life, raising his four children, becoming a New England gentleman even as he unflinchingly exposed the sins and hypocrisies, particularly with regard to adultery, of the American success story.

Updike, 76, died yesterday of lung cancer. An incredibly prolific author, like other fruitful writers he faced mixed reviews and the lingering suggestion that his writing served a sort of masturbatory function. Like Philip Roth or Gore Vidal, his readers came to suspect that—with more than more than 50 books—there was nothing else much to learn. “Has the son of a bitch ever had one unpublished thought?” David Foster Wallace wrote, somewhat uncharitably, in a review of Updike’s Toward the End of Time.

Updike’s works included several series (the Rabbit Angstrom and Henry Bech novels), A Month of Sundays, about the midlife crisis of an Episcopal priest, Terrorist, about an American kid attracted to Al Qaeda (sort of a John Walker Lindh of working-class New Jersey), several short stories , and numerous books about adultery among the prosperous couples of suburban Massachusetts.

“Sex is like money; only too much is enough,” said Piet Hanema, the protagonist in Couples, the 1968 novel that made Updike rich and put him on the cover of Time. This obvious, and somehow unsatisfying kind of realization, appeared often in Updike’s work. Those weird insecurities, characters uncomfortable with their own lives, occurred over and over in his fiction. Updike was forever surprised and sort of fascinated that he was not still stuck in Pennsylvania, the son of a retail clerk with literary aspirations. Having reached the pinnacle of his profession early on, Updike was keenly aware that the neat, ironed out existence of haute-bourgeoisie America, of the two martini lunch and unacknowledged adultery, was often shallow and unsatisfying.

Unlike the characters of John Cheever, a writer to whom he was often compared—who quietly and tastefully go insane—Updike’s protagonists just muddle through. Miserable in their jobs, worried about their children, unhappy with their wives, they serve as telling and honest commentary on the discomfort many Americans felt about their own accomplishments.

Because so many of Updike’s characters represented Nixon’s “silent majority”—white, conservative, vaguely resentful of political change—Updike was sometimes called a racist, a misogynist, and a defender of the status quo.

All of this, while possibly true, entirely misses the point. Throughout his life Updike was a committed, though not particularly outspoken, supporter of progressive causes. The fact that his characters were often old-fashioned and bigoted is to his credit. It is not, after all, the duty of a writer to show the world as it ought to be; it is to paint a compelling picture of the world as it exists and the people who inhabit it.

He was not a writer of my generation. The sort of world he observed—of Oldsmobiles and after-dinner cigarettes, of post-war success and geriatrics—is not one I inhabit. But those things always seemed to me like mere details. An incredible researcher, Updike created a diverse cast of characters: painters, preachers, computer scientists, writers, dentists, actors, building contractors—the whole gamut of 20th century American professional success. But what he managed to do for all of this characters was demonstrate that everyone had AN inner life. He created a world, over and over, in which the mundane was made complicated and compelling.

With the death of John Updike America has lost a selfish, prejudiced, and astoundingly talented man, the sort of person who could see through the barriers Americans put up and tell readers what was truly going on.

—Daniel Luzer

Image by flickr user John McNab